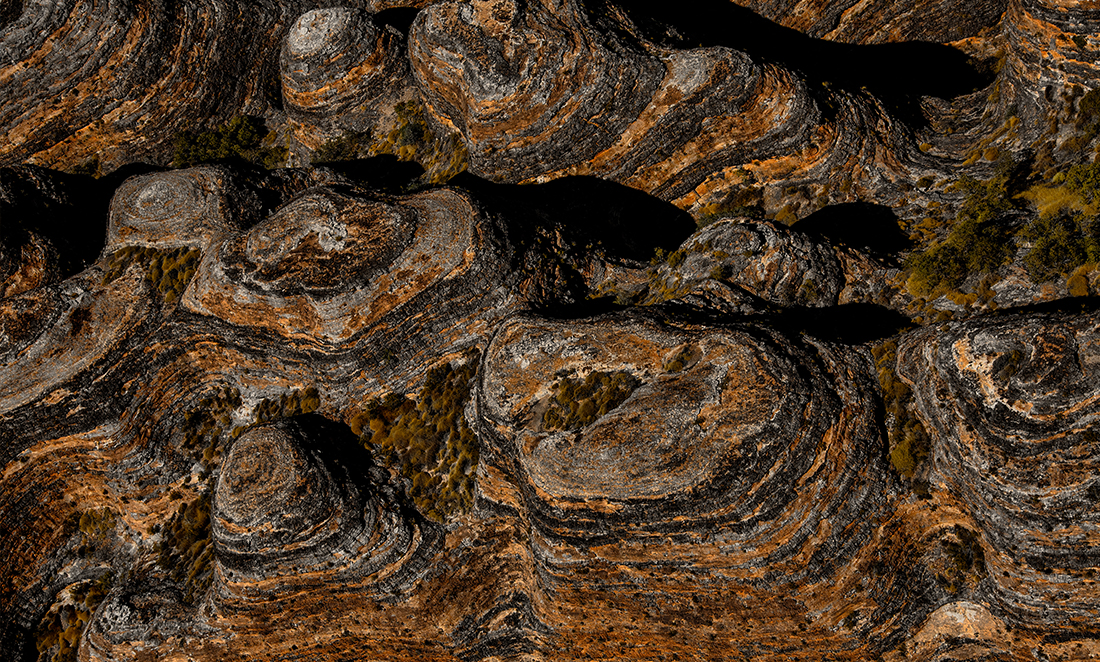

The story of the Bungle Bungles begins about 360 million years ago with a river not so different from the Ord River that flows nearby today.

That river flowed downhill towards the ocean until it hit a broad low basin. There, it spread out, slowed down and deposited its load of sediment before drying up.

Every wet season and every flood, the river left the sand and stone it carried behind, layer upon layer.

STRANGE AND FANTASTIC FORMATIONS

After a few million years, the landscape shifted upwards. The plateau formed mountains and hills, and the river began to flow downstream again.

After megayears of adding new layers, the rivers began to take them away. In that time, the earliest layers buried kilometres below the surface had become sandstone.

But unlike regular sandstone, the Bungle Bungles are held together by nothing but pressure.

“If you reach out and touch them, you’ll feel sand coming away at your fingertips,” says Chris Done, Chairperson of the Purnululu World Heritage Committee.

“The grains of sand are held together by their own pressure on each other. There’s no cementing,” he explains.

(That’s the stuff between the grains that helps them stick together.)

“They’re just pressed down with enough weight above them that they’re forced together.”

There’s some debate among geologists about just how this happened. Some think that the rock formed with cementing and later lost it, while others think it never had cementing at all.

However it formed, once that soft sandstone was uncovered, wind and water carved through it easily. A surreal landscape reflecting the twisting paths of rivers and streams emerged, and the layers deposited years ago were exposed to the elements.

As Edward Hardman, the first European geologist to encounter the formation, described it:

“The prevailing nature of the rock, however, is that of a yellow or reddish freestone, very soft in places, and susceptible to ‘weathering’, owing to which the rock-masses often assume strange and fantastic forms.”

The hills are alive

Once they were exposed, each layer reacted differently.

Layers slightly richer in iron developed a rust-coloured red colour, as the iron percolated through to the surface and oxidised.

Other layers, richer in clay, were able to hold onto more water. These became home to colonies of dark-coloured cyanobacteria, sometimes called blue-green algae.

“Those algae are about some of the toughest lifeforms you can think of,” Chris says.

“They go dormant when it’s dry, and they thrive when it’s wet.

“If you go up there when it’s been raining, it’s a shiny deep green or black, whereas during the dry season, they’re more of a grey colour.”

So while the layers run throughout the hills, the stripes are only visible on the surface. Underground, it’s pale sandstone all the way through.

Nothing but footprints

As well as giving the hills their striking colours, the protective crust of iron and bacteria slows erosion of the sandstone.

So without their distinctive appearance, the Bungle Bungles may not have endured the forces of nature for so long.

But are the stripes attracting a new force of erosion? As more and more tourists explore the spectacular site, could their feet crush the Bungle Bungles back to sand?

Humans have visited and lived in Purnululu for thousands of years. Aboriginal people hunted and traded in the area long before tourists arrived.

They recognised the range as a site of great significance long before it was World Heritage listed, and Rangers from their descendants still live in and care for the area.

They think an increase in tourists isn’t an immediate threat “as long as people do the right thing and stay on the trails”, says Chris.

So if you visit the Bungle Bungles, stick to the path and let the stripes do their job. With care, they’ll still be amazing us for megayears to come.