According to PhD student William Thomas, we need to understand another creeping threat to plants: a lack of genetic diversity.

At UWA’s School of Biological Sciences, William looks at innovative ways to manage the recovery of plant species threatened by population decline.

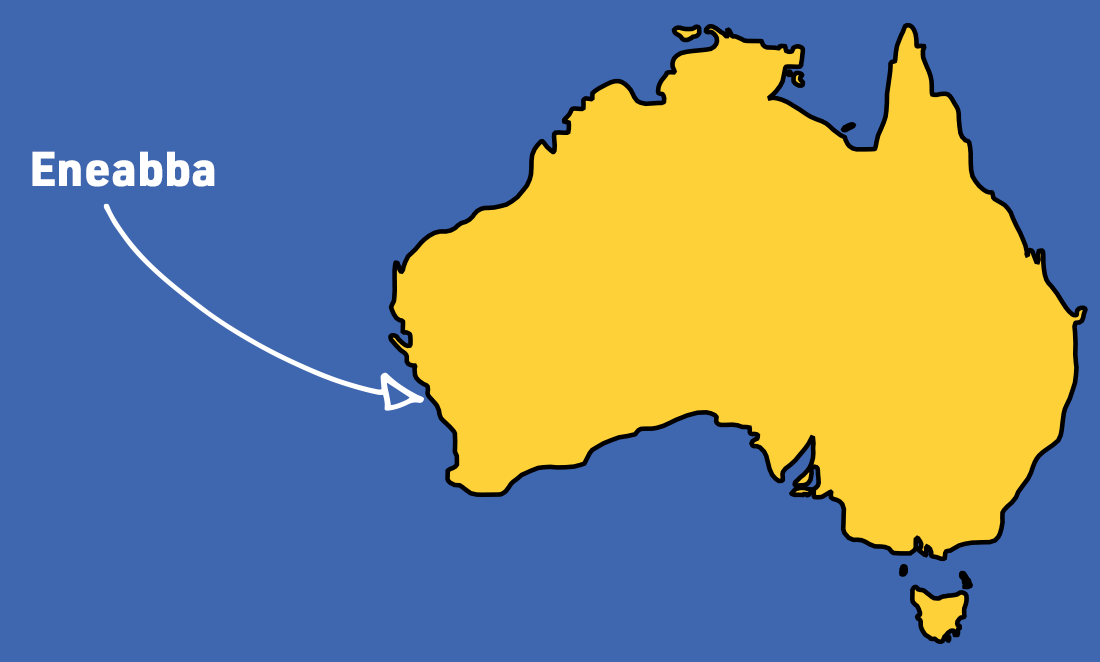

In this study, William and his team focused on Styphelia longissima (Ericaceae). It’s a critically endangered shrub, restricted to a single fragmented population near Eneabba, 250km north of Perth.

But S. longissima isn’t threatened because of introduced species or fires. Its small population and isolation mean it could become threatened by a lack of genetic diversity.

Genetic diversity

So what’s the first step in understanding the importance of genetic diversity for the long-term survival of a species? Finding out where plants come from. We don’t normally think of plants as having parents, but they do.

“Flowering plants mate sexually, just like humans and animals, but through pollination,” says William. “The pollen moves from the male part of a flower to the female part of another flower.”

Scientists even have plant paternity tests. These involve collecting samples, extracting the DNA in the lab and then predicting which parent is most likely to be correct for each seedling, based on genetic data.

If a species has low numbers, it becomes very important which flowers mate, just as it is with humans. Take Iceland for example. The country’s total population is only a little over 350,000 people. As a result, they have an app that helps citizens avoid dating their own relatives.

“The more genetic diversity in a species, the more likely a species can adapt to changing environmental conditions,” says William.

“Genetic diversity gives you an evolutionary advantage through flexibility.”

Even though the population of S. longissima is small, the species currently has reasonably high genetic diversity. According to William, this is probably because the surrounding land was recently cleared.

“The remaining population is reflecting those higher levels of genetic diversity that were present before land clearing.”

“But from our study, we found lots of inbreeding and other factors that will cause a decrease of genetic diversity over time. So the population of S. longissima should be carefully monitored.”

This means the shrubs will become more vulnerable to environmental changes over time.

It’s a good thing the environment isn’t changing … right?

“The climate is changing so rapidly that the plants can’t keep up – especially those with reduced genetic diversity.”

This is particularly true in extreme Western Australia, where many species are already living on the fringes of survival.

But according to William, there are steps that can be taken to fix the problem.

“A good first step is conserving the populations that are left in case things get worse. We collect seeds and store them off site in case the remaining population is compromised.”

Indeed, the technique of storing seeds has been embraced by countries around the world with the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. This has even seen countries like North Korea contributing thousands of agricultural samples. And Australian native species are being housed in the Millennium Seed Bank in London, thanks to a partnership between Kings Park Botanic Gardens and Parks Authority and Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

“There are also ways to mitigate inbreeding, like manually pollinating plants in other genetically different areas.”

“But the best way is translocation. This involves moving plants to a new location with the hope that they will grow, reproduce and be self-sustaining, but with a higher level of genetic diversity and ability to adapt to changing conditions.”

Translocation isn’t easy and can take years. Imagine if you had to set up a colony on Mars. Once you get there, you’ll face a whole load of new challenges – potentially very different to what your Earth-bound mates are facing. That’s why William hopes genetic diversity will be better understood by state governments and bodies responsible for conservation.

“Although it is still underutilised, our understanding of genetic diversity has been slowly growing over a number of years as a key concern when thinking about the conservation of a species.”