While they’re not planning world domination yet, autonomous ocean gliders are helping oceanographers study Australia’s oceans.

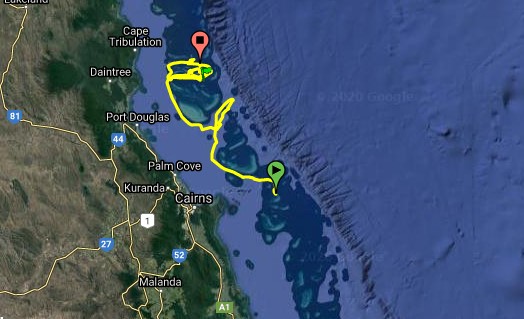

The gliders can go on their own weeks-long journeys far from shore, saving oceanographers thousands of hours and letting them explore waters too dangerous for human study.

Surfing a storm

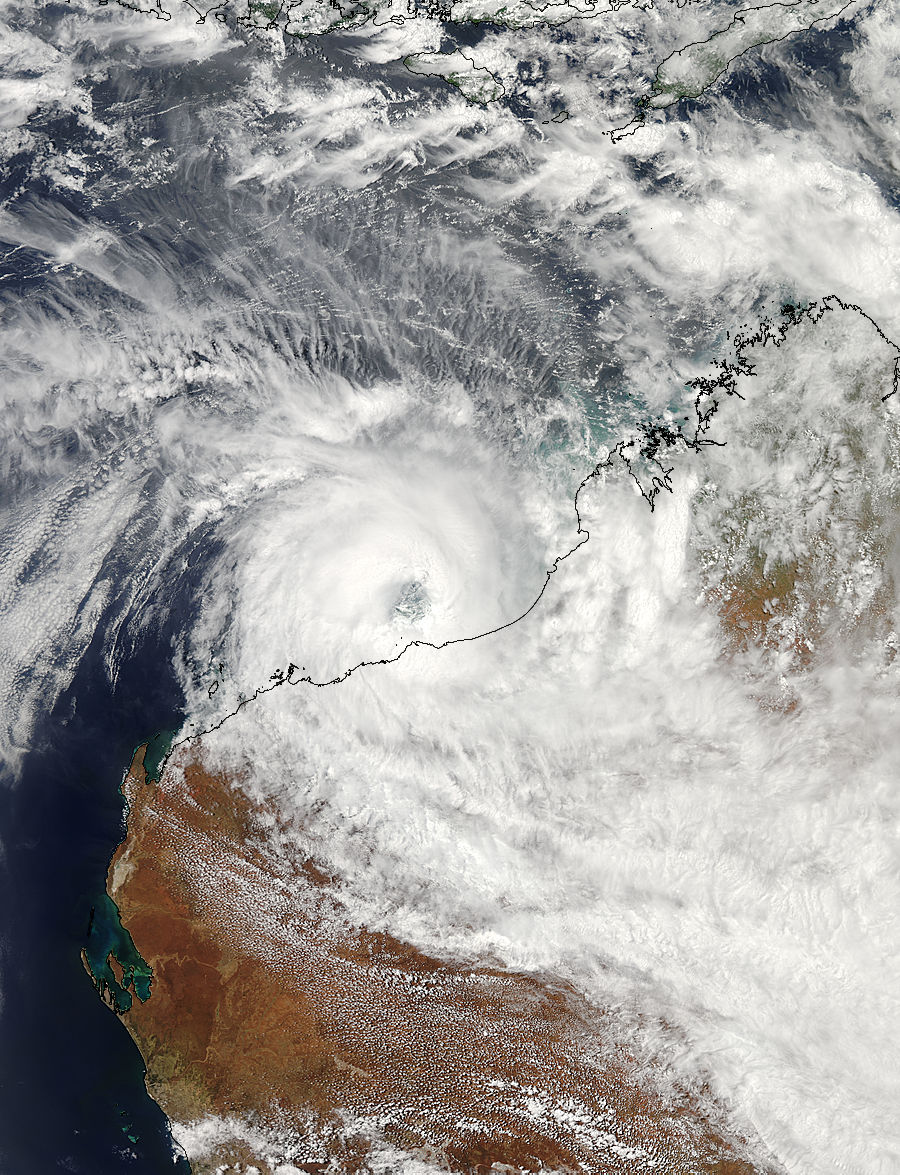

In 2013, one ocean glider was able to study the waters while caught in a tropical cyclone.

Professor Charitha Pattiaratchi is an oceanographer and facility leader at Australia’s Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS).

It was an IMOS glider that swam the cyclone’s depths. There, it took measurements of the raging currents on the ocean floor stirred up by Tropical Cyclone Rusty.

In the midst of that cyclone, the glider showed Charitha’s team how algae gorged themselves on the nutrients stirred up from the ocean floor to create an algal bloom the size of Tasmania.

Saw-tooth bats of the sea

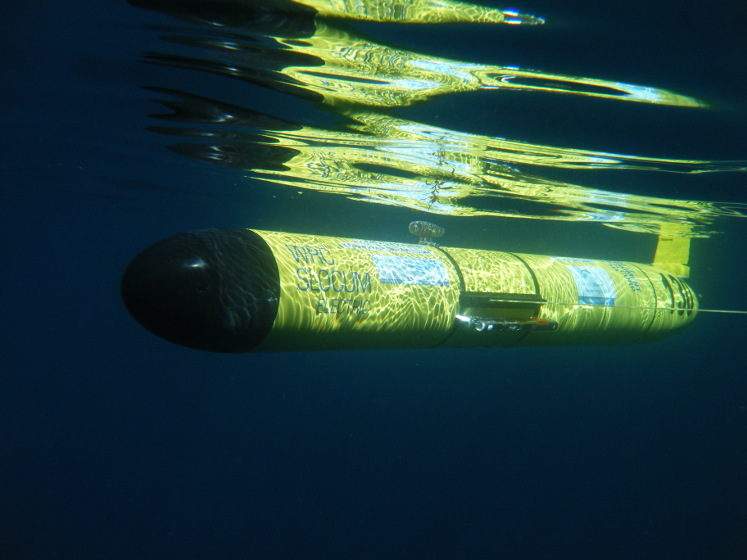

Ocean gliders are autonomous devices. This means they’re able to sense their environment and navigate around without human input. The key to their autonomy is in their nose.

“They have an echo-sounder on their front. That makes sure they don’t knock anything on the seabed,” Charitha says.

The echo-sounder makes a chirp and then records the time until it hears an echo. This lets the ocean glider sense obstacles in its path and detect the seabed.

To move around, they use a buoyancy engine. The engine moves a piston to change the glider’s volume and move it forward.

This lets the glider stay out for weeks at time. One journey from Australia to Sri Lanka lasted 11 months.

As the glider saw-tooths through the water, an onboard science lab lets it take measurements.

“We take temperature, salinity and water density readings. We then test chlorophyll so we can tell how they’re all related,” Charitha says.

Chlorophyll is the bottom of the ocean food chain, so measuring it shows how sea life is adapting.

The invisible toxic tide

Charitha’s team were also able to discover something unique about Australia’s coastline.

Australia’s coastal waters are cold in winter. Cold water is denser, so it sinks to the bottom of the ocean as it drifts out to sea.

When the water sinks, it brings with it sediment and pollution from rivers, transporting it huge distances, and invisible to us until now.

“In the northern hemisphere, pollution and sediment from the rivers is carried out on top of the sea. You can monitor that using satellites. In Australia, it’s the opposite,” Charitha says.

“The carbon and pollutants we introduce at the coast are sent out to sea on the denser water.”

It’s a discovery that shows two key things. Australia’s impact on the ocean is much larger than we initially thought, and there’s a world of hidden pollution we still know very little about.