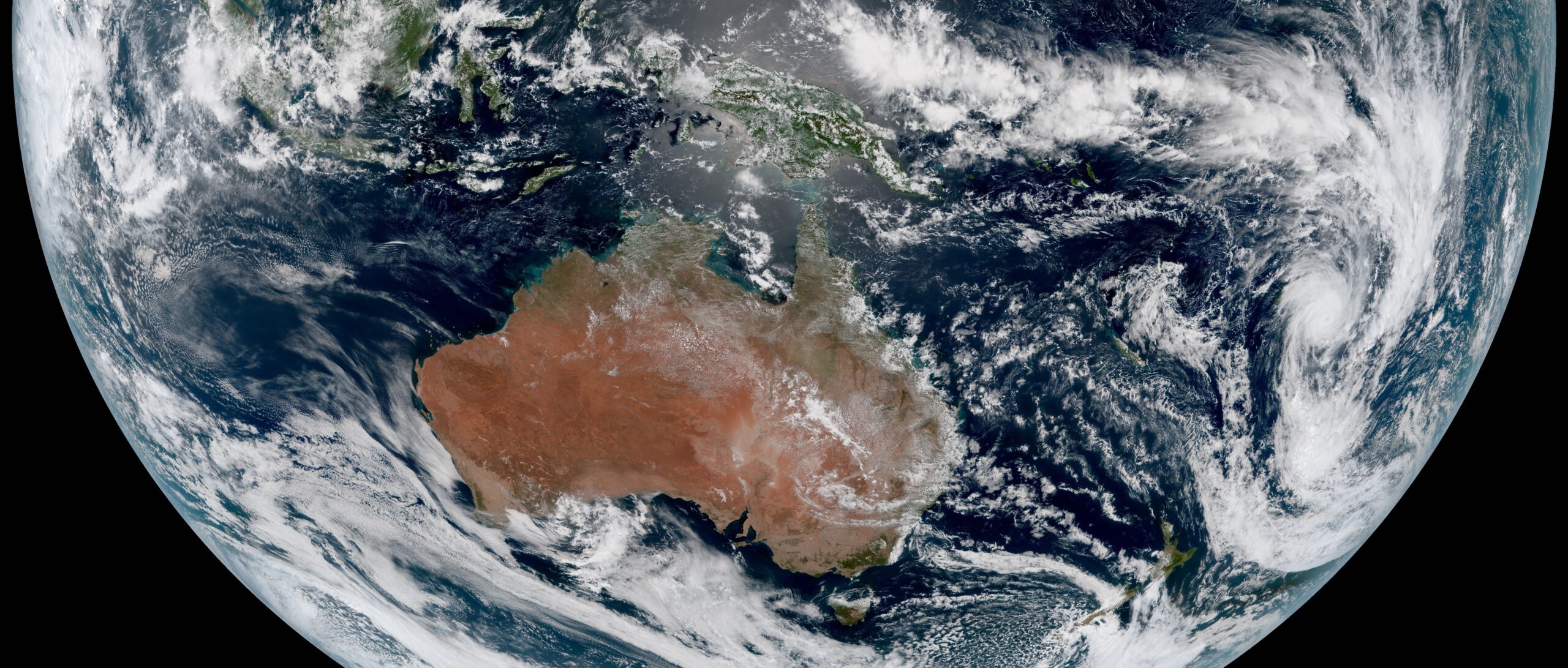

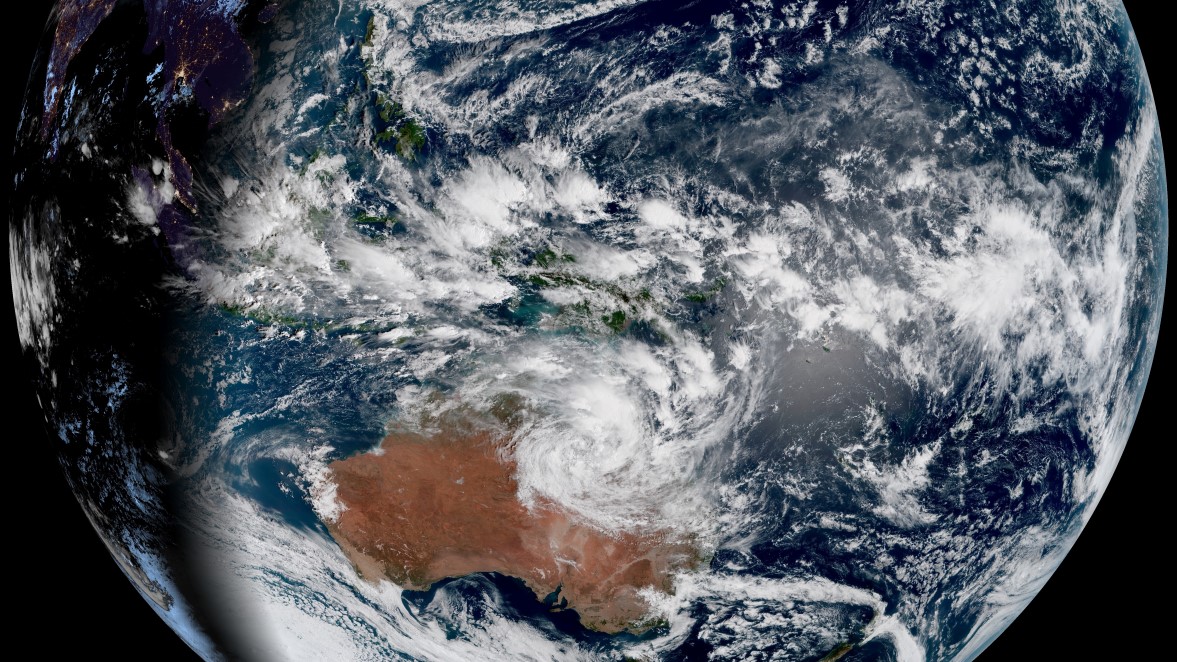

Let’s take a look at how an image you might see every day—a satellite picture from the Bureau of Meteorology—gets from outer space into your hands.

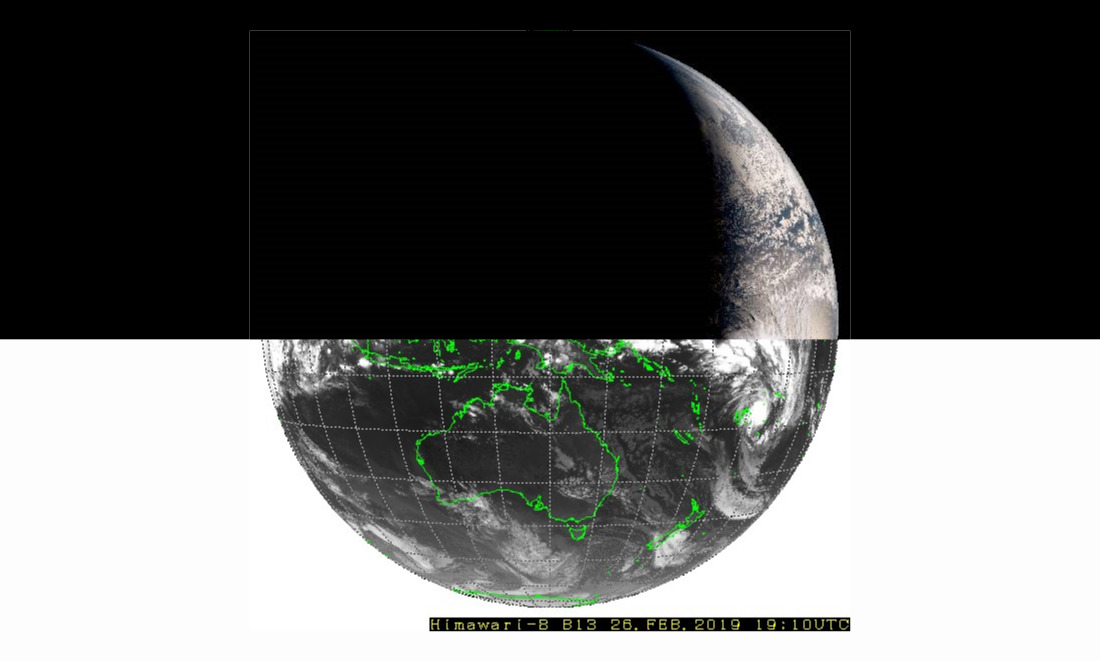

“Most of our satellite images come from the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Himawari-8 and Himawari-9 satellites,” says Chris Griffin from the satellite applications group at the Bureau of Meteorology.

“So the first thing our image has to do is cross the 35,000km of space between us.”

These satellites aren’t just a webcam in space—their multispectral imagers take a picture capturing an entire side of the Earth every 10 minutes.

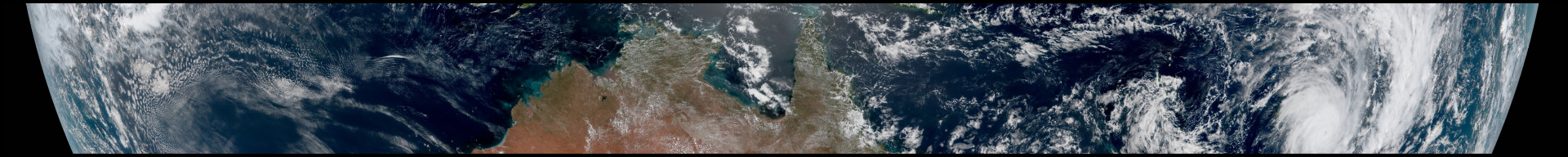

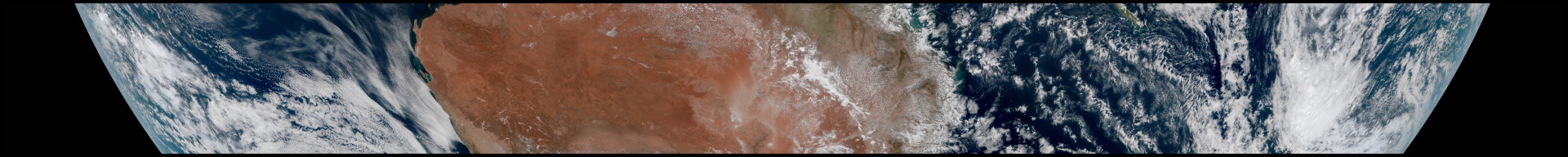

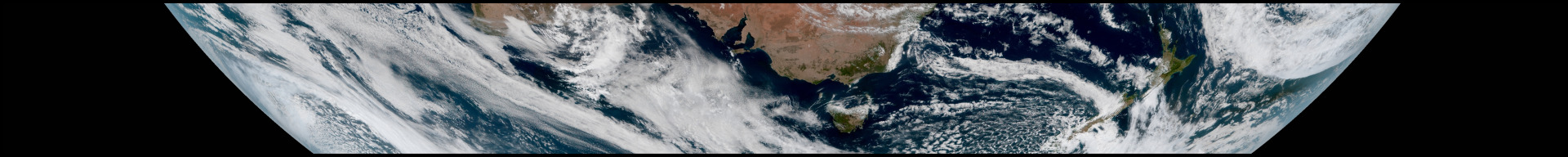

But unlike a regular camera, it doesn’t take the picture in a single snap. Instead, it scans back and forth across the planet (a bit like an old-school TV), building up the image in 10 long chunks before beaming them down to a ground station in Japan.

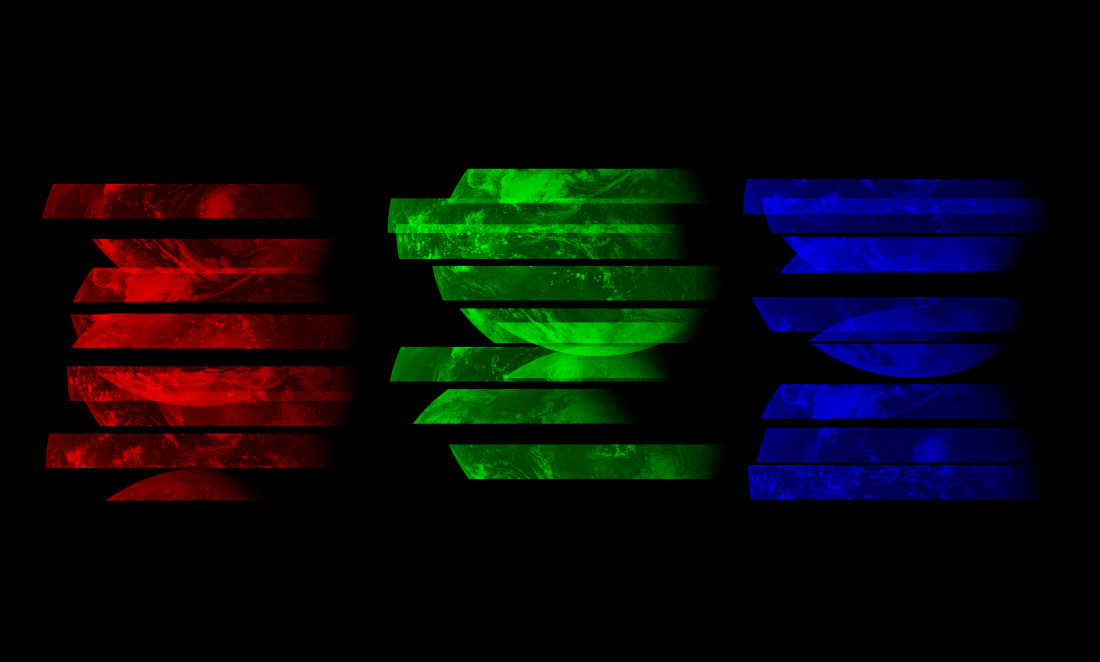

The picture isn’t just sliced into strips—it’s also split into its component colours too. The final picture we see is made up of a combination of red, green and blue pixels. Up in the satellite, a separate image is taken for each visible ‘channel’ along with other invisible colours like infrared.

When our satellite image arrives in Japan, it isn’t the square photo you’d expect to see. Instead, a string of colourful stripes make up a psychedelic jigsaw that needs solving.

Putting the puzzle together

These pictures are big: each pixel represents about 1 kilometre on the ground. We’re dealing with an image thousands of kilometres across, where a few pixels could mean the difference between a storm hitting a city or passing by.

Putting it together is a bit of a challenge too—not only do we need to line up all our strips and stack up all our colour channels, we also need to line this picture up with the last one, so we can compare the changes over time.

And to top it off, we’ve got to do all of this in under 10 minutes, because that’s when we’ll have to start again with the next image.

That’s way too much for a human forecaster, so meteorologists use a supercomputer instead. It solves this puzzle the same way we would—by looking for features and landmarks on the surface and making sure they line up.

It might sound easy, but remember, the reason we’re taking this picture is because it’s covered in moving clouds—there’s no guarantee that any given landmark is going to be visible!

Blue skies and dark nights

Once it’s been stitched together, Japan sends three copies of the image to Australia—one through the internet, another using a communications satellite and a final copy via a custom high-speed cable connecting both countries.

But before the image can be used, the Bureau of Meteorology has a couple more things to do before they can upload our clouds to the cloud.

When we look up from the Earth during the day, we see a blue sky. When we look down from space during the day, we still see that blue sky, only now that blue sky is between us and the Earth.

“Every image that comes off the satellite is very slightly blue,” says Chris.

“We basically have to try to figure out how much atmosphere is between us and every feature—whether that’s a cloud or a surface feature—so we can calculate the impact of the colour of the sky.”

That gets our colours right during the day, but what about at night when there’s no light?

This is where some of our hidden colours come in.

Alongside those red, green and blue pictures, the satellite also captures infrared light.

Anything warm—the land, the sea and, yes, even the clouds above us—glows with infrared light. We can see the clouds at night, but with a bit of a twist.

The colours we see in these night images don’t represent the real colours of the clouds. Instead, they represent how bright a cloud is glowing in infrared—or how much glow it’s blocking from the ground. It’s like Predator vision for the entire planet.

Time to show off

After it’s stitched, aligned, coloured and corrected, our image is finally finished.

Less than 10 minutes after it’s received in Japan, it’s published to the Bureau of Meteorology’s Satellite Viewer for everyone to admire—just in time for the whole process to start again.

But these images aren’t just pretty, they’re practical too.

They let forecasters measure temperature and movement of air in our atmosphere, watching how clouds move and change over time. We can see smoke, dust and water vapour using those infrared cameras—all useful for human forecasters to improve their models and figure out what’s happening in the atmosphere.

“There’s so much data and it’s coming so quickly,” says Chris. “This is really only scratching the surface of what we can do.”

So next time you check the weather, take a moment to appreciate how much work goes into what you’re seeing—and just how cool it is that we get to experience this amazing view of our planet every day.