In a dusty paddock near Mingenew (around 400km north of Perth) lies a smattering of dongas and satellite dishes that make up the Western Australian Space Centre (WASC). The green beam of light shooting into the sky comes from the Yarragadee Geodetic Observatory, part of the WASC. It shares a boundary with a chunk of my family’s wheat and sheep farm.

“Lasers shooting satellites sounds very futuristic, but the Yarragadee Geodetic Observatory has been here since 1979,” says Sandy Jones, Assistant Manager at the Observatory.

“It’s a NASA controlled site. They own most of the equipment. They maintain it and they’re quite involved in the day-to-day running, although most operations and repairs are carried out by Geoscience Australia.”

It’s always sunny in Yarragadee

NASA chose the Yarragadee site for an ordinary reason: Mingenew, on average, has the most number of sunny days in a year.

“We need clear weather, it’s that simple. Because when we’re affected by clouds, we can’t shoot the laser through them,” says Sandy.

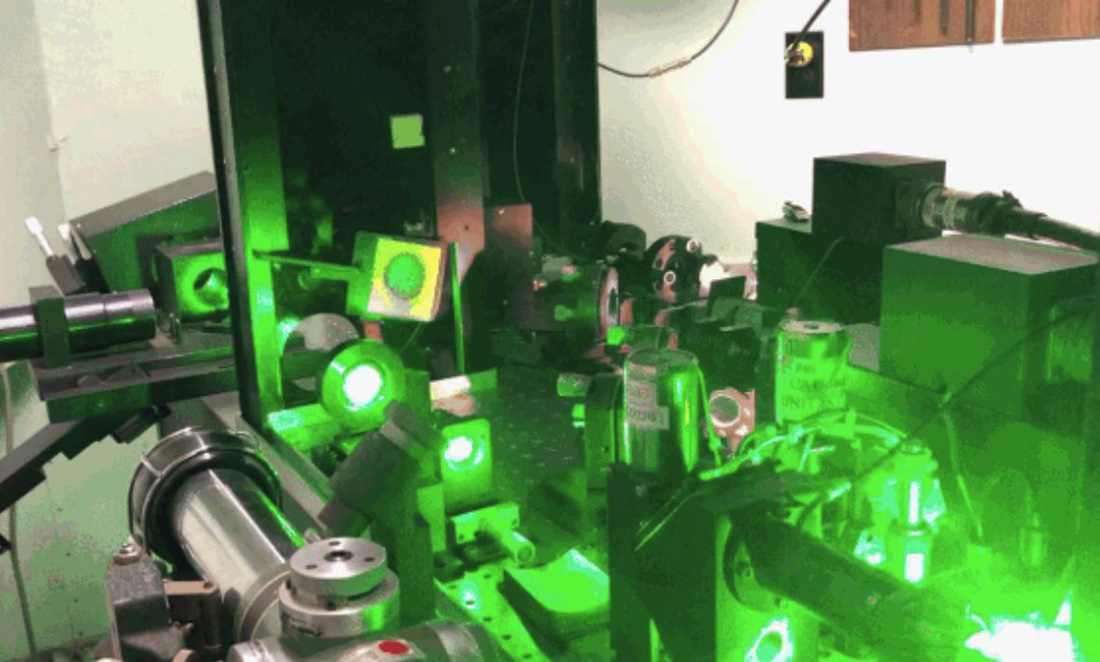

Laser beams and space machines

Yarragadee’s laser is one of four geodetic experiments run by Geoscience Australia. It was designed to measure exactly where Australia is in relation to the rest of the world, the centre of the Earth and the cosmos.

Sandy explains that the Satellite Laser Ranging experiment uses the laser to see how far a satellite moves from its predicted orbit.

“Essentially, we shoot a laser at a satellite. When it bounces off the satellite, we record how long it takes to travel between us on Earth and the satellite.”

Since the speed of light is constant, the team are able to measure the time of flight of the laser beam, and then determine where the satellite is relative to the centre of the Earth.

The data collected then goes on to make up the building blocks of anything related to positioning – cartography, geodesy, Google Maps and GPS.

So shiny

Geodetic satellites are the most useful targets for Satellite Laser Ranging since they are exactly like disco balls. These satellites have a stable orbit and are covered in retroreflectors, which enables the laser to easily reflect the laser beam.

Aside from a few kinds of satellite that are off limits to the laser because of the specialised technology on board, the observatory team aren’t particularly fussy with how they choose their targets.

“Literally any satellite that has a retroreflector, we will try to hit it with the laser.”

Pew Pew

Yarragadee’s MOBLAS-5 laser is eye-wateringly fast. Keeping in mind that one picosecond is one trillionth of a second, or 1.0×10−12 seconds, the laser pulses are very short, less than 200 picoseconds per pulse. The laser can fire two times per second for far away geostationary satellites, and up to 10 times per second for low Earth orbit satellites.

After controlling for a bunch of variables, Sandy calculated the total elapsed firing time of the laser in its lifetime is “in the ballpark of 1 and a half hundredths of a second” for the entire 40 years the laser has been in operation.

But what would happen if you put your hand in front of it?

“While it’s obviously a bad idea, it wouldn’t burn a hole through your hand.”

Sandy laughs that the laser would do more damage to your eyes. This explains why, upon a visit to the laser room in the back of a caravan-like structure, you are issued with yellow-tinged cat eye glasses to protect your eyes. Groovy.

The Australian tectonic plate is moving at a fairly cracking pace – approximately 7cm in a northeast direction each year. This means updates to services such as GPS and Google Maps via data collected from geodetic observatories like Yarragadee are critical for maintaining accuracy.

Sandy highlights the importance of representing the mapped world as closely as possible to the actual world. The pace of the Australian plate movement means it would only take 14 years to move 1 metre away from today’s GPS and Google Maps reference points.

“There is a whole world of reference frames – datums – that when put together form the Australian Geospatial Reference System, which can be used to convert geospatial information forwards or backwards in time.”

From there, Geoscience Australia works on putting these all online and coded up for industry users.

In a world more reliant than ever on navigation services and facing an imminent future with technology like autonomous vehicles, Yarragadee’s data will no doubt continue to play a large role in pinpoint precision measurements.

“Columbia, this is Houston through Yarragadee. We’re standing by.”

When NASA launched their Space Shuttle program in the early 1980s, Yarragadee was alongside a vast network of communication stations dotted across the world. These stations provided vital communication support between Houston Mission Control and the astronauts on board the Columbia and Challenger spacecrafts.

NASA’s archives show Yarragadee was involved in at least seven manned missions. These ran from the very first Shuttle mission Columbia in 1981 to Challenger in 1984.

These significant moments in the station’s history remain neatly captured on cassette tape.

Unfortunately, improvements to NASA’s Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System made the Yarragadee communications link obsolete by the end of the 1980s.

Beyond the backyard

Even though there are plenty of Satellite Laser Ranging stations around the world, many of which use cutting edge of advanced laser technology. But Yarragadee remains key to gathering geospatial information for the world’s scientists.

“We are the most productive station in the world. We collect more data than any other station using this fairly old school equipment,” says Sandy. “We’re very lucky and proud of that fact.”