It’s dominated by lush, golden-green forests, which sometimes run all the way up to the beach. It’s dotted with craggy caves and the occasional grassy meadow. It’s filled with more endemic species than any other ecosystem like it in the country.

Also, it’s entirely underwater.

This is the just a tiny corner of the Great Southern Reef, and it’s the southwest forest you’ve never heard of.

Wait, what?

The Great Southern Reef (or GSR to its friends) actually reaches far beyond the southwest. In fact, it stretches along most of Australia’s southern coastline, according to one of those friends, UWA Oceans PhD candidate and benthic ecologist Sahira Bell.

“These kelp forests are the defining feature of the Great Southern Reef. It’s this massive, interconnected system that goes all the way from Kalbarri on the west coast, south around the whole south coast, around Tassie, up the east coast and all the way up to northern New South Wales.

“Really, it’s the southern half of the continent.”

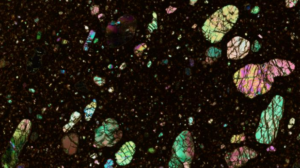

Sahira studies the kelp – or seaweed, or macroalgae if you want to get technical – which makes up the foundation of this ecosystem. Kelp fills the same ecological niche as the trees in a land-bound forest.

“It’s a habitat provider,” she says. “It provides the food, the shelter, the structure for that ecosystem and for everything to live within it. It really is the foundation species.”

And according to Sahira, once you’re beneath the surface, it feels like a forest too.

“It’s not just a big flat rock with some fluffy stuff going around it. We get these big boulders and big crevices, and it really does feel like you’re swimming through these tunnels in a forest area,” she says.

“I think there’s something really beautiful about that mix of these seaweeds providing a forest-like structure and then your sponges providing these alien-like structures. And then you mix in all these corals and fish and invertebrates everywhere.

“It is an absolutely beautiful environment to work in.”

Much like the pockets of trees that link habitats in our cities, Sahira says, it’s the kelp forests that knit the otherwise disconnected rocky reefs along the southern half of the continent into one, single, enormous ecosystem.

“We think of the Great Barrier Reef as a place, even though it’s not actually one single reef – it’s this series of interconnected reefs,” Sahira says.

“The Great Southern Reef is exactly the same. It’s a series of connected places. And these connected places are defined by the kelp forests.

“Even though it’s not a physical rock connecting them, they are still sharing that ecological connectivity.”

We’re having a heatwave …

So far, Sahira’s research has focused mostly on the northern parts of the Great Southern Reef. While the cooler south and southwest are mostly pristine, the warmer parts of the reef are among the first to feel the impacts of climate change.

A marine heatwave in 2011 wiped out kelp forests along about 100km of coastline near Kalbarri. The loss of these forests was devastating, and impacts ricocheted through the ecosystem. Even now, almost 10 years later, most of these pockets still haven’t recovered.

“We saw these flow-on effects all the way through the ecosystem. We saw big changes to the fish communities there. We saw massive losses in our abalone and our rock lobster,” says Sahira.

But some parts, incredibly, seem to have survived.

“During my research out there, we literally stumbled across kelp forests that we didn’t know existed. These seem to be healthy populations that we’re now finding out may have been resilient and survived the heatwave,” she says

"There is something about these populations of kelps. What’s their secret that they survived?

If they can crack it, Sahira’s colleagues are also experimenting with ‘reforesting’ patches of reef with new kelp. While seagrass puts down roots in sandy ocean floors, baby kelp need a solid surface to anchor to. The solution could be spreading ‘green gravel’ – small pebbles with resilient strains of kelp already starting to grow – but that can only work if the team have healthy kelps to seed the pebbles with.

Southern water tribe to the rescue

So far, Sahira’s research has focused mostly on the northern parts of the Great Southern Reef. The pristine southern part of the reef could hold the clues to help its northern end survive – but Sahira says what’s down there is pretty much a mystery.

“We have lots of modelling that suggests the region east of Esperance could be absolutely stunning and potentially quite resilient to future change,” Sahira says.

“But it’s still astounding to me that I could not tell you what is in that region. We just do not know. We could have a guess about what’s around here based on what’s found on the other side. But there is no research to accurately say.”

While it’s (comparatively) easy to study the northern forests, it’s much harder to study their southern counterparts.

Part of that, Sahira says, is due to funding. It’s easier to get grants to study areas that are clearly at risk than to look closer at areas that are seen as healthy.

But mostly it’s because those pristine forests are just straight up hard to get to.

“It’s quite wild, especially when you get down on the south coast. And it’s super remote.

“I think that’s the key component which is stopping any research getting done. It is difficult for us to get down there and expensive for us to get down there.”

At least it is if you want to study them. If you just want a day trip, Sahira says you can get a pretty good look at what the GSR is all about just by taking a snorkel off South Cottesloe.

“It’s the northern end of the dog beach. I didn’t even know it existed until I helped with an undergrad unit and we surveyed that area.

“You can snorkel out from the beach. And once you get past the little sandy patches, you start to see all this beautiful structure, these big boulders and crevices – and the seaweed life there is beautiful.”

It’s well worth a look – not just because it’s closer to home, but because it’s just as critical as its more famous cousin.