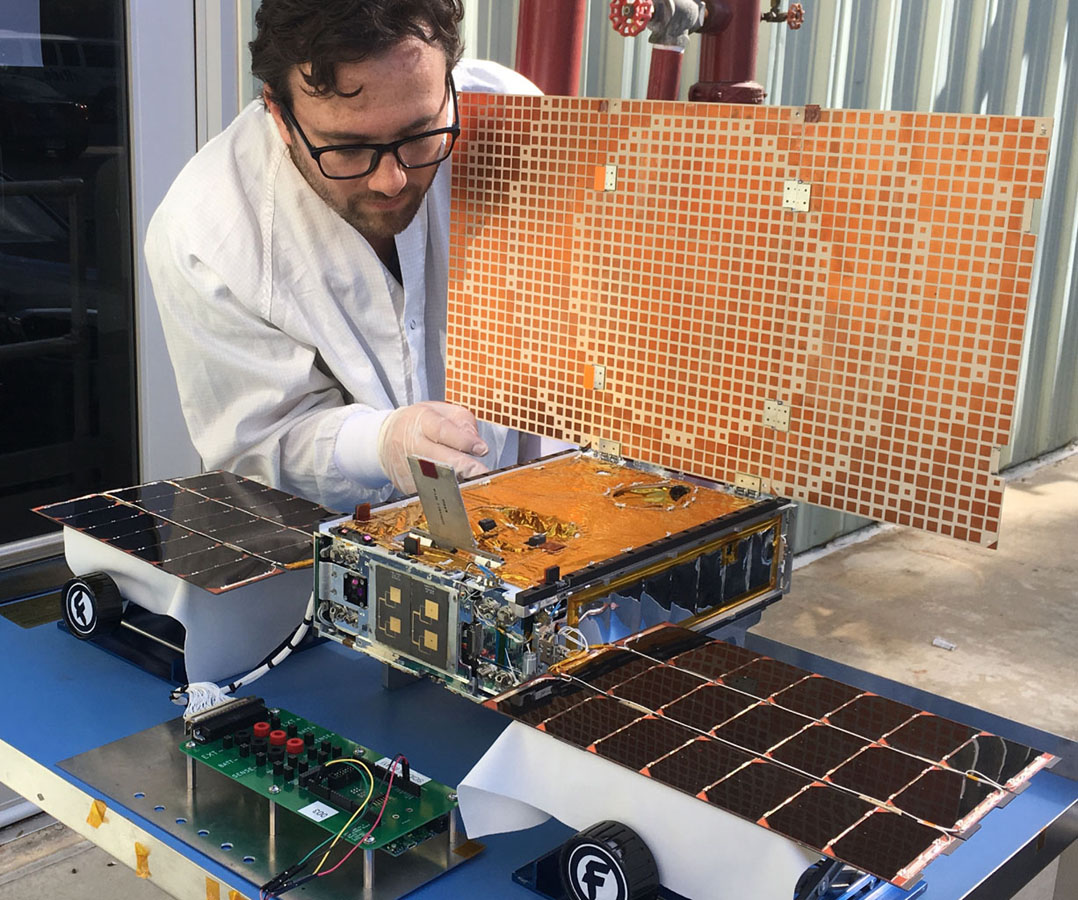

In case the name hasn’t given it away, CubeSats are small, block-shaped satellites.

These mini-satellites only measure 10 centimetres a side and weigh around 1.3kg. They can be used for a wide range of jobs, and some even fit together to make larger satellites—sort of like a set of cosmic LEGO bricks.

Compared to a normal satellite, CubeSats can be a thousand times lighter and smaller, especially when compared to the likes of the Hubble Space Telescope.

The idea behind these little boxes is pretty simple. Sending things into space can cost millions of dollars. It’s so expensive, spaceflight companies try to minimise wasted space on their rockets.

Sometimes, a larger satellite leaves some spare room on the rocket, and CubeSats can fill that space. Compared to the huge costs for a separate launch, a three-unit CubeSat can get orbital for around $240,000.

CubeSats in action

Because of their low cost and versatility, these tiny satellites are great for research.

Last year, the CSIRO started building their own CubeSat with a suite of infrared sensors called CSIROSat-1. The data collected will be valuable for tracking fires and studying the formation of clouds and tropical cyclones.

But CubeSats aren’t only good for research.

Myriota is an Adelaide company using CubeSat technology as a remote monitoring solution. Their sensors communicate with orbiting CubeSats every 90 minutes, sending data to a phone or computer.

This helps their customers stay up to date on things like location data, water levels and pump pressure on remote sites.

Australia in space

The Australian Space Agency (ASA) has governed the launch of CubeSats in Australia since it was set up in 2018.

Only a few months after ASA’s formation, Australia’s Space Activities Act received a major amendment, making it easier for small companies to launch satellites in Australia.

Deputy Head of the ASA Anthony Murfett says Australia plays an important role in the international space industry. And it all comes down to our ability to track satellites in the southern hemisphere.

“We’ve got a wonderful location in the southern hemisphere,” says Anthony.

“There are more objects in space and people need to access that information, which means ground stations to communicate with CubeSats. We can use imaging technology and space situational awareness to monitor what’s in orbit.”

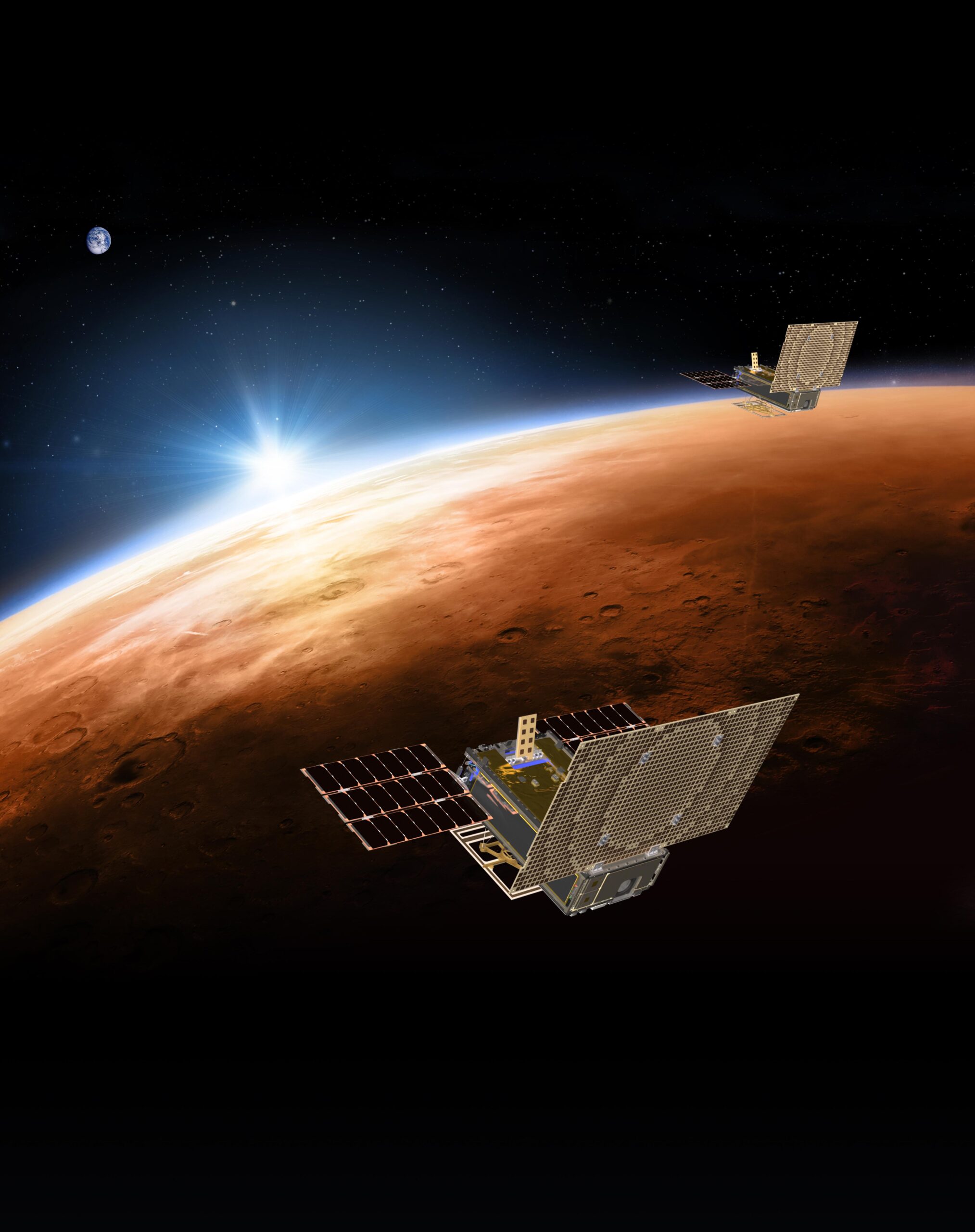

CubeSats on Mars

Most CubeSats can be found in low Earth orbit, which is the area 160 to 2000 kilometres above the Earth’s surface. However, some CubeSats find themselves a long way from home.

NASA’s InSight mission to Mars is the first time we’ve focused on the Red Planet’s deep interior. When InSight pulled into orbit, it brought two CubeSats along for the historic ride, helping to communicate back to Earth.

Called MarCOs, the six-unit CubeSats measure only a few centimetres. Yet they’ve been communicating across the 200 million kilometre divide between the planets.

The MarCO CubeSats have proven it’s not the size of the satellite that counts but how you use it.