Artificial intelligence (AI) systems used for facial recognition are notorious for their racial and gender bias. The lack of diversity in the photographic data used for AI training is usually highlighted as the root cause. Well, it turns out that the human brain has the same problem – and we don’t really know why.

The own-race bias is a phenomenon where humans struggle differentiating between individuals of another race. It’s been researched for decades but the scientific jury is still out on what the true cause of the phenomenon is – because we’re still trying to understand the finer details of how the human visual system works.

“If what we’re trying to do is to predict whether something is likely to be visible or not, then we’re pretty reliable at that and we can do that taking into account a fair range of clinical disorders.” says Winthrop Professor David Badcock, Director of the Human Vision Laboratory at UWA.

“There are other things which seem incredibly fundamental and profound, which we still can't explain.”

And the phenomenon of own-race bias is one such fundamental question that is yet to be answered.

Level up

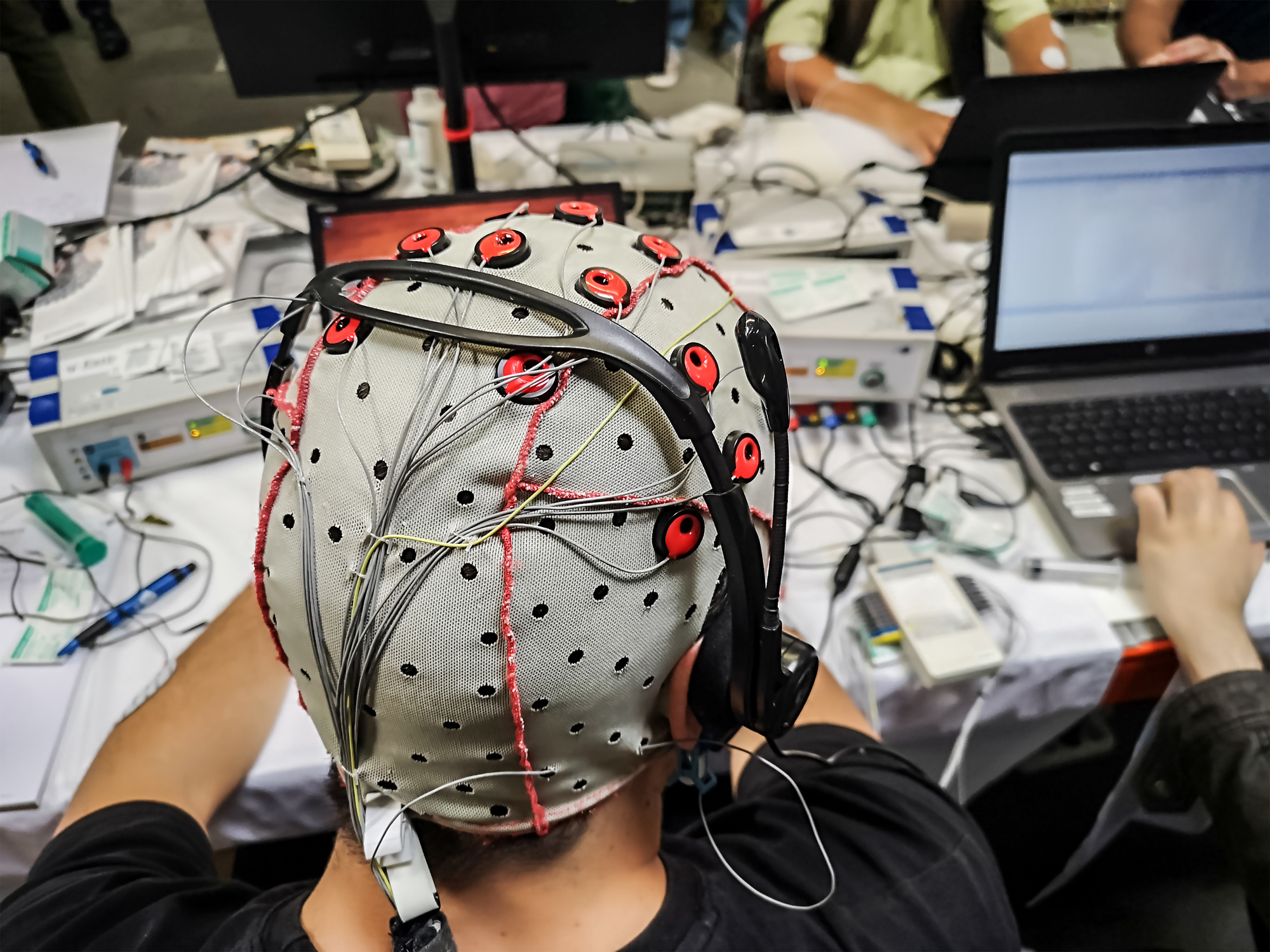

From the instant light rays enter your eye, millions of cells interact with each other to process the information and turn it into an action. To fully understand vision, we need to understand every step of that process.

“You’ve got multiple stages of processing, which all feed information forward,” says David.

“And in each of those stages there’s also feedback that comes back from higher order areas [of the brain] to low order areas, which influence the way the lower areas process.”

So far, researchers know that the early stages of the visual system can only process very small bits of information because there’s a limit to what one single cell can do. One cell can detect only a tiny fraction of the object that you’re looking at.

Somewhere in the middle, David says, our brains put those fractions together into objects.

“They put together the information from the lower levels into groups and say, right, well, that’s all one object. And that’s all another object,”

Later in the visual system, our brains work out what those groups of things actually are.

“The difficulty is connecting one level to another,” says David.

So scientists are still trying to figure out the exact rules our brain use to process visual information through the different levels. This is where AI could help.

A potential path

One way of doing it is to build a computer simulation that has the same sort of stages that the human visual system does. Then, researchers show it lots of images, and ask it to learn to identify objects in them.

“Then when that’s done, we can look at the layers of this artificial network we’ve created and say, ‘Well, what does it seem to be doing at this level?’ Which gives us a hint about what kind of information it’s using and what rules [it’s] choosing to put things together,” explains David.

And the theory is that if we build a model that’s “reasonably close” to what the human visual system is like, it will give us some information about what rules are being used by our brains.

“Identifying faces in the crowd and those sorts of technologies … if you want to learn how to do that, then you can do that without trying to copy the human visual system,” says David.

“But we want to understand how human vision does it. And so, we use the AI as a tool to try and give us clues about what would be useful, what might work,”

And hopefully, the results will finally help us understand our own visual biases too. Maybe, like AI, we just need a little diversity in the data we learn from.