When it comes to caring for space rocks, Associate Professor Gretchen Benedix is an expert.

A cosmic mineralogist at Curtin University, Gretchen says the first step is working out what she’s dealing with: A chunk of asteroid? A piece of planet?

After an educated guess based on external appearance, the next step is a CT scan.

“These scans give us a 3D look at the interior of the meteorite, without damaging the samples,” says Gretchen.

“This is extremely important, because meteorites are so rare, we want to be able to examine it before we cut into it.”

Gretchen’s team uses density data from the CT scan to decide which part of the meteorite to sample.

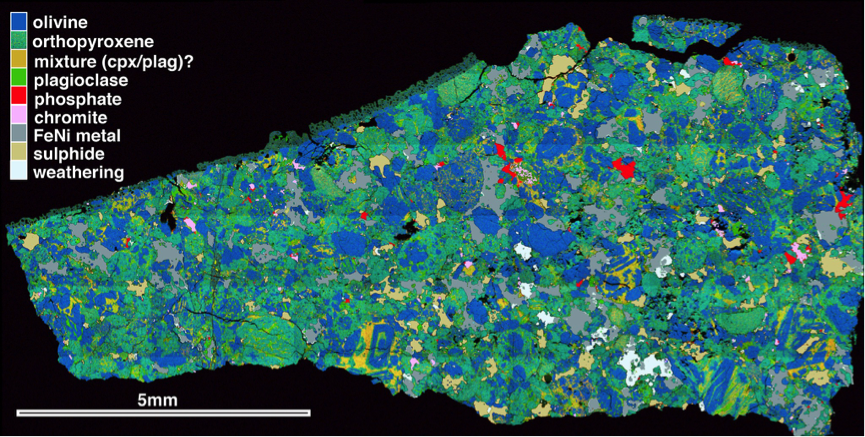

This chopped-off bit is then sectioned into “paper-thin slices”.

Each slice is analysed for its mineral composition using an electron microprobe.

Although many of the minerals in space also occur on Earth, it’s the ratio of elements in these minerals that helps identify them.

DNA for rocks

The types of oxygen present in a meteorite help us figure out what sort of asteroid or planet it came from.

While most oxygen atoms contain 16 neutrons, oxygen isotopes can contain 17, or even 18 neutrons.

“Isotopes of oxygen act like DNA for meteorites,” Gretchen says. “Every rock from the Earth has a specific oxygen isotopic signature.”

“We can tell a meteorite isn’t from Earth when its oxygen isotope composition is different.”

Hot and/or bothered?

The texture of a meteorite also tells a tale, allowing the team to estimate how hot the meteorite was on its parent body, and how much impact damage it may have sustained.

“We look at a variety of textural features using high-resolution CT scanning, or looking at the thin section down a regular microscope,” says Gretchen.

Relatively unmelted meteorites may have been that way since our solar system formed, 4.567 billion years ago.

Hunting for knowledge

Gretchen is passionate about meteorites—she’s twice been to Antarctica on meteorite-hunting missions—so she’s always super-excited to find a new one.

“In essence, they are ‘free sample returns’ from asteroids, or the Moon, or Mars,” she says.

“We can…tie [a meteorite’s] composition and texture to temperature and pressure conditions on an asteroid.”

Understanding these rare and randomly supplied “samples” helps us to better understand the way the solar system formed and evolved.