Time to take a deep breath.

In …

Out.

Wasn’t that relaxing?

But for some living things on Earth, the air we breathe is incredibly dangerous.

So dangerous, in fact, that it caused the first mass extinction event on Earth. The Great Oxygenation Event almost completely wiped life from Earth about 2.4 billion years ago.

Today, some anaerobic (oxygen-free) lifeforms still eke out an existence. They cling to airless pockets around the world, consuming toxic metals in place of oxygen.

But where can we find these toxic, hidden pockets of life?

Aqua in the Atacama

The Atacama Desert in Chile is Earth’s driest and oldest desert.

Until 2015, the desert had gone without rain for 500 years.

It’s so inhospitable, researchers use it to study what life might be like on Mars. It’s also where an American research team went looking for the secrets to Earth’s early lifeforms.

Dr Brendan Burns is a microbiologist at University of New South Wales who helped study these mysterious life forms.

“[Team leader] Pieter Visscher got me on board to analyse the molecular data that would help piece together the story,” says Brendan.

A toxic salt flat

The Salar de Atacama – the Atacama Salt Flat – is a vast white plain that burnishes gold to the desert, then rises up to the Andes mountain range.

On this salt flat is a shallow lake, sheltered by dunes, called Laguna La Brava.

The water here is incredibly salty and alkaline – like a diluted form of drain cleaner. The volcanic rock beneath the lake has seeped corrosive sulfides and deadly arsenic into the water.

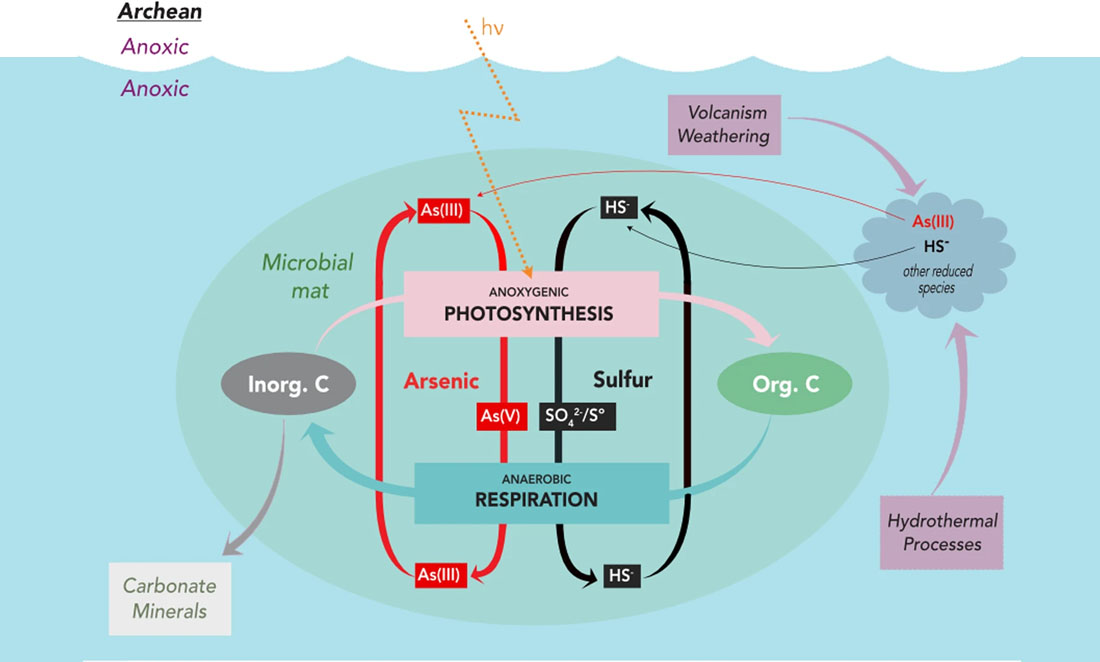

In the lake’s airless soil, purple bacteria use sunlight to photosynthesise these toxins for energy, the way other plants use carbon dioxide.

“You need an electron donor in the photosynthesis. Chemicals like sulfur, iron or, in this case, arsenic can donate their electrons,” says Brendan.

The harsh conditions needed to sustain this bacteria are rare, but Australian rocks hint that this kind of toxin-breathing life may have once ruled the Earth.

Water at the Bar

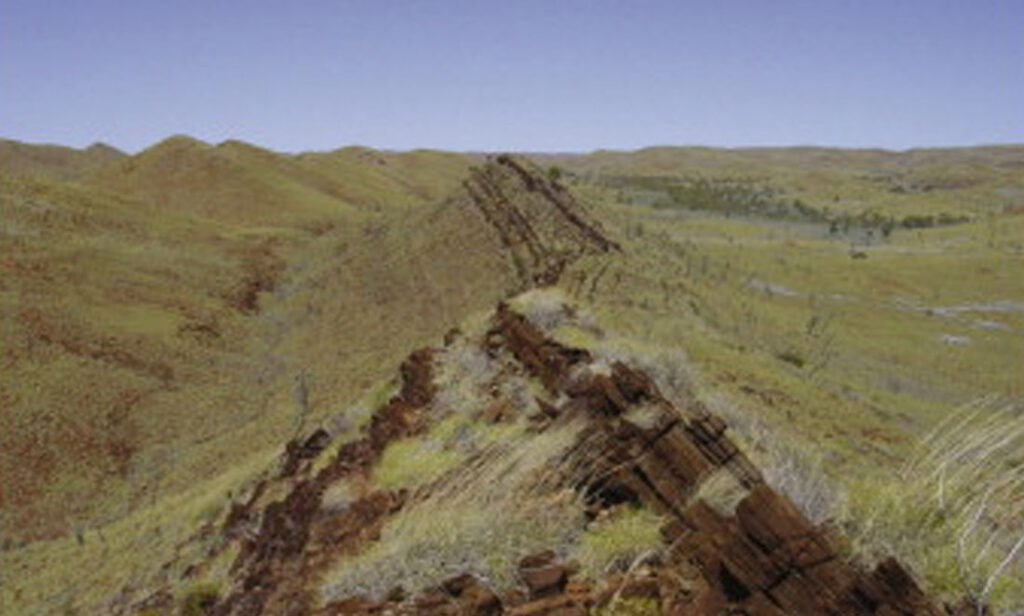

Ancient coral reefs called stromatolites dot the dry bush of Meentheena Station in the Marble Bar.

These strange rocks are fossils of 2.7 billion years ago, when a lake submerged the station.

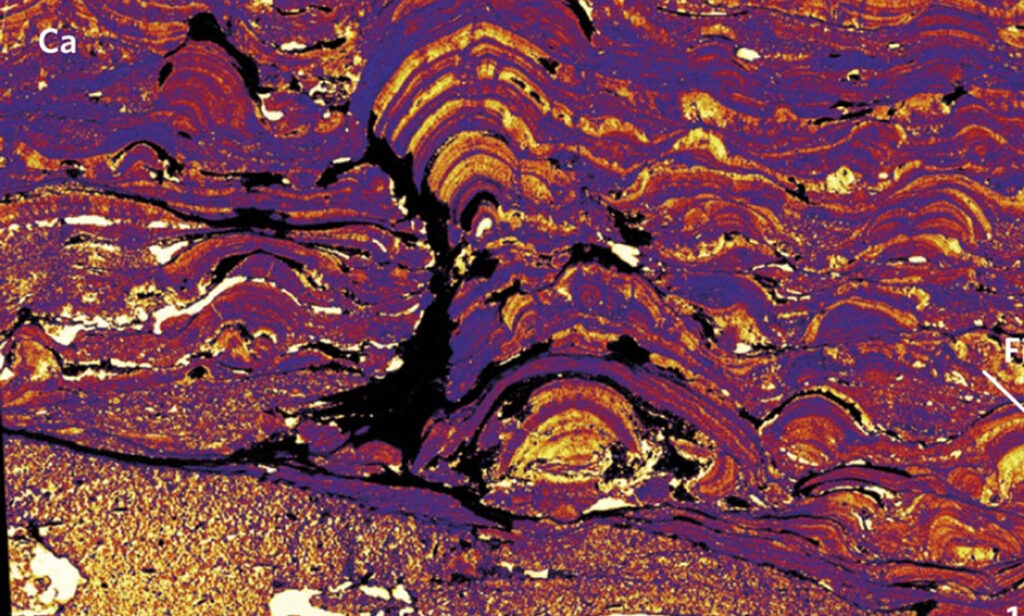

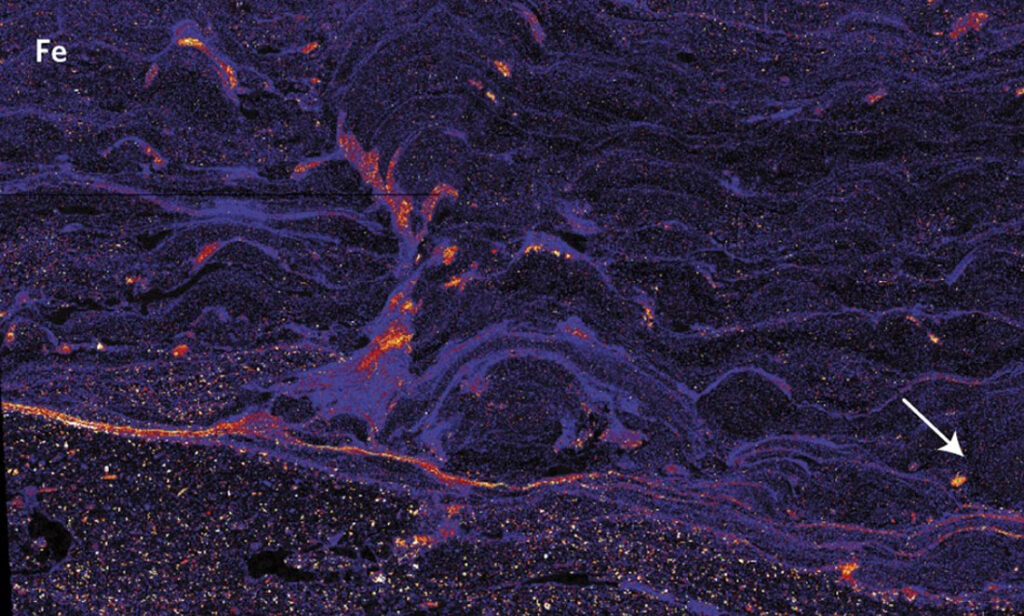

Cemented into the rocks are fossils of algae that lived during this period. Their DNA has eroded in the billions of years since their death. All that remains are the chemicals their bodies left in the rocks.

X-ray vision

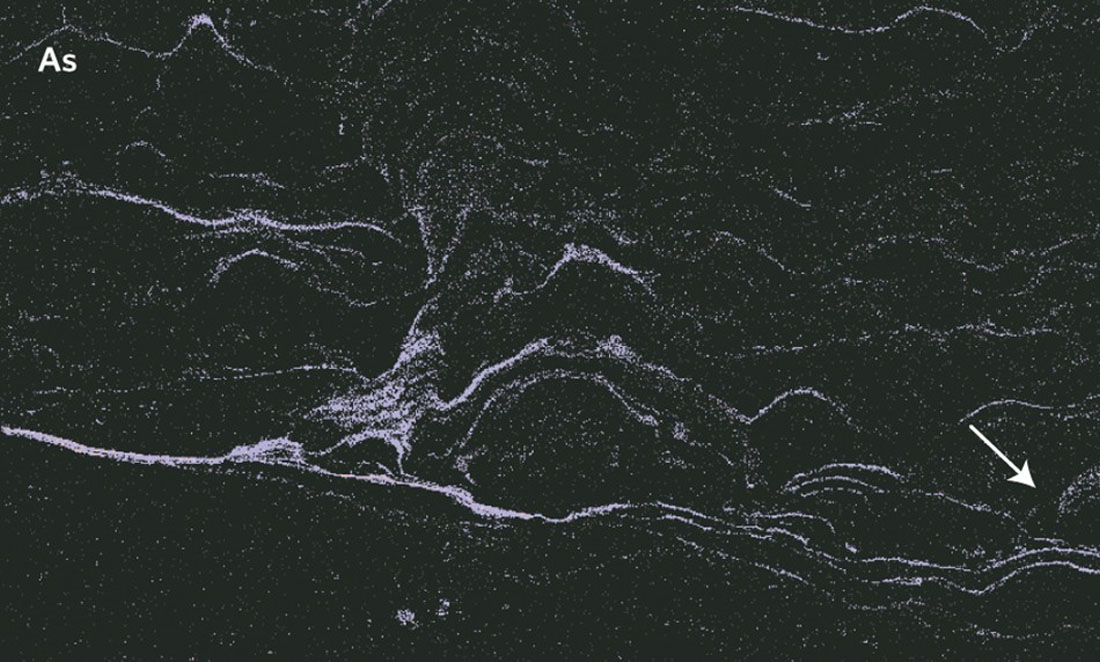

A French research team from Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris studied these chemicals using a synchrotron. This is a football-oval-sized X-ray machine that energises electrons until they emit flashes of light.

These flashes showed arsenic in the rock.

This was proof that the ancient algae consumed arsenic, like the bacteria from Salar de Atacama.

It was a link spanning one end of Earth’s history with the other.

“What’s really cool about these modern systems is we’ve got living organisms. We can isolate DNA to look at the photosynthetic pathways. You can’t do that with the fossils – the DNA has degraded,” says Brendan.

Shark Bay + archaea = … Sharkaea?

Brendan and Peter have started analysing the DNA of microbes from WA’s Shark Bay. These are bacteria-like beings, called archaea, are hidden in rocks and soil. So far, they’ve assembled the DNA of over 100 new microbes that use sulfates, nitrogen and carbon.

It’s been less than a decade since these creatures were first observed. Now they’re being discovered across the planet.

Hidden in the world’s airless pockets, they lie waiting for the day Earth’s oxygen disappears and they can rule the world once more.