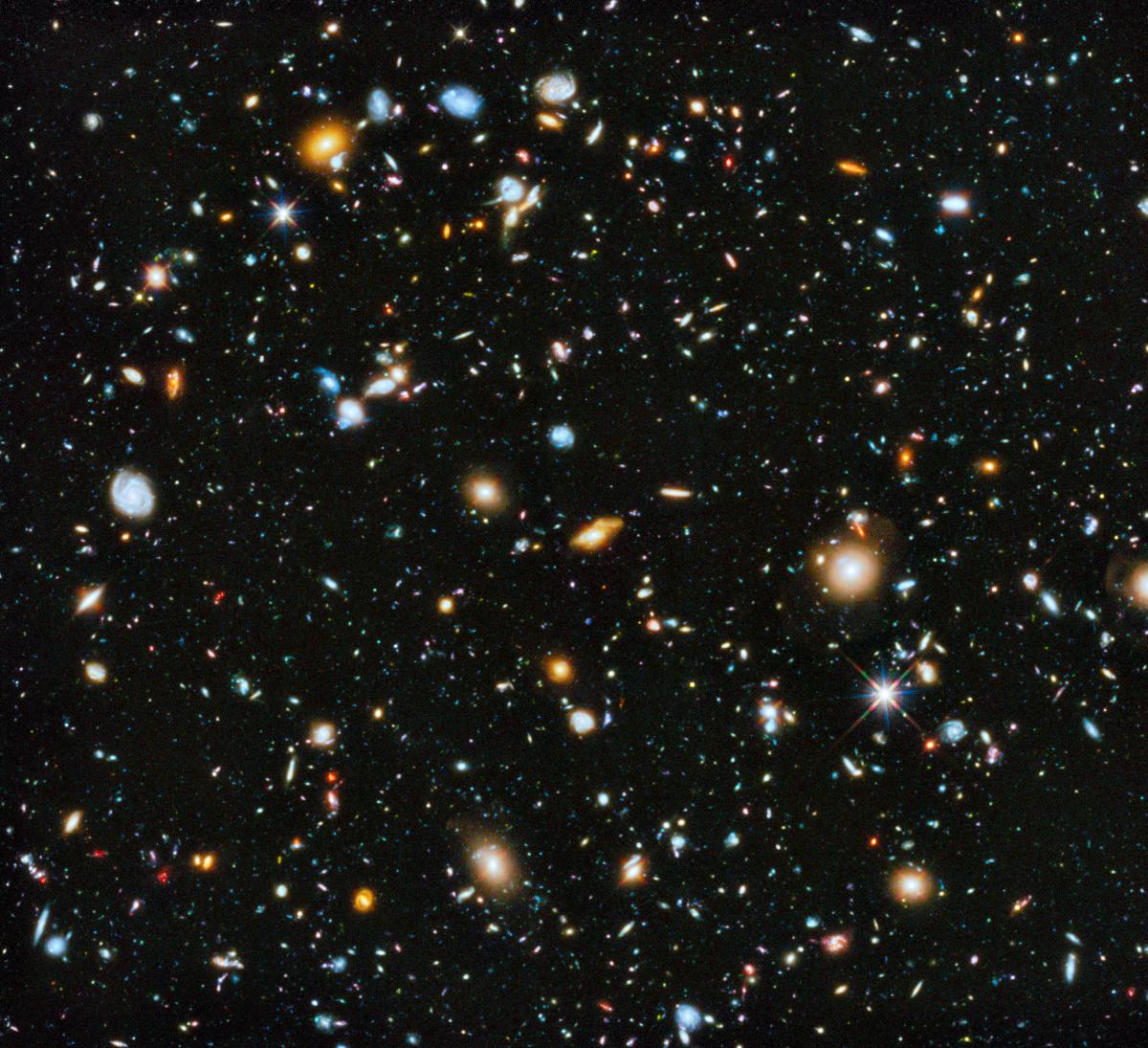

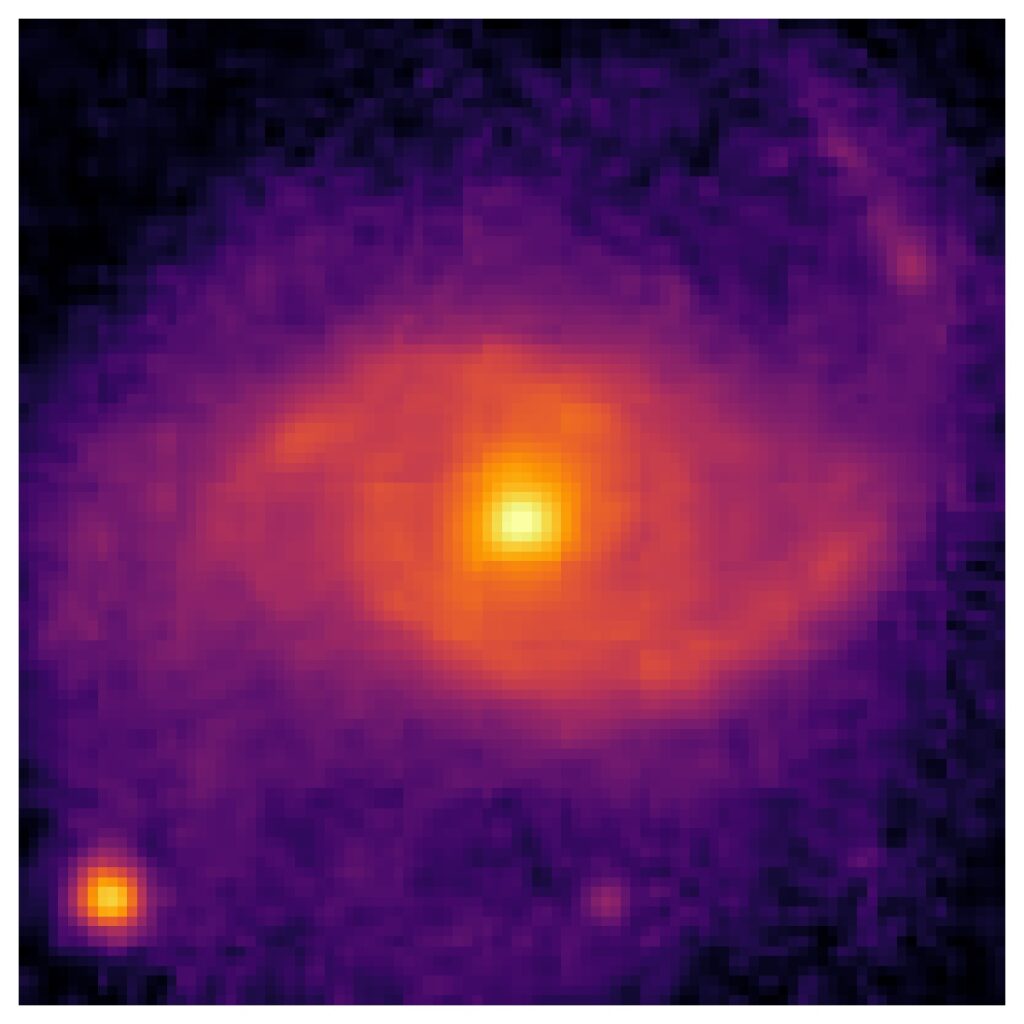

When you think of a galaxy, the first thing that comes to mind is a spiral. There’s a dense cluster of stars in the core and some big, sweeping spiral arms out to the side.

But that’s not the only kind of galaxy out there. Like people, galaxies come in all shapes and sizes. There’s disc shaped ones and spherical ones, neat barred spirals and messy irregulars.

Galaxies, sorted.

That shape isn’t just important for your sense of aesthetics when you’re picking a desktop wallpaper. It also tells us a whole lot about the universe, according to Mitchell Cavanagh, PhD candidate at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR).

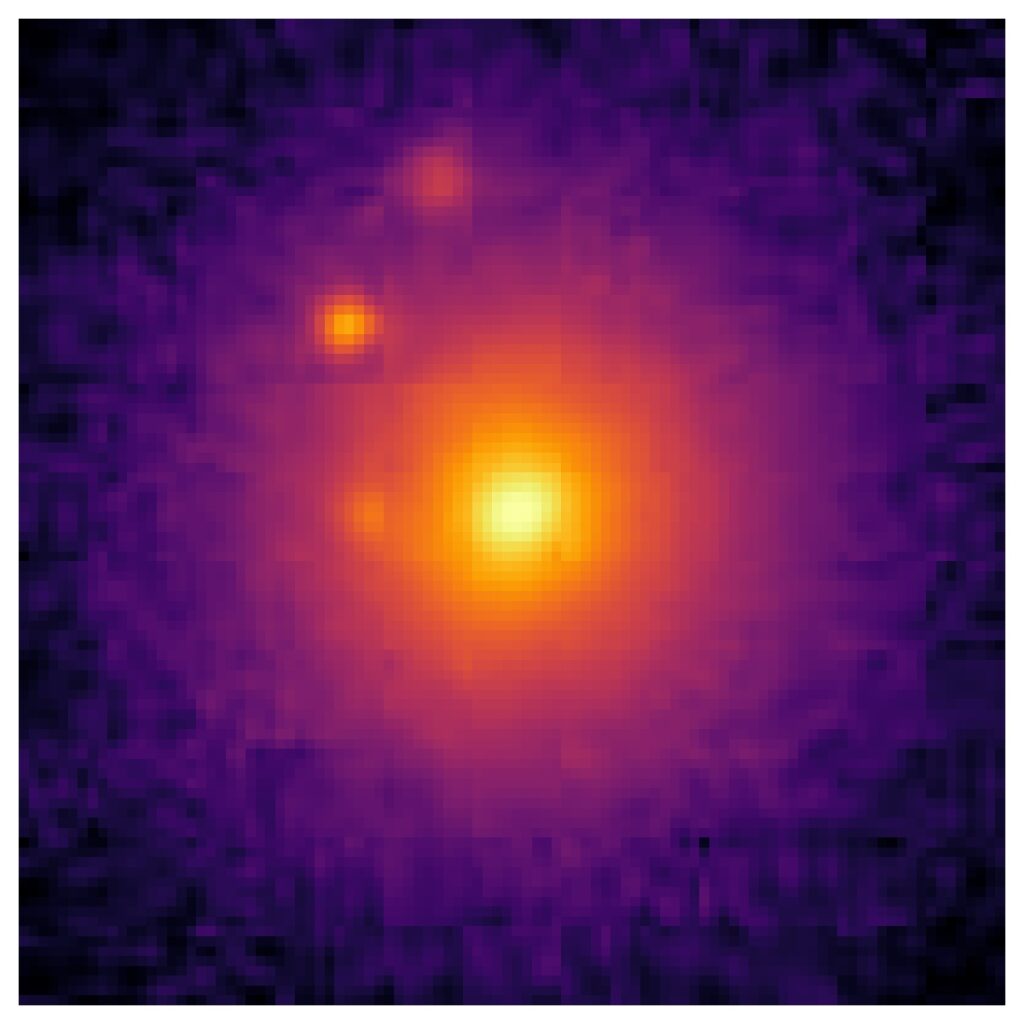

“We call ellipticals early types because they’re more prominent as you go out to higher redshifts in the earlier universe. Then your spirals, we tend to call late type because they’re more common when we look at the more-recent universe at lower redshift galaxies close to us,” Mitchell says.

“So just being able to track how that goes is quite important.”

The problem, as always, is that there are a lot of galaxies out there. The solution so far, through projects like the Galaxy Zoo (and ICRAR’s own AstroQuest), has been to enlist volunteer “citizen scientists” to help sort the data too. But with the amount of astronomical data coming through new projects like the SKA, even an army of citizen scientists may not be enough.

“You’re going to have billions of galaxies, billions of images. And just the sheer volume of samples that are going to be coming in – even with citizen science, you’re going to need a very big pool of volunteers,” says Mitchell.

Meet the AI-stronomers

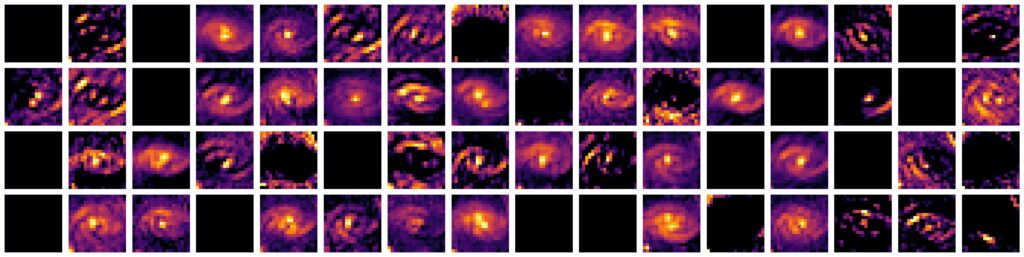

One solution could be a type of machine learning algorithm called a convolutional neural network or CNN. That’s exactly what Mitchell’s been developing. It runs on a regular desktop computer but can still sort through tens of thousands of galaxies in just a few seconds.

What sets Mitchell’s program apart from previous attempts is that it can sort more types of galaxy at a time.

“A lot of the neural networks in astronomy tend to just look at binary things, like is this an early type or is it a late type, things like that,” Mitchell says.

“Whereas we want to try and get into more detail. We want to look at more classes instead of just two.”

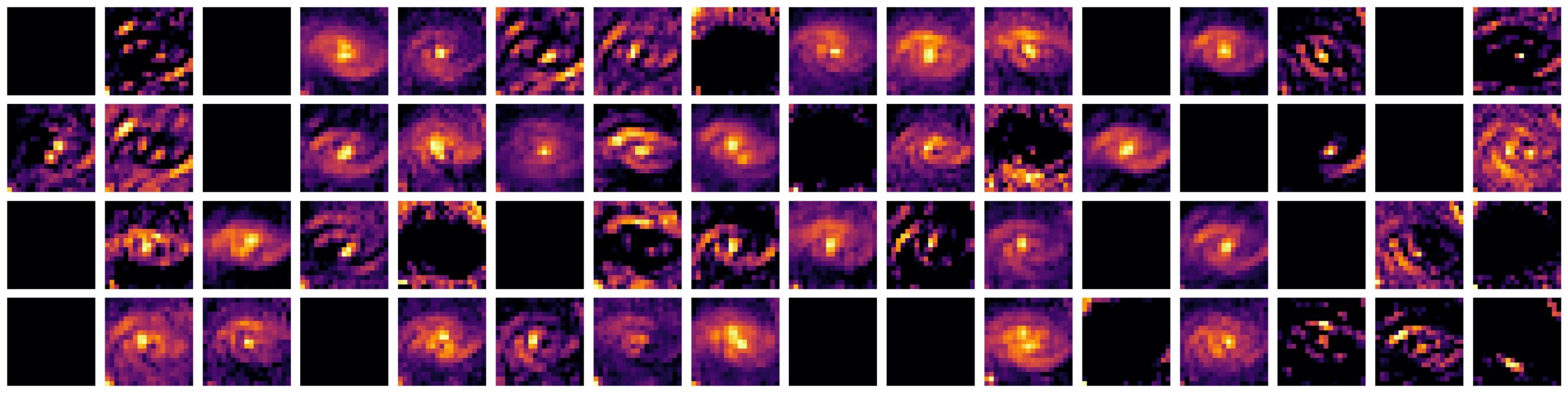

Neural nets, Mitchell says, have the potential to be faster and more efficient. They can also be used in situations that would be difficult, time consuming or just plain boring for human volunteers to do. That includes things like classifying simulated galaxies that don’t actually exist.

“Once you’ve trained a CNN, you can apply them to all sorts of other things – simulations and things like that – to do some cool science that compares those simulations to observations,” he says.

But don’t hang up your galaxy-sorting hat just yet. As always, there’s a catch.

Are the robots coming for my (volunteer) job?

When astronomers teach a human to sort galaxies, they’d describe the shape, talk about the important features, maybe draw a diagram and show a couple of examples to finish.

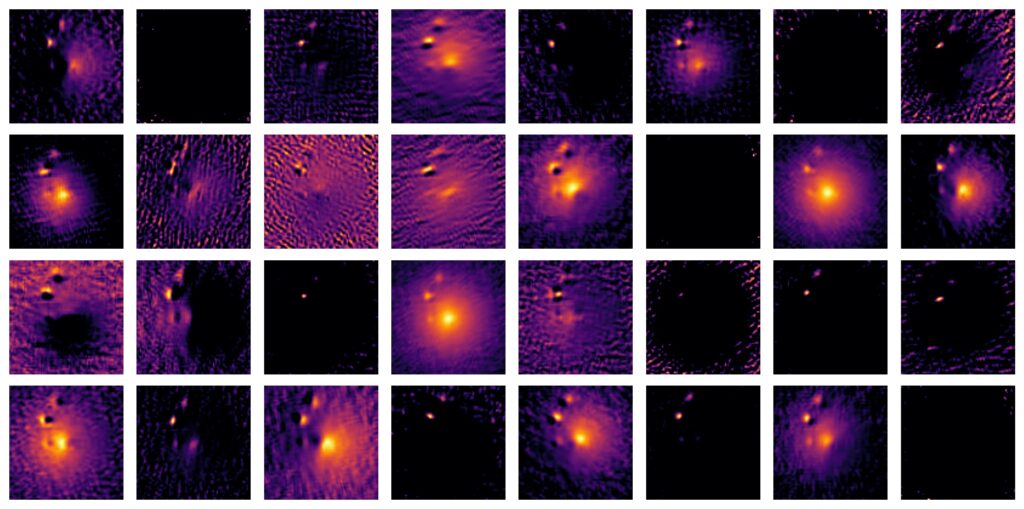

If we’re teaching an AI, they can only use examples – and where volunteers could figure out what a barred spiral is from one or two examples, a neural network needs hundreds.

“Fundamentally, a neural network is really only going to be as good as the data that you train it with,” says Mitchell.

And if we use some tricky techniques to look at how it’s “thinking”, the features of the images that it’s looking for don’t look at all like the ones we’d use as humans.

Training brains

This leaves us with a bit of a conundrum. We need our AI to sort our galaxies into types, but to train our AI, we already need to know what types our galaxies are.

Far from making human citizen scientists obsolete, AI-powered astronomy actually gives them a promotion – from doing the work themselves to being more like a coach or teacher.

“In a sense, the neural networks are built on top of the existing effort of citizen science.”

AI is really good at giving people exactly what it thinks they want. To use it for astronomy, we need an army of well-trained volunteers who want nicely sorted galaxies – and yes, that’s where you come in.