Isolation feels like a pandemic purgatory. Life has felt like it has ground to a halt. Nothing changes.

But isolation doesn’t mean that everything stops. In fact, isolation can create a perfect set of circumstances for change and experimentation. And we don’t mean your at-home hairdressing adventures. We mean science.

Evolutionary, my dear Darwin

Isolation is a key player in evolution. It’s both a trigger and an outcome.

It’s that first story many of us hear about in biology.

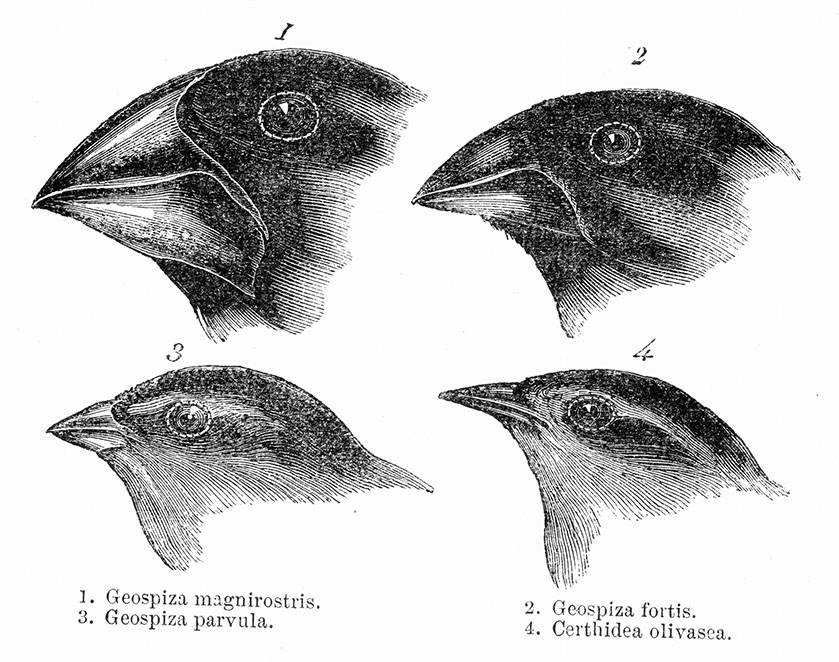

Charles Darwin saw finches living on separate islands and realised that they looked a bit different from each other. This led to his famous theory: different environments present different challenges for animals.

Animals with more favourable traits are more likely to survive and breed. Their babies carry on those favourable traits and, over time, new species evolve.

A crucial part of this evolution equation is isolation. Being physically separated by the ocean meant the gene pools of each bird group couldn’t intermingle. So the genes for each favourable trait could be passed on within each population undiluted.

Behaviour can also be isolating, like if two groups of animals live in the same area but act differently. Say if one group of birds had a mating call that was a turn-off to the other.

Or, for example, if they’re active at different times of the day. Imagine trying to date someone who works night shifts when you’ve got a steady 9 to 5.

Creations of isolation

Sometimes isolation changes animals so much they evolve into a new species altogether. But how do we tell if an animal is one species or another?

We might use common sense to tell cats from dogs. For scientists, though, species are defined by isolation. In this case, it’s reproductive isolation or the inability for their genes to mix and produce offspring that can have babies of their own.

For example, a zebra and a donkey can produce a hybrid – the zedonk. But the zedonk is sterile, born into a childless life, a barren product of its parents reproductive isolation.

But this is just for animals, right?

Isolation is unlikely to turn humans into a new species any time soon, but that doesn’t mean that we’re immune to its effects.

Researcher Harry Harlow, best known for his harrowing studies of maternal affection, also experimented with isolation chambers. These are not to be confused with sensory deprivation chambers invented by dolphin-loving, LSD-tripping researcher John C. Lilly in the 50’s to explore the origins of consciousness. In fact, there are hints that these isolation chambers might actually help treat mental health problems.

Harlow’s isolation chamber, on the other hand, was nicknamed the Pit of Despair. It was designed to produce an animal model of depression. The experiments he ran were truly gruesome, even in light of the relaxed approach to ethics employed by scientists of yesteryear. American literary critic Wayne C. Booth perhaps summed it up best:

Harlow proved “what we all knew in advance – that social creatures can be destroyed by destroying their social ties”.

Though Harlow’s work remains widely condemned, it highlights the importance of companionship to human cognitive and social development.

Is there (happy) life on Mars?

You might think that isolation experiments on humans could only exist in the psychology labs of the 70s. But on the rocky slopes of the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawai’i, researchers continue to push the boundaries of what we know about humans living in isolation

Or they were until 2018, when one of the volunteers was admitted to a medical centre and Mission VI was suspended.

(Don’t worry. It wasn’t the isolation that drove them there, just an electric shock.)

Hawai’i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) is an initiative of NASA’s Human Research Program. The aim is to understand how to keep a space flight crew safe, happy and healthy on a mission to Mars.

After all, how disheartening would it be if, after all that work to put humans on the Red Planet, the astronauts couldn’t keep it together?

Inside a dome that looks like half a golf ball, crews of between four and eight spent up to a year simulating life on Mars.

Their daily routine mimics how astronauts live, including simulated spacewalks on the barren volcanic landscape surrounding them.

You can listen to the fourth chapter of this isolation experiment on The Habitat podcast.

The crews’ audio diaries share their experiences with listeners from the moment they set foot into the dome to when they ‘return to Earth’ 366 days later.

It’s a compelling look at how relationships develop and change when we’re isolated together.

And it makes for fascinating listening while you wait for our own COVID-19 isolation experiment to play out here in WA.