In the 1990s we weren’t worried about the end of the world as we knew it due to climate change or terrorism.

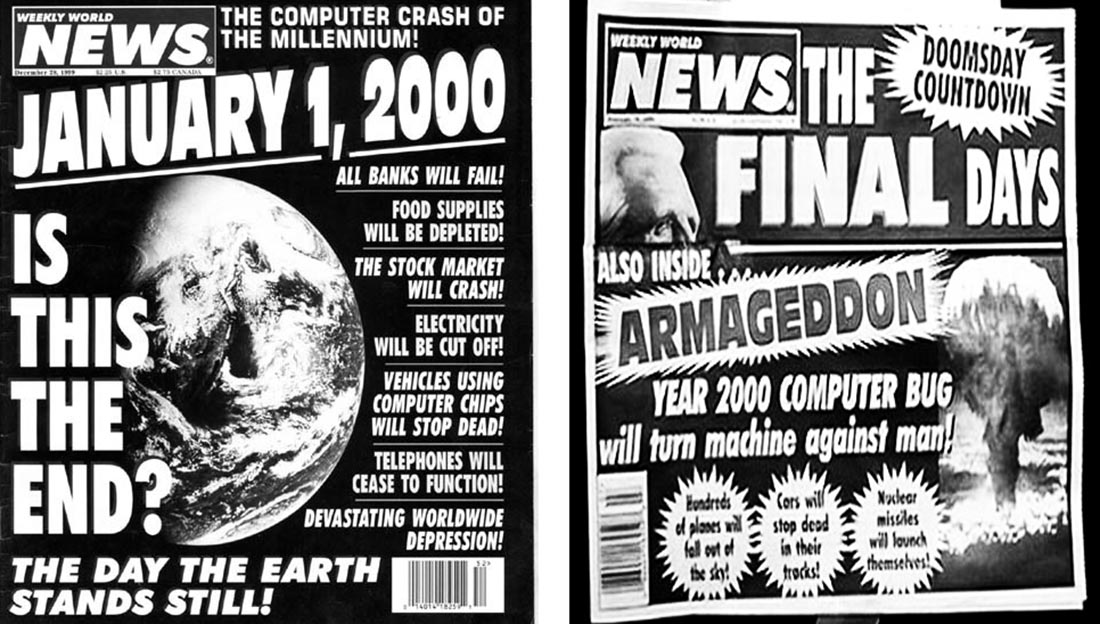

No, we were worried about the world ending as the clock ticked over from 1999 to 2000. The threat was a potential calendar glitch called the Y2K bug or the Year 2000 problem.

So what was it? Basically, the prospect of a few missing digits in a lot of old computers caused an end of the millennium panic.

Social media meltdown

Too young to remember Y2K? Dr. Richard Forno, Director of the UMBC Graduate Cybersecurity Program in the United States, has a modern day scenario for you.

“Imagine a world where nearly everyone thought Facebook, Twitter, Snap, Insta, TikTok, Google, Postmates, Deliveroo, Uber… wireless networks, power grids, … pretty much all aspects of modern life …. were predicted to all go down at the same time,” Richard says.

Insert face screaming in fear emoji here, right?

OMG it’s Y2K

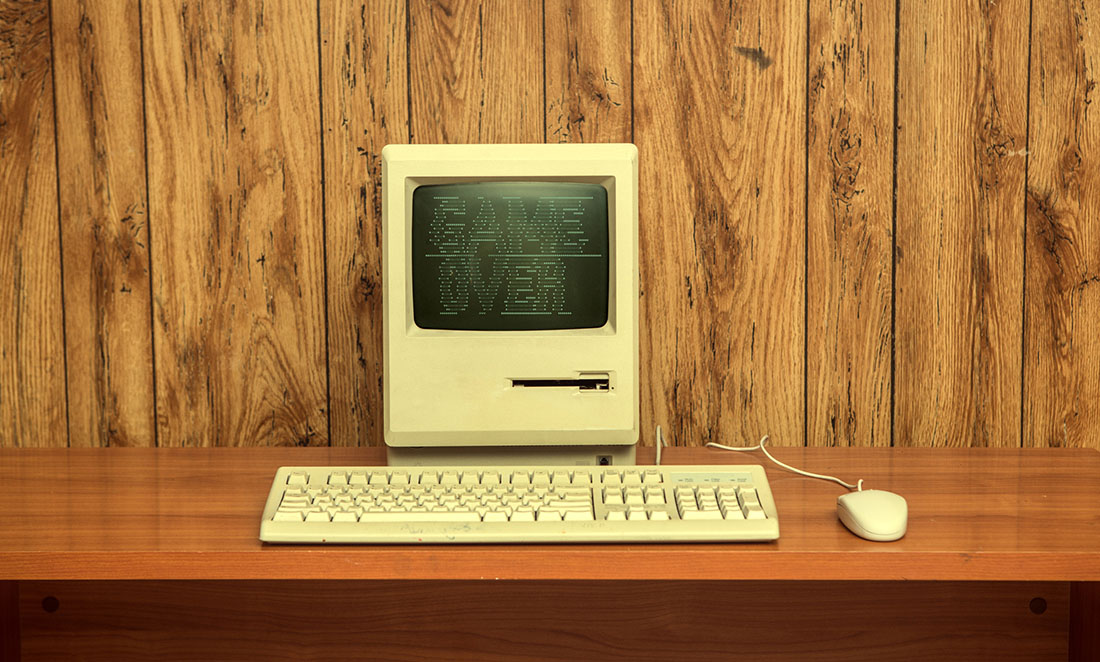

While computers today (and even 20 years ago) have lots of storage space, that wasn’t the case back in the 1960s.

Back then, space was so limited that early programmers took a shortcut to save space when making them.

While it may sound ridiculous today, they used a date format where the year was only two digits – such as 99 – instead of four – such as 1999. Yes, those two extra digits actually took up a relatively large amount of space on those ancient computers.

The problem was that no-one thought the computers and programs would still be in use 40 years later when 2000 rolled around.

Richard, who completed his PhD at Curtin University’s Internet Studies Program, says “the world was based, if not dependent, on all these systems. Nobody really thought about the ‘bad side’ of networking everything together.”

The legacy of legacy systems

Many of these legacy systems were hard to update. And no one really knew what would happen if they weren’t updated, Richard says.

“The fear was that when the internal computer clocks rolled over from 23.59 to 00.00 on 1/1/2000, these systems would encounter flat-out crashes or errors that would lead them to crash and disrupt things, ranging from power and water distribution to satellites and more,” he says.

Obviously, the world didn’t end.

While there were a few glitches, the world’s organisations and governments addressed the problem in time.

The next Y2K?

In 2019, cybersecurity experts are worried about bigger problems than two missing digits.

While there are many threats and vulnerabilities today to be concerned about, Richard says he’s particularly concerned about the nature of truth and what’s ‘real’.

“Threats to the integrity of data, information, and knowledge scare the living —- out of me,” Richard says.

“Things like unbounded AI (artificial intelligence) or ML (machine learning), enabled or generated deep fakes are a growing huge problem.”

This refers to the ability to make fake videos of real people.

Richard says another concern is how many people simply believe what’s presented to them is fact.

“To me [that] represents an existential threat to society and the world at large,” he says.

There’s also the 2038 problem, but that’s still 18 years away so no one’s really worried about that yet. Happy new year!