Designing an electric racing car is a very different challenge to designing, say, an electric postie bike. But with student racing events cancelled for the year, the ECU motorsport team found themselves with plenty of time to get started.

“We’re concerned a lot more about short term performance than maximum efficiency,” says technical director Adam Honeycombe.

“Our job is to get one guy around a track as quick as possible.”

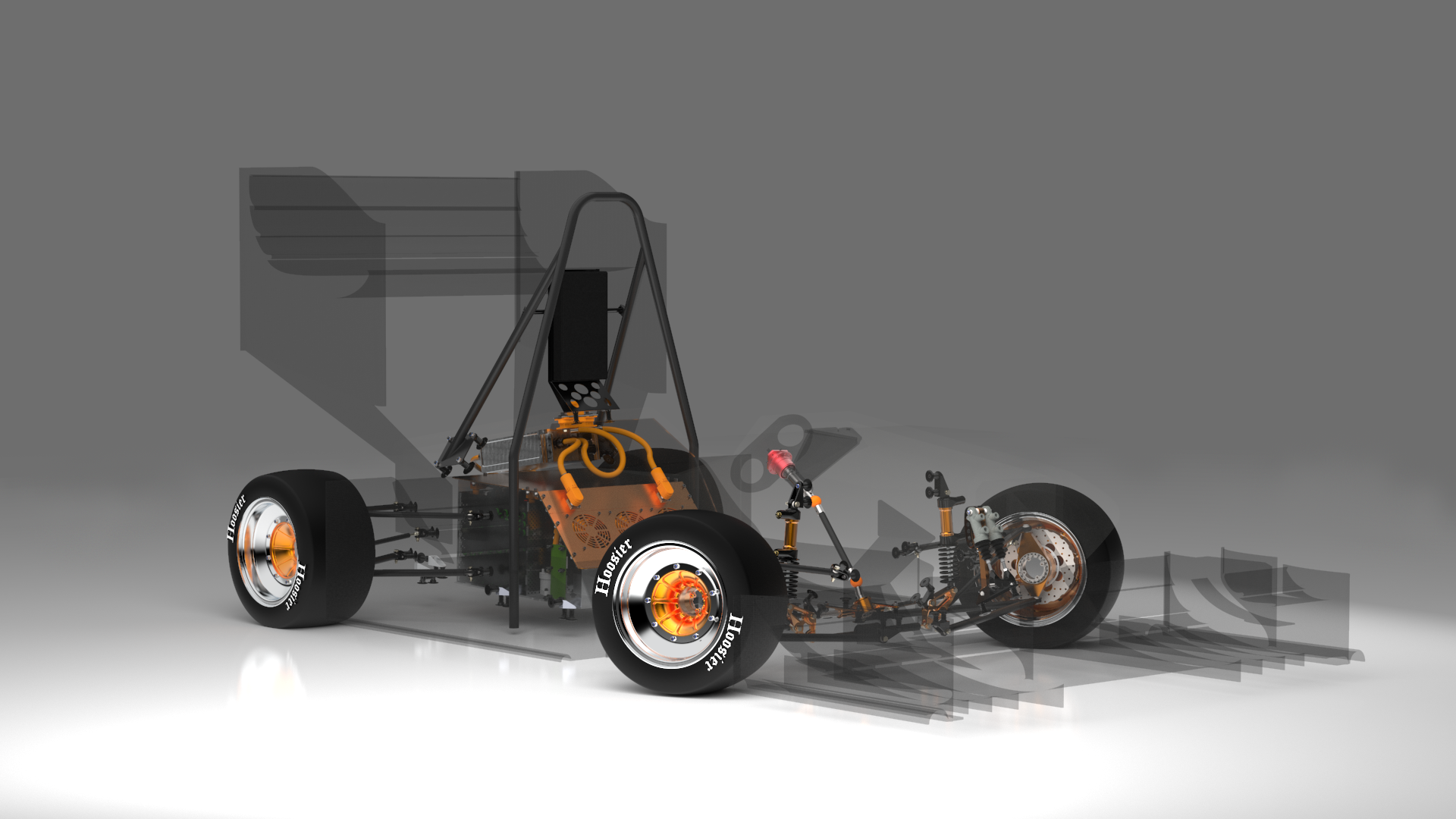

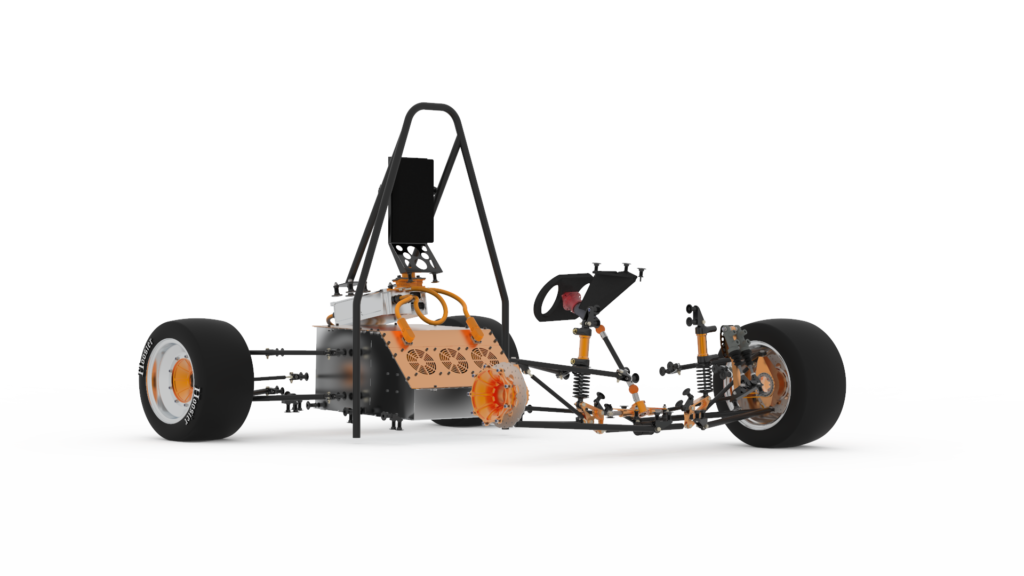

Electric motors and batteries are more-or-less available off the shelf. The hard part of building a racing car is making everything work together – and, obviously, making it fast. That ends up being a pretty tricky engineering problem.

“You’ve got to check everything against everything. All the systems have to be integrated,” says Tom Mayes, who’s been designing the car’s electrical system.

That means a small change – like slightly heavier suspension, for example, has knock-on effects through the whole car.

“If you’ve got heavier suspension, your car weighs more, so you need a more powerful motor. Then you need more batteries. You might actually need to jump up to a different voltage like range for your battery pack. So it ends up a different shape, so your car ends up a different shape, which changes the aerodynamics, and so on.”

TOrque about a challenge …

All this design work has to be finished before anything starts being built. Where an internal combustion car, the team says, can be built and then fine-tuned, an electric vehicle has to work together from the start.

“There’s nothing to tune. It’s just about throwing more electrons at the copper so it makes more power,” says Tom.

Working with a battery also makes the design harder to test once it’s complete. The team might spend all day testing an internal combustion car, refuelling between tests. An electric car gets one run day, and then needs to be recharged overnight.

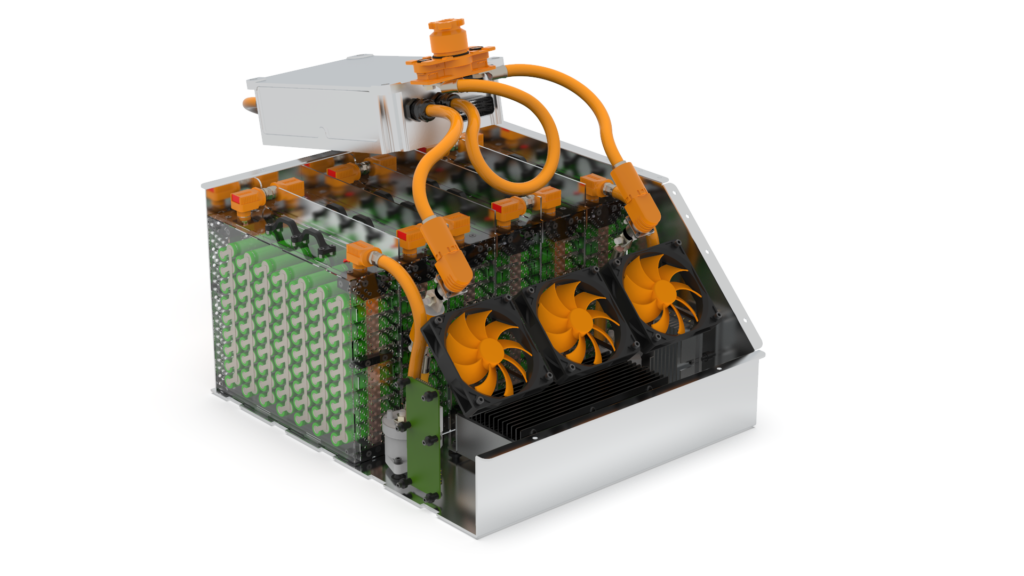

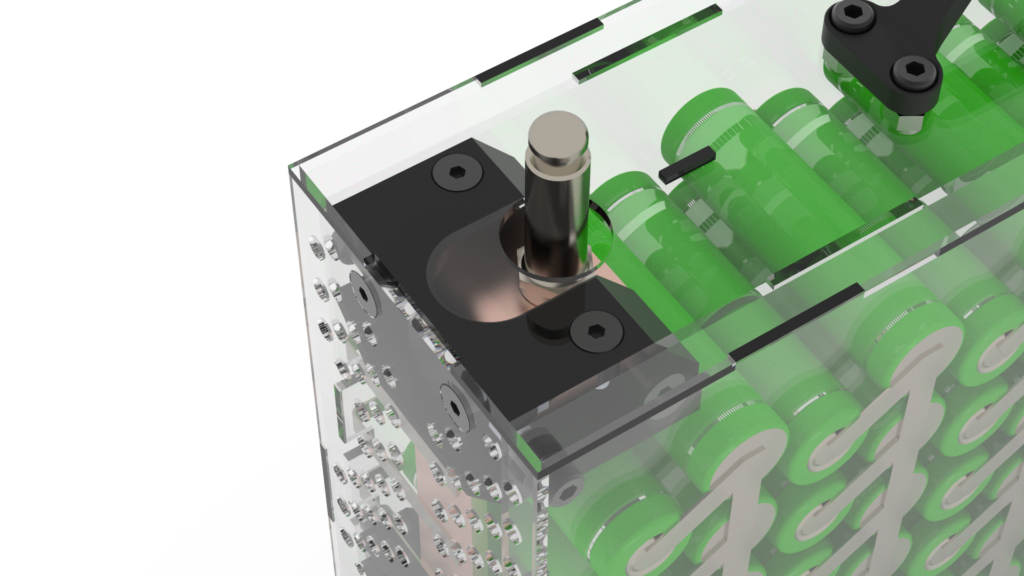

Cells like victory

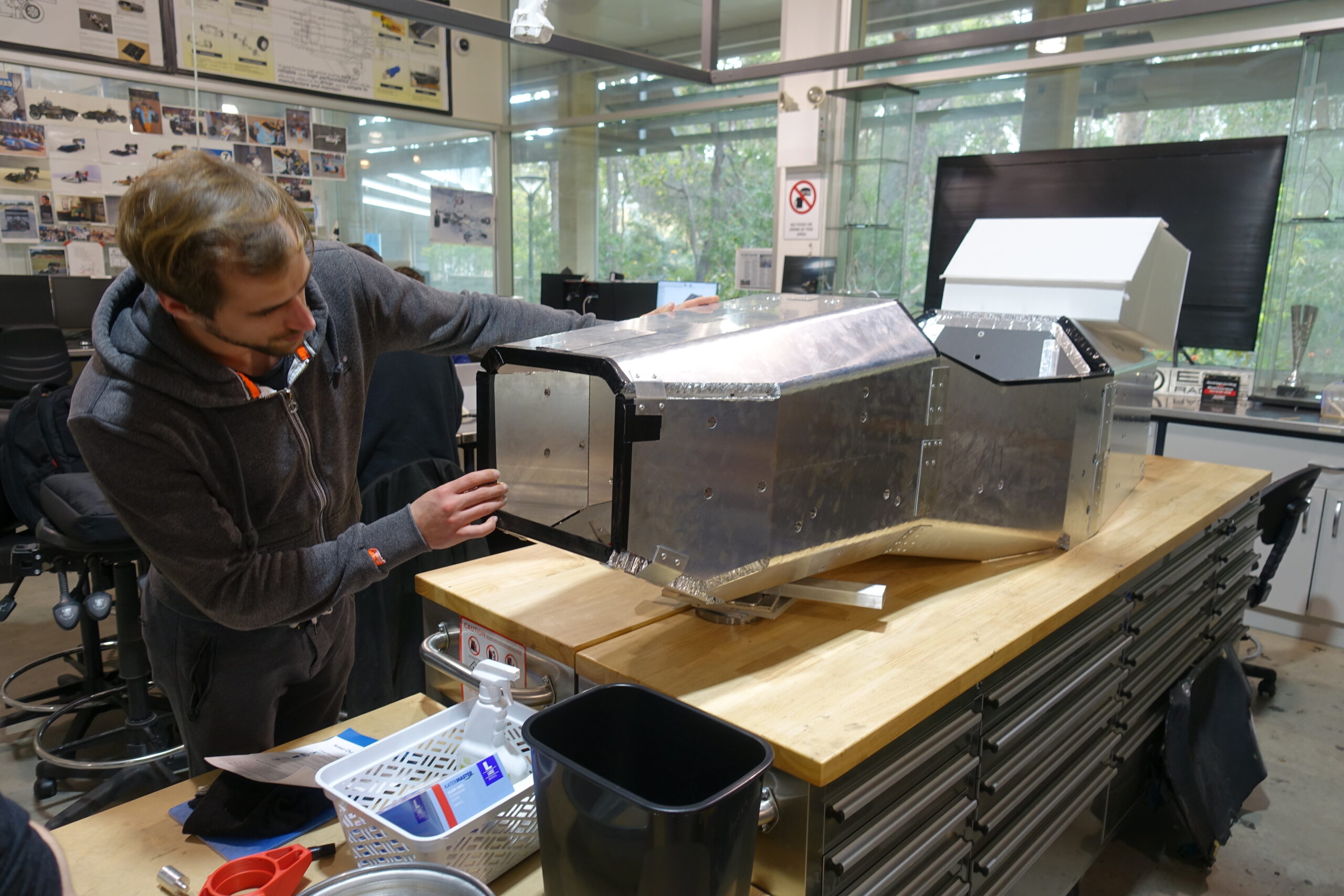

The team is currently working on their battery, custom assembled from the same sized 18mm x 65mm lithium cells you’d find in an old-school laptop – or the underside of a Tesla.

“We’ve got 756 cells, which sounds like a lot, but it’s not really that much,” says Tom.

(For comparison, a Tesla has over 7000.)

“The motor that we’re using in this car is smaller than one of the wheels by quite a long way. And it puts out more power than our old internal combustion engine. But the whole system is heavier and bigger because of the batteries,” says Tom.

“The whole engine from the last car is as big as the battery in this one,” adds Adam.

While the front of the car looks pretty much the same, these changes have meant that everything behind the seat will look completely different – so much so that the first thing they’re checking is whether everything will actually fit.

It’ll be completely different to race as well.

“Your right foot has a connection to the rear wheel at the speed of electrons,” says Adam. “It’s not quite the speed of light, but it’s pretty damn quick.”

“That’s going to be really cool to feel.”