In the 13th century, a mapmaker toiled away in the German convent of Ebstorf, painting the known world on stitched goat hide.

Along the map’s edges, where the known world ended, dragons and fanged creatures were painted. The message was clear: here be monsters.

Hundreds of years later, the cultures of the world met, and those fanged monsters morphed into new continents.

But beyond Earth, monsters still lurk.

These monsters measure their lives in aeons, eating stars and birthing galaxies.

They exist on our maps as unfathomable black stains: here be black holes.

Monster hunter

You could call Kathryn Ross a monster hunter. She studies black holes at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR).

She is part of a team that found that the supermassive black holes at the heart of galaxies seem to be breaking the laws of physics.

Some of the 21,000 galaxies they measured were acting strangely. The light of 323 galaxies changed too quickly, while 51 galaxies were changing colour when they shouldn’t.

“We didn’t expect to see any of this. We were checking two datapoints across 2 years for these galaxies. We all just looked at it and went oh … OK?”

A long black and a doughnut

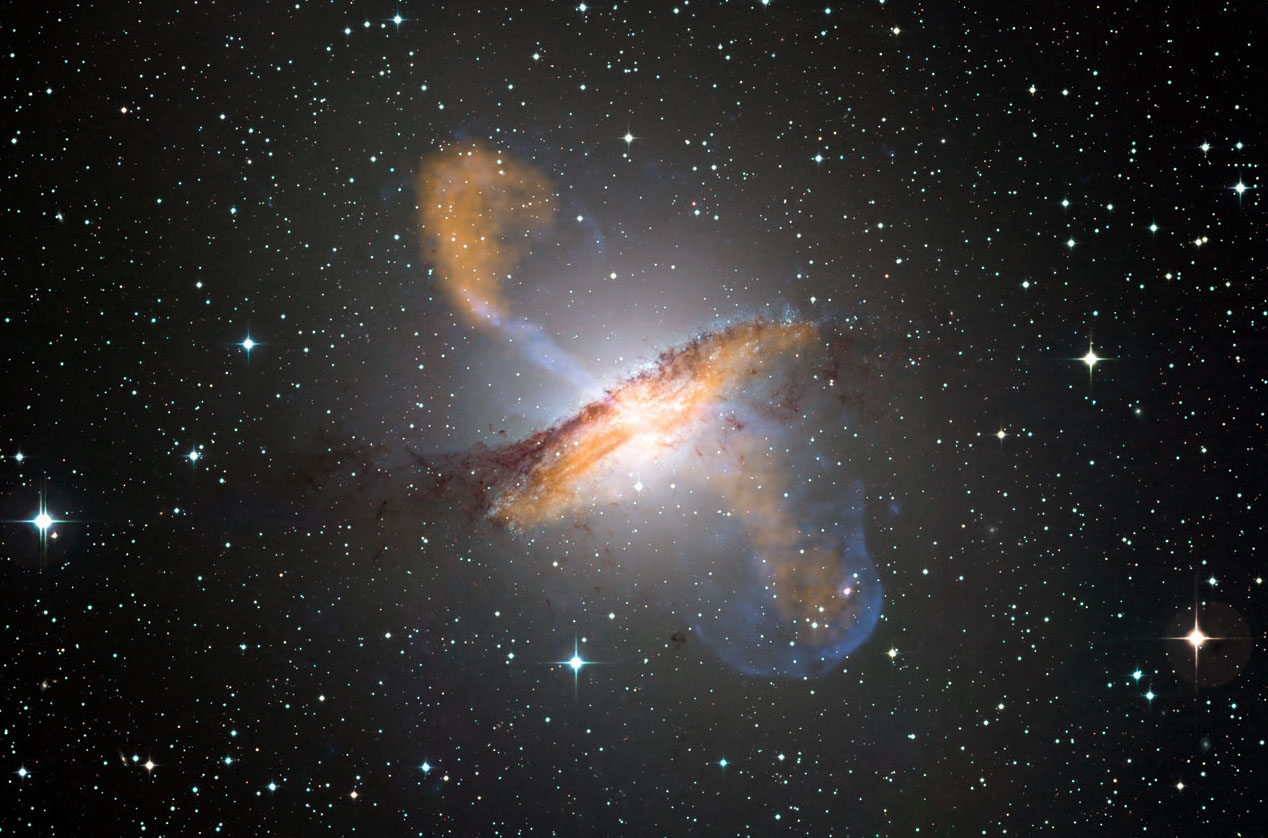

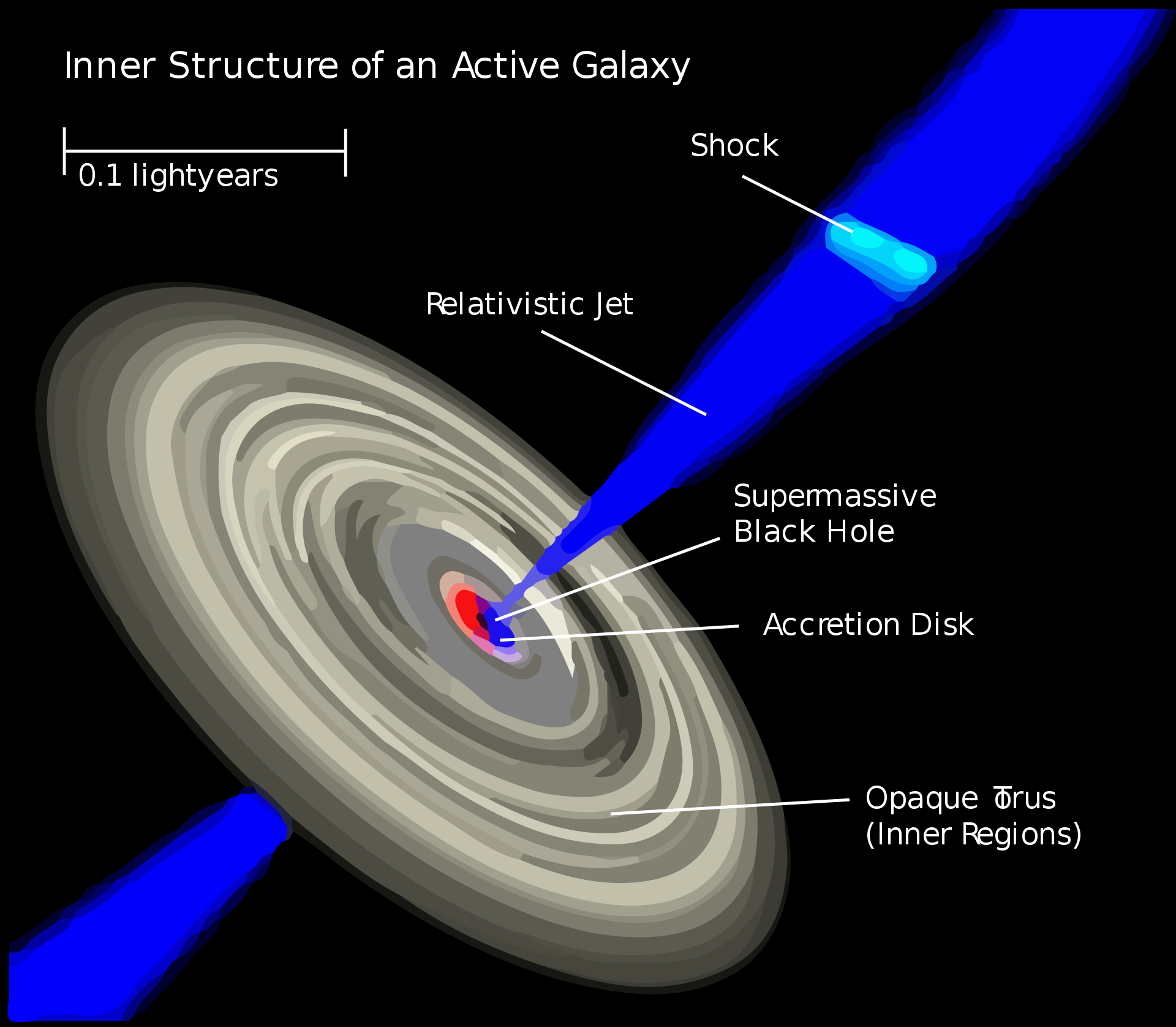

A black hole is surrounded by “a doughnut of hot plasma” called an accretion disk.

The gravity of a black hole is so powerful that anything caught in its pull would have to travel faster than the speed of light – the speed limit of the universe – to escape it. The disk is the white-hot matter being pulled apart by the black hole’s gravity.

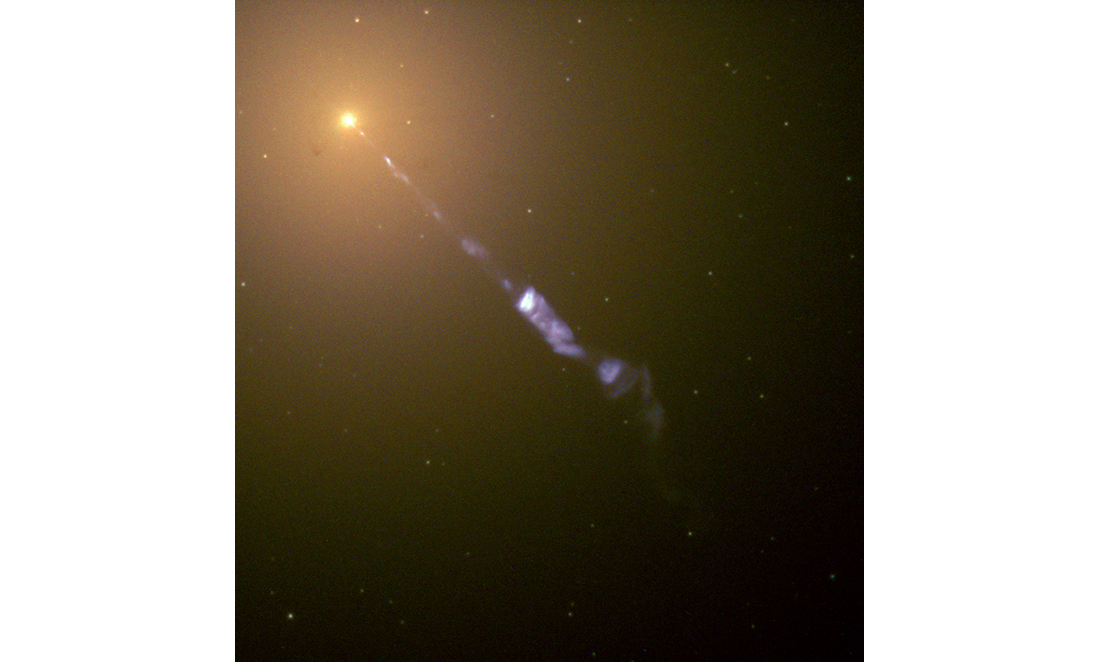

This disk will sometimes shoot powerful jets of matter and energy, like a valve releasing pent-up pressure.

These jets are constantly fed with matter from the black hole’s disc. Matter shot from these jets whirls through space, creating immense magnetic energy, along with the most powerful gamma rays and X-rays in the known universe.

This energy travelled across the universe to Earth, a riddle for Kathryn to unwrap.

White spiders, red earth

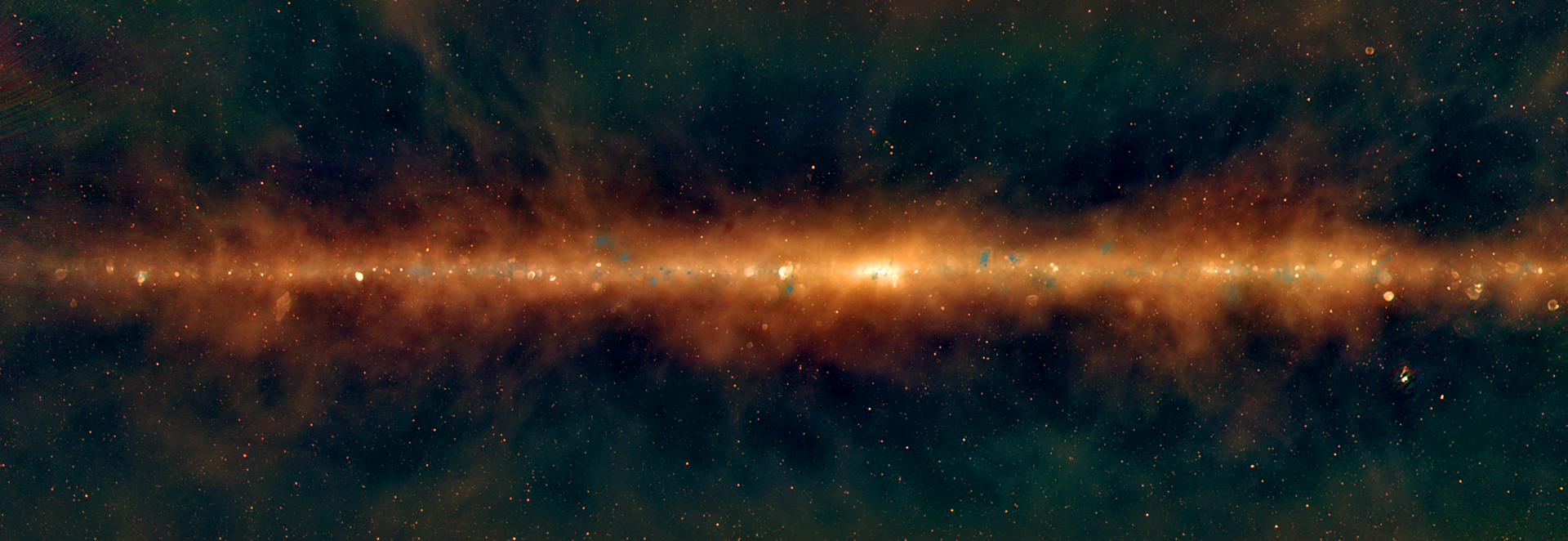

At the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA), hundreds of white antennas stand atop ferric soil.

“They look like metal spiders sprinkled across the Australian outback. They don’t actually look like they’re doing anything. There’s no moving parts,” says Kathryn.

But these antennas are passively picking up the radio signals from the jets’ whirling, burning matter.

That data runs along a 700km fibre optic line to Pawsey Supercomputing Centre. There, it’s translated into colours we can see, mapped to the strength of the radiation and its wavelength at each point in the sky.

It’s a computer the size of a room doing paint-by-numbers.

This map is called GLEAM, and it shows some galaxies changing wildly – faster than should be possible under the known laws of physics.

This is how Kathryn caught the black holes misbehaving.

“The MWA is a low-frequency telescope. It captures the coolest parts of the jet, the enormous mushroom structures far from the jet’s core.

“They’re so big you shouldn’t see anything changing. We predicted these images to be very calm – but some of them weren’t.”

Here’s where the hunt began.

Starlight, burn bright

Astronomers try to make sense of a universe that we still know very little about.

“In radio telescopy, all the radio waves we collect from galaxies are so low energy, it’s equivalent to a handful of rocks falling to the ground,” says Kathryn.

And the distances between galaxies are so huge, we can’t just go over and check when something’s acting strange.

Even the most powerful creature in the universe – a supermassive black hole – has to play by the rules.

So, if they’re not breaking physics, how could these galaxies be sparkling so rapidly?

Kathryn and her colleagues at ICRAR came up with three possibilities.

First, by pure luck, we’ve caught a bunch of black holes as they’re burping – releasing several solar systems worth of matter and energy at once.

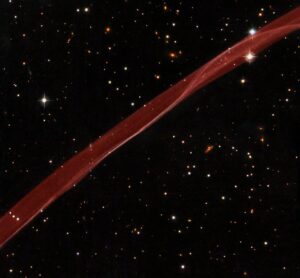

Second, it’s possible that the radio waves from these jets are scintillating as they hit huge gas clouds somewhere between us and them. This is the same physics that makes stars twinkle when gases from our atmosphere pass between us and the star’s light.

Or third, Earth is being hit by a blazar, meaning the black hole’s jet is targeted directly at us. On a smaller scale, neutron star jets have been recorded varying wildly in colour and brightness. These black hole jets could be doing something similar on a scale over a billion times larger.

Twinkle twinkle little star-eater

So which one is it?

“As a scientist you’ve got your hunches,” Kathryn said.

“My two favourites are scintillation and blazars.

“The problem is with the galaxies that change colour. Scintillation changes brightness but not colour.

“In those cases, it could be a number of things, but blazars seem the most likely.

“We’re looking right down the barrel of the gun of these jets, and we’ve seen similar changes on smaller scales with binary system black holes.”

Like many scientific discoveries, this journey didn’t start with “Eureka!” but with “That’s weird …”

The discovery of these twinkling black holes might have been an accident, but now she’s caught them, Kathryn’s collecting data to figure out which possible answer is the real thing.

But even with these answers, black holes remain mysterious. These behemoths swallow solar systems, warp space and test the limits of known physics. The centre of their insatiable maws are still dark spots for humanity, places we can never go and may never fully understand. So these great beasts continue to stalk the edges of our maps: here be black holes.