Earth is a blue planet. Water covers more than 70% of its surface.

At its deepest, you could submerge Mount Everest in it and still have kilometres to spare.

So when we talk about plastic ending up ‘in the ocean’, that’s not as helpful as it sounds.

TRASH TALK

Mirjam van der Mheen is a PhD candidate with UWA’s Oceans Institute. She’s on a mission to find out where our ocean-bound plastics end up – which is trickier than you’d think.

“It’s not possible to measure plastics remotely using satellites or anything like that,” Mirjam says.

“People have to actually go out, throw a net in the ocean, drag it through the water and count how much plastic they caught.”

“That’s a very time-consuming process and the ocean's very big so it’s ... hard to do that."

A BIT OF A DRIFTER

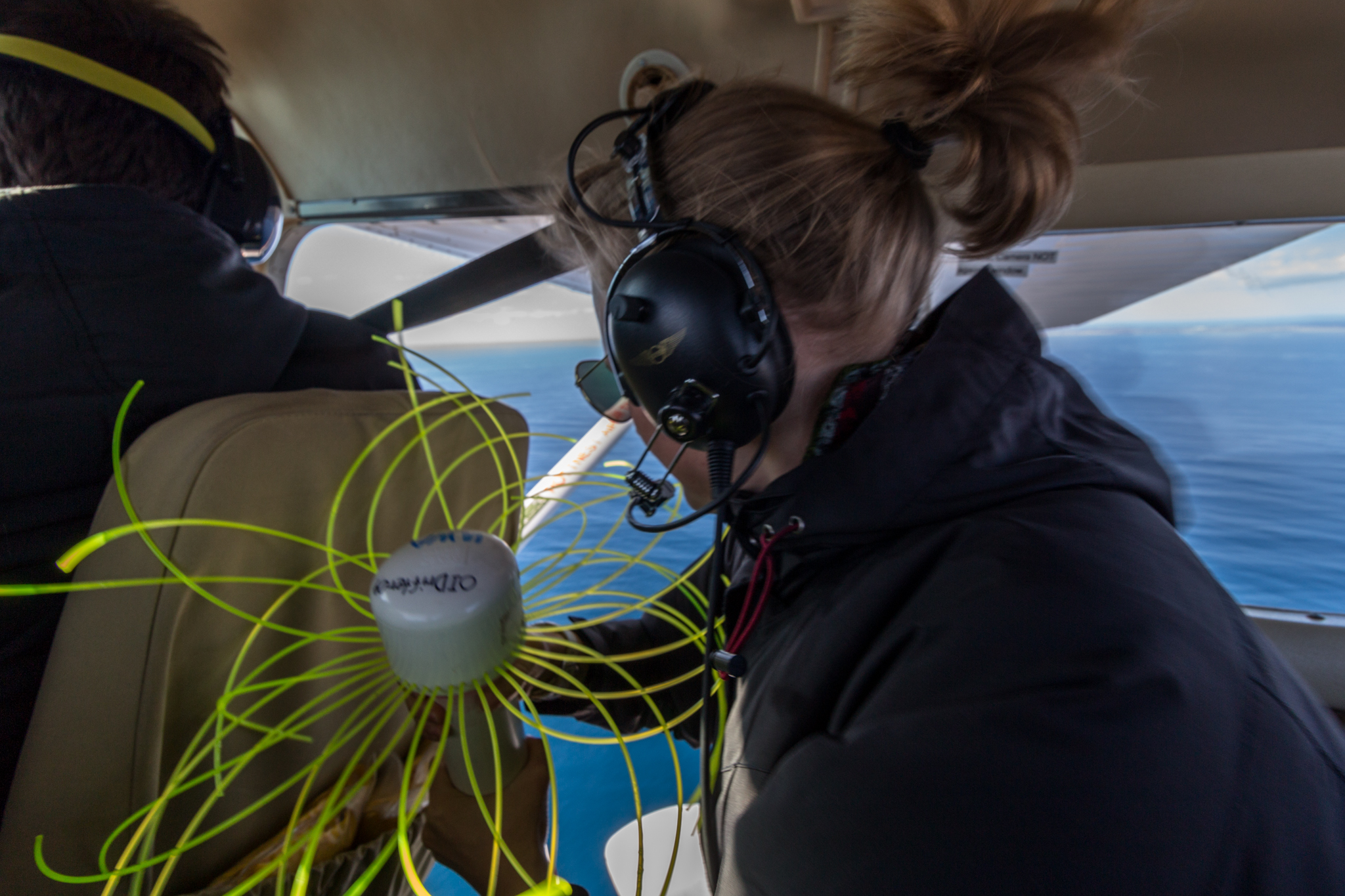

Instead of sifting entire oceans to determine their plastic content, Mirjam works with things she can track – ocean drifters.

“Essentially, they’re just floating buoys with a GPS tracker inside them,” she says.

A network of these buoys float around the world, with data from ocean drifters dating back to 1979.

“You can see how things move in the ocean because now there are actual things out there floating around,” Mirjam says.

The main programs are run out of the US and Europe, which means the Pacific and Atlantic are well-studied. But there’s a bit of a gap in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of WA.

Mirjam’s been experimenting with building her own drifters and testing them out near Rottnest.

“They can be whatever design you want as long as it floats,” she says.

“I ended up using a cylinder of PVC tube and then got a commercial GPS tracker – the kind you usually stick on your very expensive boat or truck so you know where it is.”

A MODEL CITIZEN

Once you have an idea of how the oceans are moving, you can predict where plastic might end up.

“Using computer models we can have a pretty good idea of what the ocean currents are doing at any given time,” Mirjam says.

Much like a weather forecast predicts wind direction, these models simulate the speed and direction of ocean currents.

“I can release virtual particles in those ocean currents and if you know how fast those currents are going, you can calculate where those particles end up,” she says.

THAT FLOATING FEELING

But ocean currents alone don’t give a complete answer.

“The tricky thing with plastic is that it’s a term for a lot of different types of materials,” Mirjam says.

Different types of plastic have different densities. While about 65% of those float, the rest sink.

“Depending on how floaty something is and how high it sits in the water, it’ll behave differently because the wind and waves are acting on it too.”

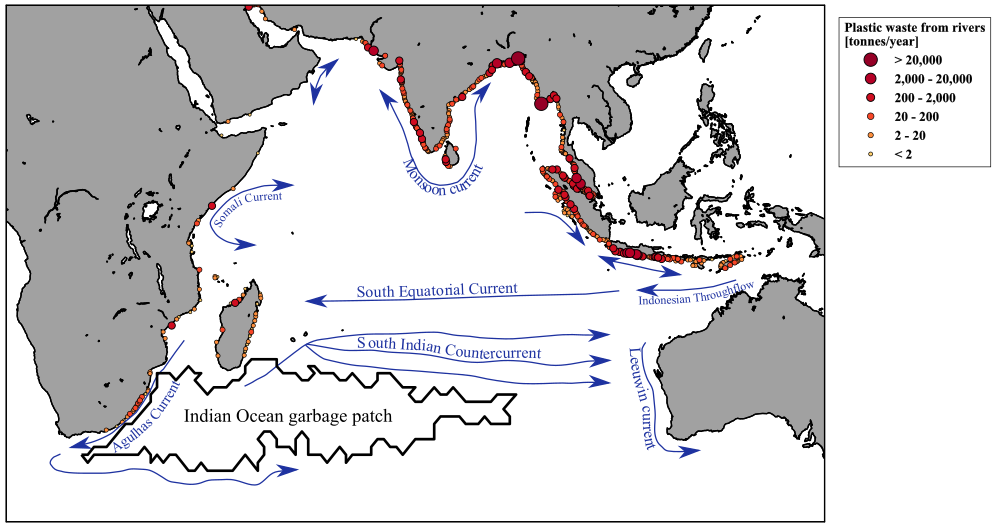

“If you only look at what ocean currents are doing, the garbage patch in the Indian Ocean behaves very differently.”

So as well as currents, predictions about plastic should include wind and waves too.

GARBAGE PATCHWORK

The models suggest there are two garbage patches in the Indian Ocean – and they’re more complex than their Pacific and Atlantic cousins.

One seems to sit to the south, just off the coast of Africa – but it’s not a single neat spot.

“As soon as you add wind and waves, the garbage patch becomes very leaky and it empties into the South Atlantic Ocean,” says Mirjam.

The other is in the north and is more of a stream, moving back and forth around the point of India with the Monsoons.

Worryingly, plastic doesn’t just stay out at sea – it washes back up on coastlines, which are home to much more marine life.

Thanks to the Leeuwin current though, WA’s coastline remains relatively plastic-free.

“It’s essentially like a highway – if you end up in there, it’s easy to go along with it but it's pretty hard to cross it,” Mirjam says.

TAKING THE Rubbish OUT

If that all sounds a bit grim, it’s worth remembering that understanding the problem is the first step to solving it.

“That hopefully will be my next research project,” Mirjam says.

“Map(ping) of all the beaches that are most affected and where it will have the highest impact, so that will help prioritise beach cleanups.”

That map could tell us where waste comes from, which would help prevent plastics entering our oceans in the first place.

“Which, I mean, ideally we would do everywhere, but this would give us a place to start.”