Our ability to do astronomy hinges on one seemingly obvious question: what colour is the night sky?

Travel from the city to the country, and you’ll see the sky’s palette shift from the harsh orange to the country’s whorls of blue and purple.

Invisible to us, there is another shift from city to country. Radio waves give us the internet, the ability to communicate and the rest of the modern world.

As buildings are replaced by trees, radio towers become further apart and radio waves grow weak.

But as the night sky is getting busier, even these dark places are under threat from above.

Our universe keeps on expanding and expanding

Astronomers observe the universe using telescopes that catch light and radio waves.

Most places in the universe are too distant for us to travel to. Instead, light and radio waves let us observe the 70 billion trillion stars (a 7 with 22 zeroes after it) in the observable universe.

Light and radio pollution from the modern world can drown out these signals.

Astronomer and science communicator Fred Watson knows the problems a busy night sky can bring.

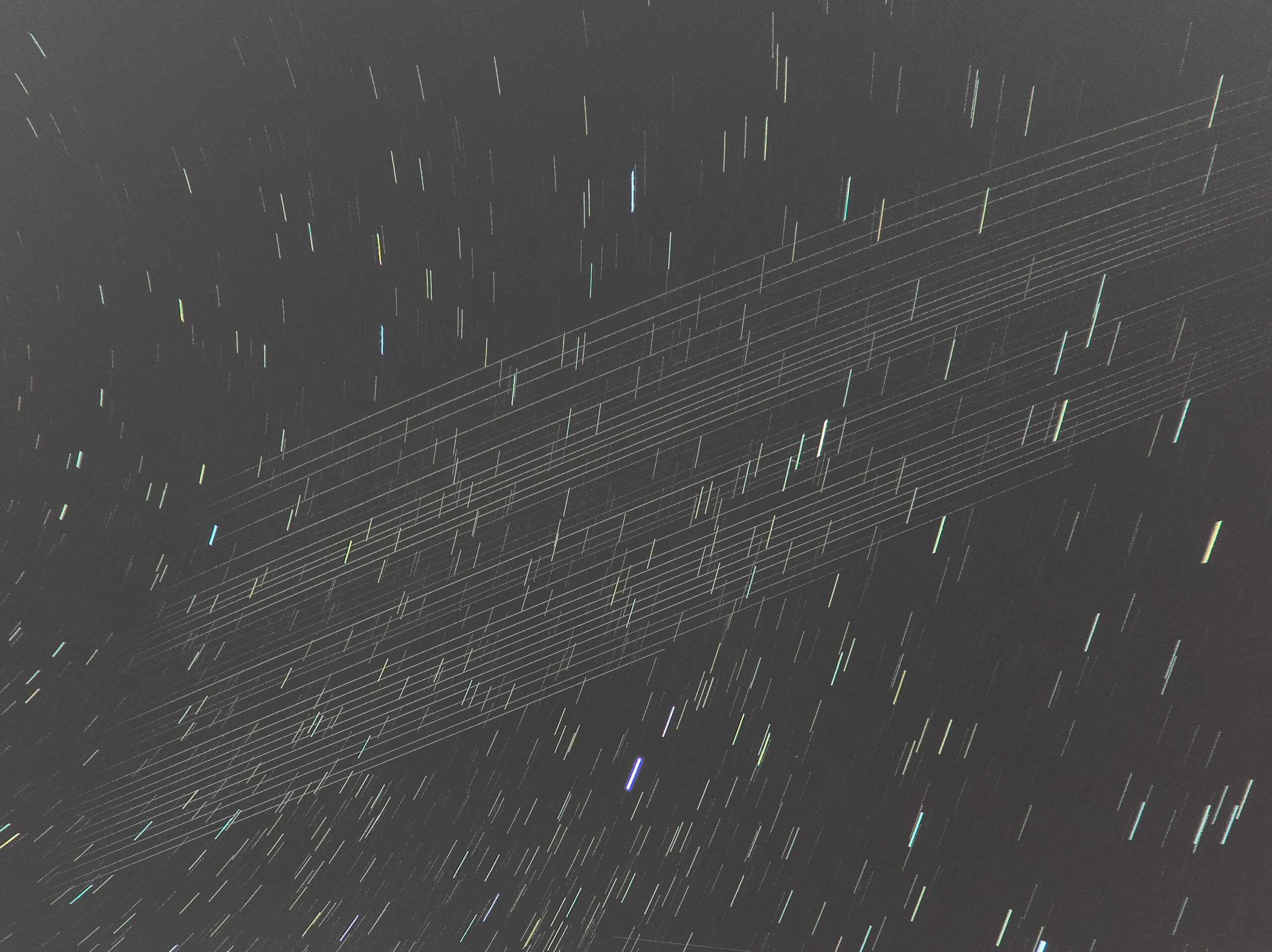

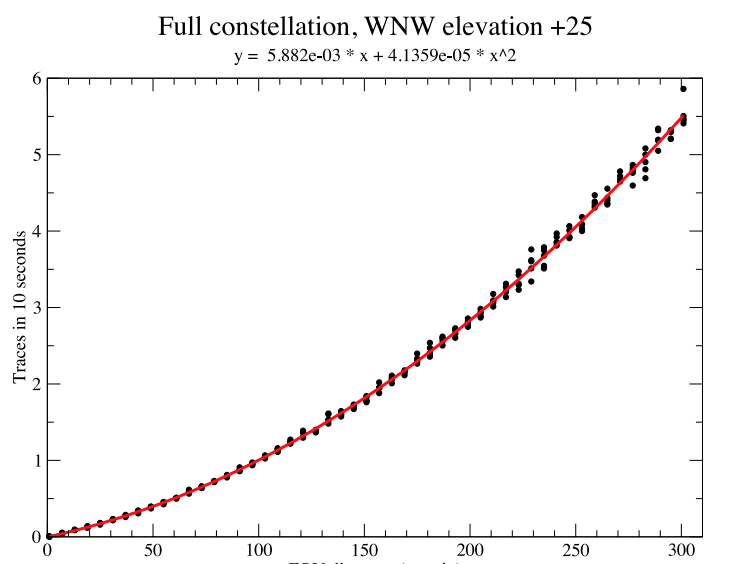

“In the next decade, we’ll see 90,000 more satellites in the sky. That does not mean the end for ground-based astronomy, but it certainly presents problems,” says Fred.

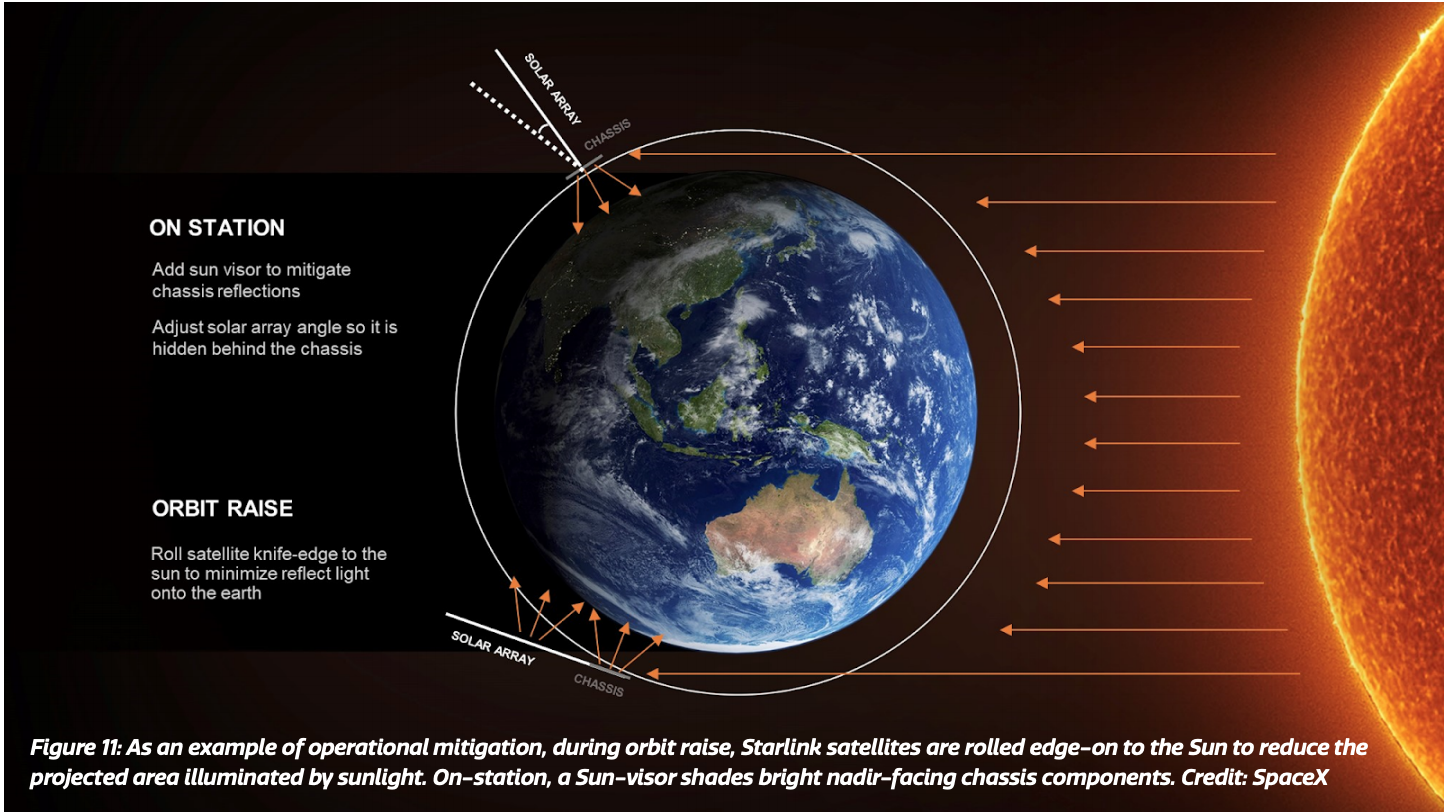

New satellites can pollute our night skies. They reflect light from the Sun at night, and their messages to Earth are in radio signals.

A Starlink satellite is 10 trillion times brighter than most other things in our skies. SpaceX plans to launch over 40,000.

Other companies, like Amazon and OneWeb, have similar plans.

The impact of these satellites on observatories will be huge.

As fast as it can go, at the speed of light you know

Widefield telescopes, telescopes that view large sections of the sky, are especially vulnerable to this pollution.

The Vera C Rubin observatory in Chile is predicted to have 50% of its images affected by satellites.

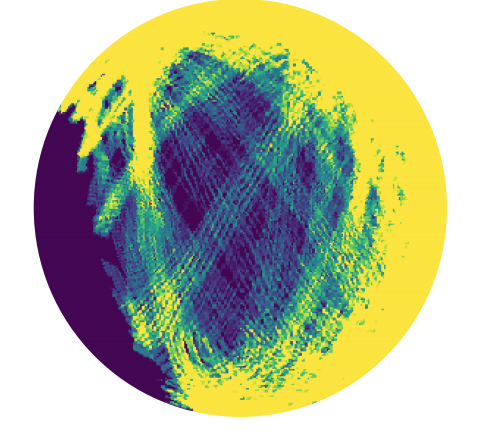

WA’s Murchison Widefield Array is even larger and will have to deal with more pollution in radio waves.

“Observatories [operating in the radio range of 50–350MHz] will need to increase their observation times by 70% to counteract the effect of the Starlink satellites,” says Fred.

So what can we do?

Windows of Opportunity

Nobody wants to lose Earth-bound observatories.

They have helped us discover 4000 planets beyond our Solar System and watch black holes merge.

But we also need communications satellites.

The United States’ NOIRLab is part of the National Science Foundation. They say observatories can build new software to erase satellites from observatory data.

Companies can help by pointing satellites 20 degrees away from observatories as they pass over.

“There has to be compromise on both sides. Companies and astronomers can agree on observation windows,” says Fred.

But what will happen if we keep sending thousands of satellites into orbit?

Looking at the dark side of the Moon

One solution, as our skies get more crowded, is to build observatories on the dark side of the Moon, but this poses its own problems.

“The problem with the Moon is it gets 14 days of daylight, then darkness. You could build observatories, but they would be more difficult than on Earth. They would also be more expensive, but spaceflight is getting cheaper.”

NASA is planning to build a Moon base by 2050. Other space agencies are looking at moving to the Moon as well. These missions could help lay the foundations for Moon observatories by 2100.

The future might be filled with shining satellites instead of stars. But for now, businesses and astronomers need to work together so we can keep discovering our universe.