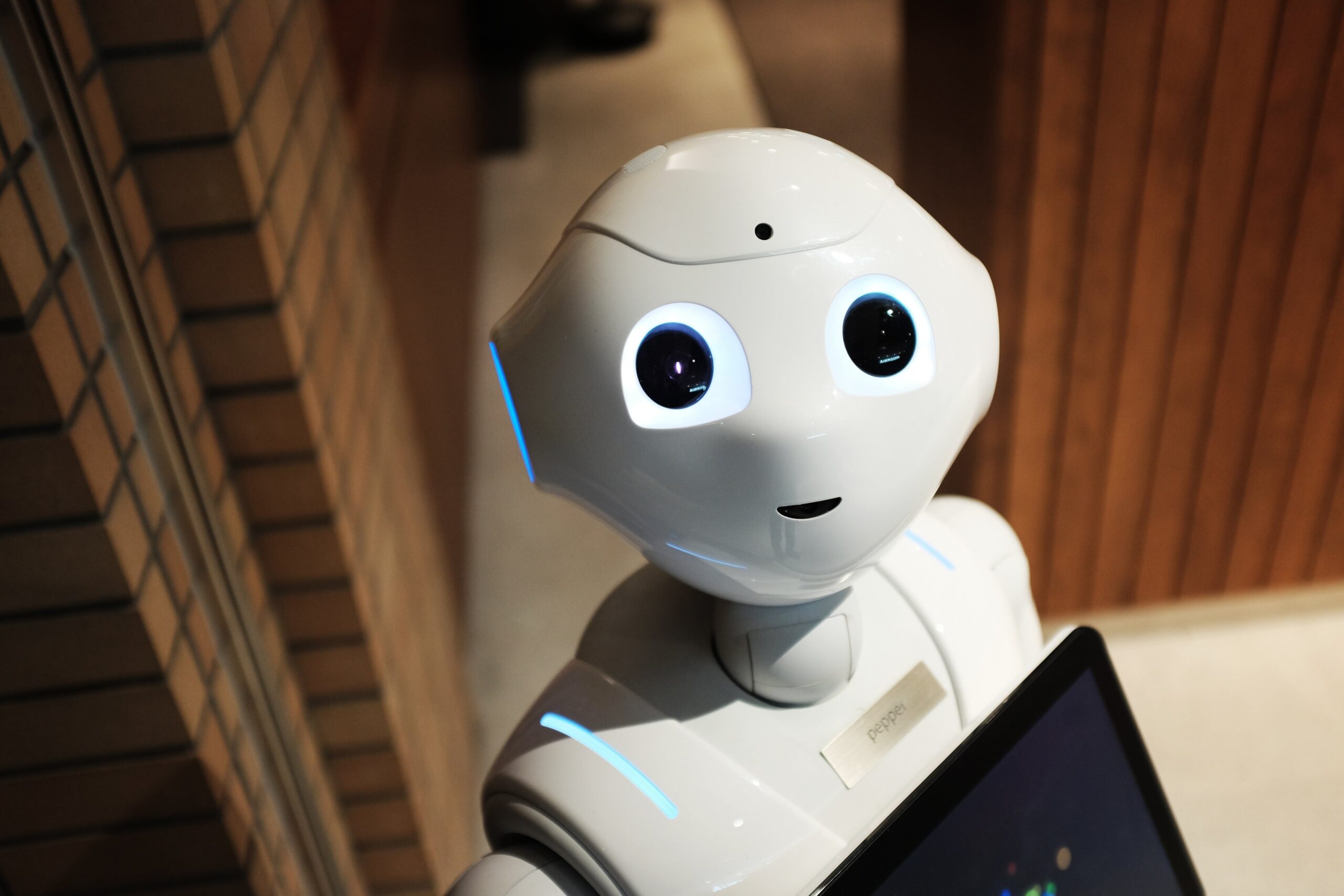

You sound sad today. Shall I call someone for you?

It’s the kind of question a future companion robot might ask someone who lives alone.

Professor Dave Parry, Dean of IT at Murdoch University, is leading us towards this possible future.

His work focuses on how machine learning could detect emotion by analysing a person’s speech.

“Humans can tell other people’s emotions by the sound of their voice,” Dave says.

“In machine learning, the general principle is that, if humans can do it, there must be the data there that a machine could possibly do it.”

The research isn’t studying the actual words we use but how we say them.

“[It’s] the tone and frequency of the words, how split up the words are, how often you can manage quite complex, repetitive sounds and things like this,” Dave says.

“You can put all of those into a series of machine learning tools.

“And we’re pretty happy that we can generally identify emotions at a pretty high level of accuracy.”

HOW TO MAKE A PERSON FEEL

Most speech recognition programs have been trained using actors performing different emotions such as angry, sad or disgusted.

But Dave is interested in training machine learning algorithms on real emotions.

He’s fascinated by psychological experiments that induce certain feelings in participants.

For instance, you can induce disgust by getting participants to put their hands in a bucket of something that feels like worms.

“If you want to get people scared, you basically shock them,” Dave says.

“To make them angry, you give them tests, but you keep marking them wrong on the tests.”

Then there’s a universal way to induce laughter and happiness.

“You get a fart machine,” Dave says.

“Everybody in the world thinks farts are funny so you get a genuine laugh.”

FOR BETTER OR WORSE

Dave’s work uses speech recognition to support mental health, particularly for people suffering from depression.

But commercial companies could also develop similar technology and use it to target customers when they’re susceptible to a big purchase.

“There is absolutely, definitely a risk of that,” Dave says.

“You’re basically getting a fairly independent insight into somebody’s emotional state, which is really useful for advertising or marketing.”

However, Dave is focused on the potential benefits.

EMPOWERING PEOPLE

Dave says it’s exciting to offer people an assessment of their own emotional state so they can make informed decisions.

He says it can be hard to see when we’re approaching our own limits.

“People are very bad at that,” Dave says.

“Usually people go past [breaking point], and then they need to recover.”

“We can give information to people so they can go ‘I’m nearly there, but I’m not quite, I’ll change my behaviour now’.

“That’s, I think, something that’s really, really powerful.”

Dave points to researchers in the US who designed a tool for a colleague with bipolar disorder.

“He was able to detect, from his phone activity, when he was going towards a manic state,” he says.

“He could then up his medication … but also do things like stop access to his bank account and get somebody in to help him.

“Because he had about 12 hours warning of that happening.”

Dave says the tools can be very empowering for people and help avoid catastrophic outcomes.

“You learn yourself about what works and what doesn’t.”