Getting sick in space is no joke. You’re stuck, surrounded by the most advanced equipment in the world, most of which is useless if you need a medicine you didn’t think to bring.

Even taking a pill has its problems as the constant radiation breaks them down.

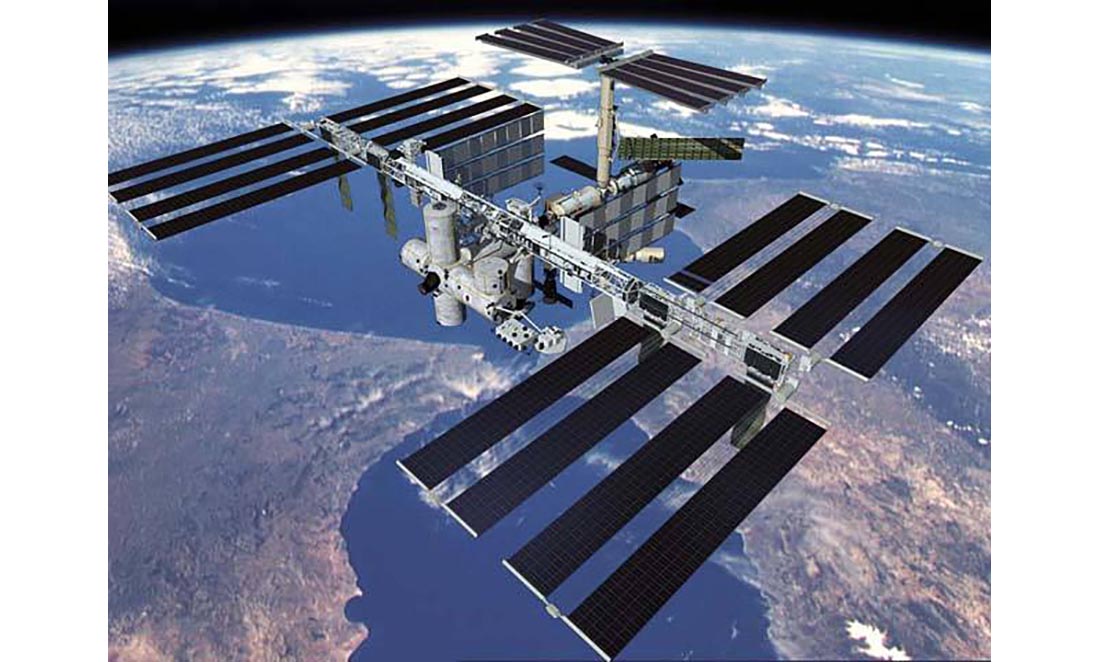

Professor Volker Hessel is a researcher at the University of Adelaide who has sent medicine up to the International Space Station (ISS) to test how pills survive in space.

The plan is to understand how we can make space drugs that can last the 3-year trip to Mars.

In space, no one can hear you sneeze

Astronauts are extremely fit for a reason. Space is incredibly stressful to human bodies. Microgravity means astronauts lose 1–2% of their bone mass each month.

Radiation also changes astronaut DNA.

Medicine has an important role on the ISS. It saved an astronaut from a serious blood clot in 2016.

On the Apollo 7 mission, Wally Schirra’s head cold meant every decongestant and tissue on board was used.

It was such a disaster it led to a crew mutiny, which banned the team from ever entering space again.

Take your protein pill and put your helmet on

Volker’s team sent up two medicines: ibuprofen and vitamin C.

“No medicine survives in space longer than 1 year. Many don’t last that long,” Volker says.

This is a big problem for future Mars trips. Astronauts would run out of medicine a third of the way there.

Once Volker understands how these medicines are affected by radiation, he wants to find ways to make them last longer or even make them in space.

Ibuprofen is one of the most commonly used drugs in the world. It’s a market that makes US$294.4 million per year with millions of tablets being manufactured.

It’s a great starting point. It’s versatile, easy to make and is already the subject of decades of research.

“There’s a lot of research on radiation’s effects on ibuprofen because we try to decompose it to reduce its environmental impact here on Earth. We know its lasting effects in water contamination, which is important when you’re reusing water in space,” Volker Hessel says.

Orbital decay

The main goal of Volker’s research is to see what effects space has on ibuprofen tablets. There are two parts to the mission, with tablets sent up to the ISS last year and early this year.

One set of tablets is inside the ISS while one is outside the station, exposed to solar radiation.

Both samples will return to Earth for Volker to test their radiation decay.

“Because of the cost of space, we could only bring 60 tablets. So we’re continuing experiments on Earth, trying to replicate space conditions.”

Space refineries

On Earth, ibuprofen is made by decomposing and refining petroleum to produce two different chemical molecules: benzene and propylene.

When they’re heated in acidic conditions, they combine to make ibuprofen.

The catch is that petroleum on Earth mostly comes from fossilised life, trapped beneath the Earth millions of years ago.

But there’s little to no space petroleum. This means we need to rethink how we make medicine.

“Around half the tablet’s contents are organic cellulose: plant fibre. We removed that, which reduces the tablet effectiveness but means they could be made in space,” Volker says.

So future research will look at how we can make these everyday medicines when we don’t have access to Earth’s vast resources.