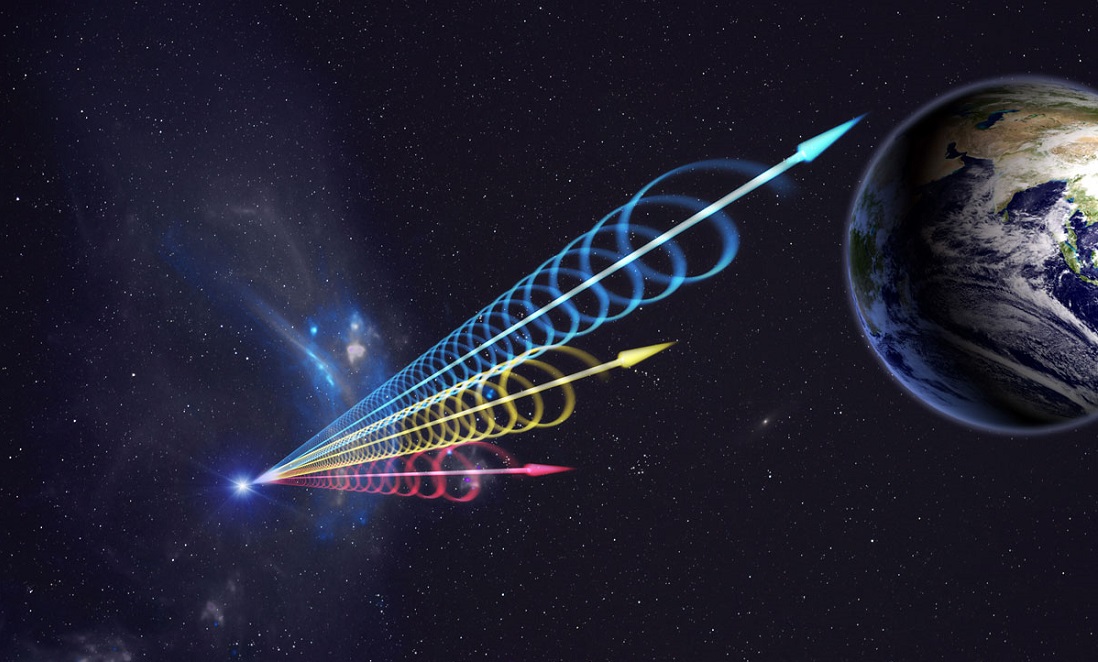

Fast radio bursts (FRBs) are flashes of light radiation from beyond our galaxy. They only last for a few milliseconds, but some bursts have as much power as the radiation of 500 million Suns.

The problem is, after one brief flash in the sky, they disappear forever. Until now.

Three years ago, a graduate student of McGill University named Paul Scholz noticed a fast radio burst first spotted in 2012—called FRB 121102—was repeating. This began a race to figure out the mystery behind FRB 121102 that last year began to show answers. This weird radio burst pulsing out from a dwarf galaxy about 3 billion light years away calls into doubt some theories researchers had on fast radio bursts.

The biggest problem with looking for fast radio bursts is you don’t know when and where one will flash next. You have to watch the skies and hope you get lucky. FRB 121102 changes all that.

Hoping to get lucky

Now, observatories around the world are pointing at the repeating burst to uncover the hidden story of these strange flashes.

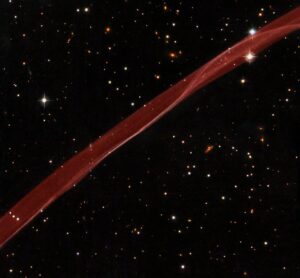

Researchers across the world are now guessing at the origins of fast radio bursts. Most guesses involve a neutron star plunked into the middle of some extreme conditions: black holes, supernovae remnants, colliding with another neutron star or even collapsing in on itself.

What can they teach us?

One reason scientists are so interested in learning more about fast radio bursts is they can act like a cosmic radar. Dr Charlotte Sobey of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) says we would only be able to receive the signal, but it would give us information about the space it passes through on its way to Earth.

The way this works isn’t much different from a submarine’s sonar. The radio signal is sent out from FRB 121102, and as it hits things in space, the signal changes, carrying the information with it. Once the signal gets picked out by our receivers, we can use that information to figure out what it encountered on its journey.

FRB 121102 is already taking scientists the first steps towards this cosmic radar. How? Well, this burst doesn’t just repeat, it’s also completely polarised.

Signal polarisation means the radio wave is being warped. Astronomers think this can only happen if the signal is travelling through a powerful magnetic field on the way to our planet.

At the moment, astronomers at Aricebo Observatory, Puerto Rico, who are measuring FRB 121102 think it is coming from a strong young neutron star hanging on the edge of a black hole. Another possibility is if the signal is travelling through a plasma cloud on its way to Earth.

The polarisation is the same each time FRB 121102 repeats. This leads scientists to think whatever the signal is travelling through is staying put. So somewhere between FRB 121102 and Earth is a huge cosmic event hanging out in the sky.

Even if we figure out what created FRB 121102, it still might not mean all fast radio bursts happen the same way. But for each one we find and measure, we get another cosmic radar scan of some of the most destructive and powerful forces in the known universe.