Buried in the massive scale of data are nuggets of astronomical gold waiting to be discovered.

That’s where Ryan Ridden-Harper comes in.

As part of his PhD at the Australian National University, Ryan developed a computer program to sift through archived data from the Kepler space telescope, which was retired in 2018.

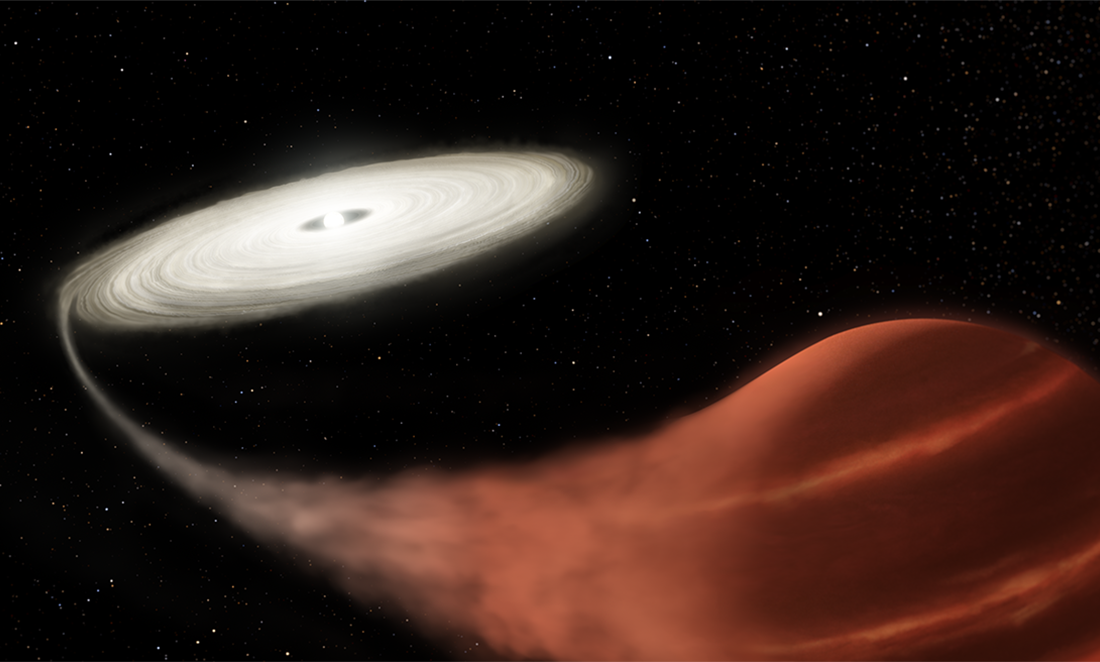

He’s already found a ‘vampire star’, but he’s most interested in extragalactic transients.

Extragalactic transients include the explosive death of massive stars or objects colliding that cause supernovae.

“Things that blow in galaxies far away from us,” explains Ryan.

Ka-boom!

Using a computer to search through big data wasn’t as easy as a few clicks.

“The real challenge was that we had no idea what, where or when in the data we were going to find something,” says Ryan.

Ryan had to set parameters for what counted as something of interest.

Like a house hunter might limit their search to cost or location, Ryan narrowed his search to light signals of a particular brightness and length.

Ryan’s computer program code can detect a wide variety of phenomena.

They include explosions, stars, asteroids, stellar flares and anything that causes an increase in brightness.

“At the end of this project, we should have a complete list of all those transient things that occurred in Kepler, which will be useful to astronomers across the world,” says Ryan.

Big, big data

Kepler’s K2 mission alone produced upwards of 10 terabytes of data. That’s more than 10 jam-packed iMacs.

If you imagine 10 iMacs full of high-resolution images, Ryan isn’t glancing at each picture. He’s combing through each pixel.

“I’ve had access to very powerful computers at the Australian National University but unfortunately it’s only going to get worse,” Ryan says.

“The next set of data we want to look at is significantly bigger.”

Big impact on astronomy

While the scale of the data gathered by the Kepler telescope is vast, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) is described as “the largest science facility ever built by mankind”.

The SKA is an array of telescopes that add up to a single lens the size of a square kilometre. Such a big lens can see a lot.

Andreas Wicenec, Professor of Data Intensive Research at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, says the SKA will gather a “phenomenal” amount of data.

“When it is fully operational, it could potentially bring in 100 terabytes of data per second,” says Andreas.

“Even the currently planned Phase 1 will already collect about 1 terabyte per second.”

The archived data of Phase 1 of the SKA could amount to 300 petabytes a year. That’s enough data to fill 300,000 iMacs.

“The SKA will be looking for multiple things, but many discoveries could hide in 300 petabytes of data,” says Andreas.

Projects like Ryan’s are crucial to furthering mankind’s understanding of the universe.

“Archived data has the potential to yield more discoveries than the initial goals of an observation project,” says Andreas.

Meanwhile, back on Earth …

Unfortunately, Ryan’s next project won’t necessarily be any easier than the Kepler project.

Each set of data has its own quirks and flaws that need to be resolved before he can trawl through the data, but he’s enthusiastic about the benefits.

“Being able to find these things is pretty exciting and valuable for science,” says Ryan.

“Hopefully this is just the start … we’ve already noticed some other interesting objects in the Kepler data that we’re still following up on.

“I’ve got my fingers crossed that there will be some crazy object floating around in the Kepler data for me to find.

“The vampire star will hopefully be just the first of many.”