On the roof of a Curtin University building sits a row of black, white and silver car panels.

The panels – sourced from a sunroof fitting company – are almost never seen.

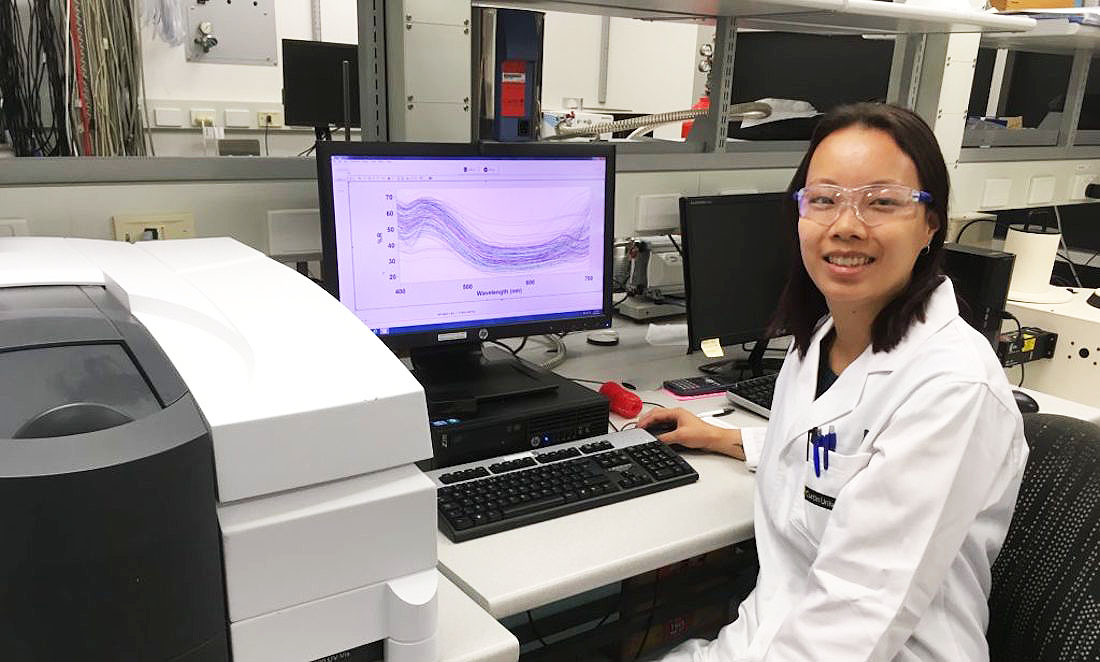

But every few months, forensic scientist Dr Georgina Sauzier collects a bit of paint from each panel and takes it to her lab.

It’s an experiment that’s been going for more than five years, and its findings could prove crucial in a criminal case.

Car paint clues

Georgina says most testing of car paints in forensic research has been done with new samples – but few people own brand new cars.

“The average car in Australia is about 10 years old,” Georgina says.

“So it’s going to have been exposed to sun and temperature and extreme environments.

“We want to replicate those conditions so that any information that we gain could be used for a real fragment of paint that’s come from a crime scene.”

Georgina uses infrared spectroscopy to study the clear outer coating that protects the rest of the paint.

This technique can determine the ‘chemical fingerprint’ of a substance based on how it absorbs infrared light.

Each molecule interacts with specific light frequencies.

Measuring these interactions can tell chemists what molecules are present and how they might be changing.

For example, Georgina has discovered that the resin in the outer coat of car paint can begin to degrade within two years.

“We found that the bonds holding the resin together are starting to break down,” she says.

“This changes the composition of the paint, which could affect how that paint evidence is interpreted by forensic scientists in a criminal investigation.”

Written in ink

Georgina is also researching how inks change over time by studying handwritten documents.

She uses visible spectroscopy to determine the exact colour of the ink.

Georgina might be able to age a document, or tell different inks apart, by studying colour differences too subtle to be seen with the naked eye.

It might also be possible to test whether someone has changed a document, such as by adding an extra figure to a bank cheque.

“We’ve actually found that it can take as little as one week for the ink to change and for us to detect that using spectroscopic measurements,” Georgina says.

The paint study was done in collaboration with forensic scientists at the ChemCentre, and the ink work with forensic document examiners at Document Examination Solutions.

Infrared forensics

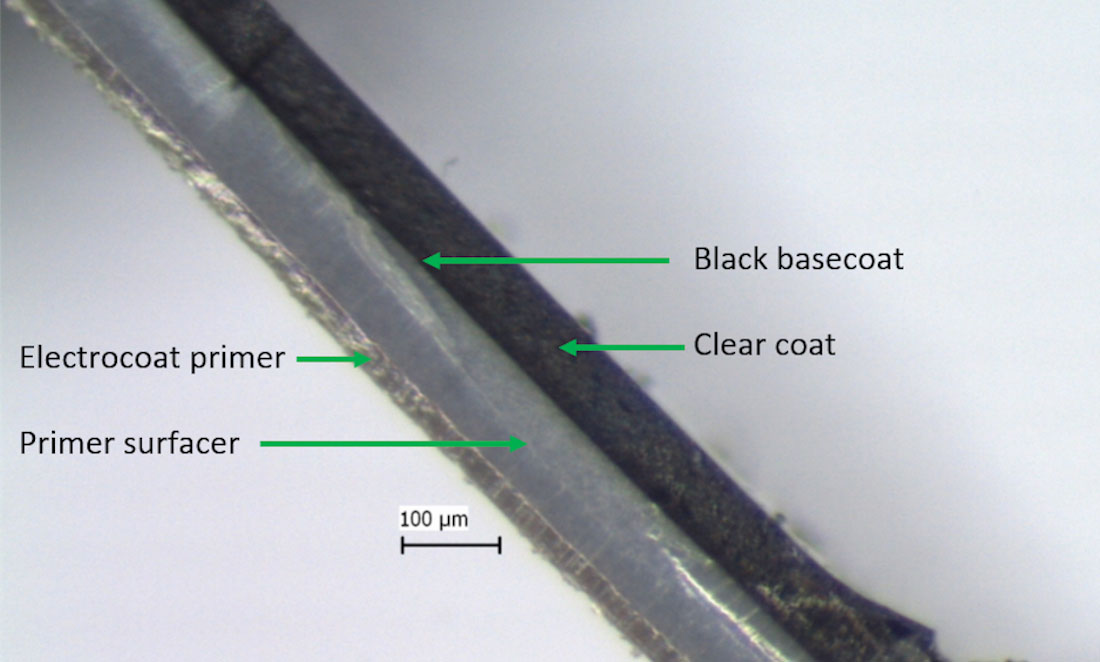

In October, Georgina visited the Australian Synchrotron in Melbourne, a facility that uses high-speed electrons to generate incredibly bright light.

This light can be used for spectroscopic measurements on a tiny scale, allowing her to map the chemical makeup of different layers of paint on the car panels.

Each layer can be thinner than a human hair.

“This is something that we can’t do using our normal instruments,” Georgina says.

“We just can’t get enough resolution to tell the different layers – which can be only 20 microns thick – apart from each other.”

Previous Curtin research has also used the synchrotron to study the chemical makeup of fingermarks.

These marks are usually made up of natural skin secretions from our fingertips, as well as contaminants like food or cosmetics.

So if you leave fingerprints, ink or car paint behind after a crime, science is already on your case.