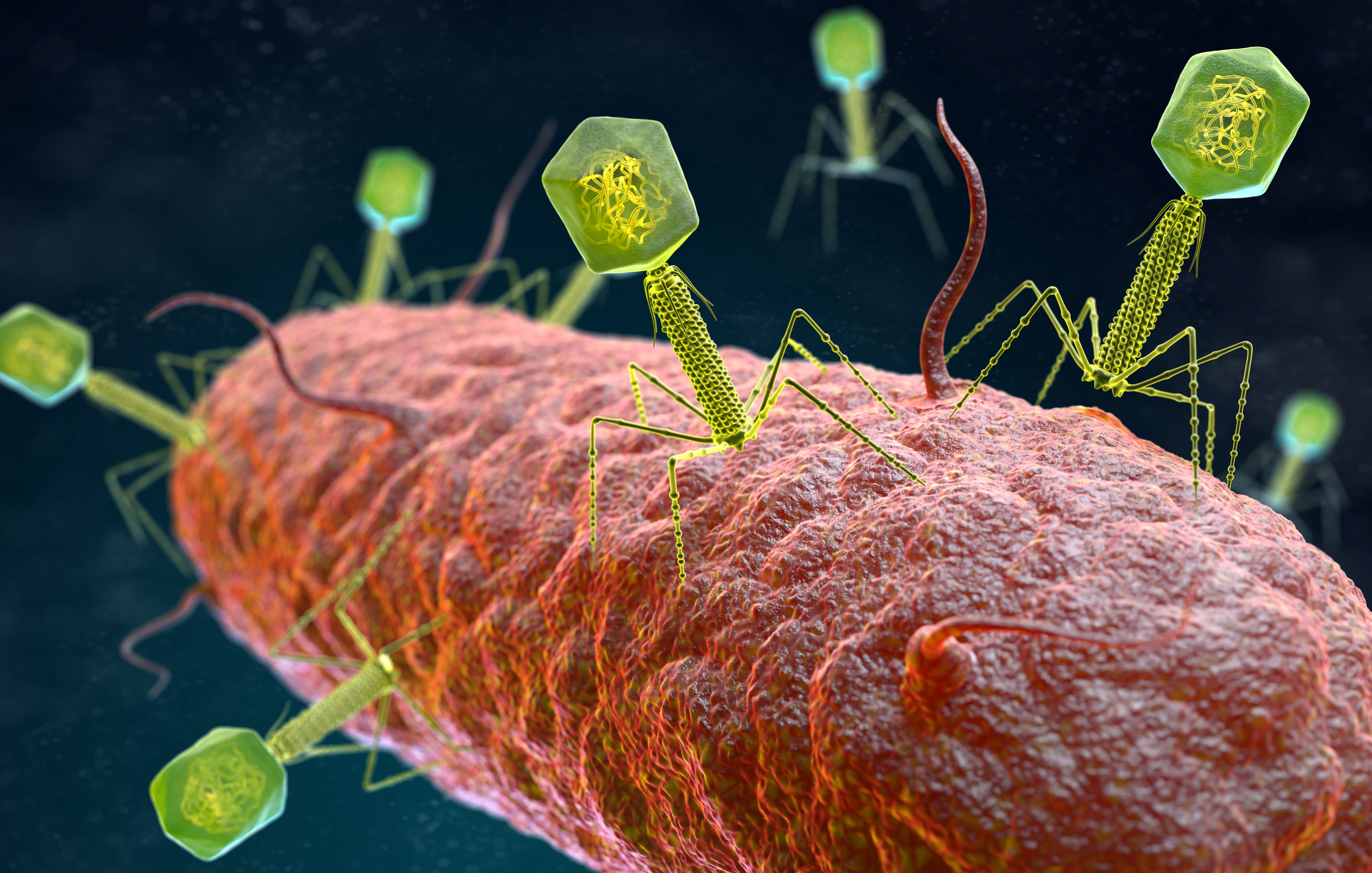

Viruses that infect bacteria are called bacteriophages, or simply phages. They are the most abundant organism on the planet.

Being natural predators, these viruses hijack bacteria and turn them into phage-building factories. The newly produced phages collect inside the bacterium until eventually the cell dies and millions of new phages come pouring out.

And it’s this bacteria-killing ability that makes phages a promising treatment for bacterial infections in humans.

Release the phages!

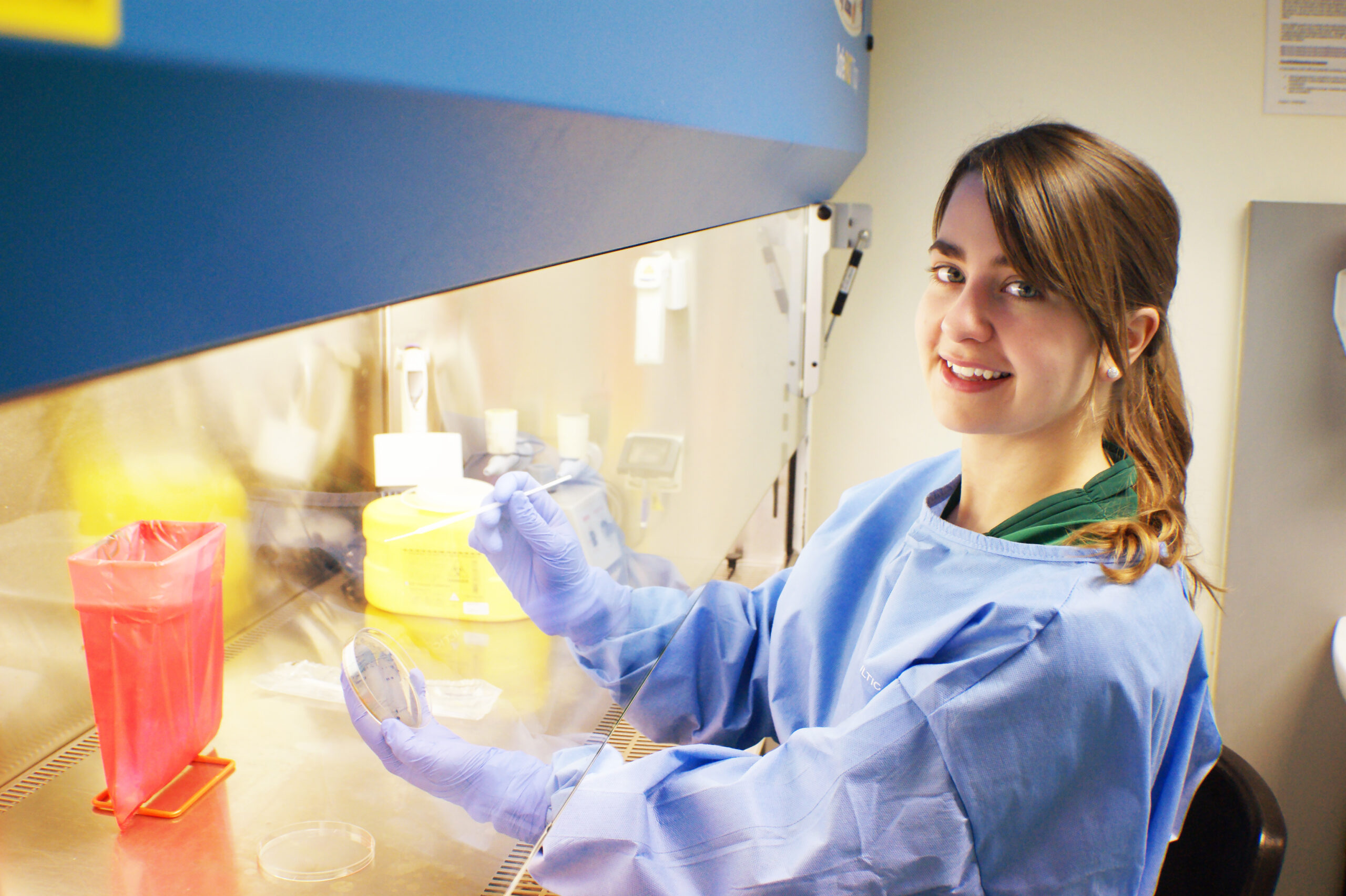

Dr Lucy Furfaro is a microbiologist at The University of Western Australia who has been intrigued by phages from the moment she learned about them.

“I remember thinking, ‘This is SO cool!’ and then ‘OK, there are viruses that can kill bacteria ... why aren’t we using them?’”

Currently, phages are used only where antibiotics have failed and there are no further treatment options left to try.

“At the moment, the use of phages to treat patients is restricted to compassionate use. You need to get special access from regulators,” says Lucy.

Robust safety and efficacy information is needed before phages can become part of routine care.

The good, the bad and the bug-ly

Currently, the go-to treatment for bacterial infections is, of course, antibiotics. Phage therapy promises two distinct advantages over these drugs.

Firstly, phages are very specific. Phages infect one type of bacteria or sometimes a very small number of closely related bacteria. Antibiotics, on the other hand, work on a much broader scale.

A single antibiotic drug will kill many different bacteria — including the good ones. This can disrupt our microbiome — the ecosystem of microbes that live on and inside of us — which can have a substantial impact on our health and wellbeing.

Phage therapy could target the disease-causing ‘bad’ bacteria without harming our good bacteria.

Phage therapy may also overcome a second consequence of antibiotic use — superbugs.

Bacteria are constantly evolving to protect themselves from antibiotics. And they can share these new abilities with other bacteria too. The result is scary – infections with superbugs can be difficult, even impossible, to treat.

Dr Furfaro: bacteriophage hunter

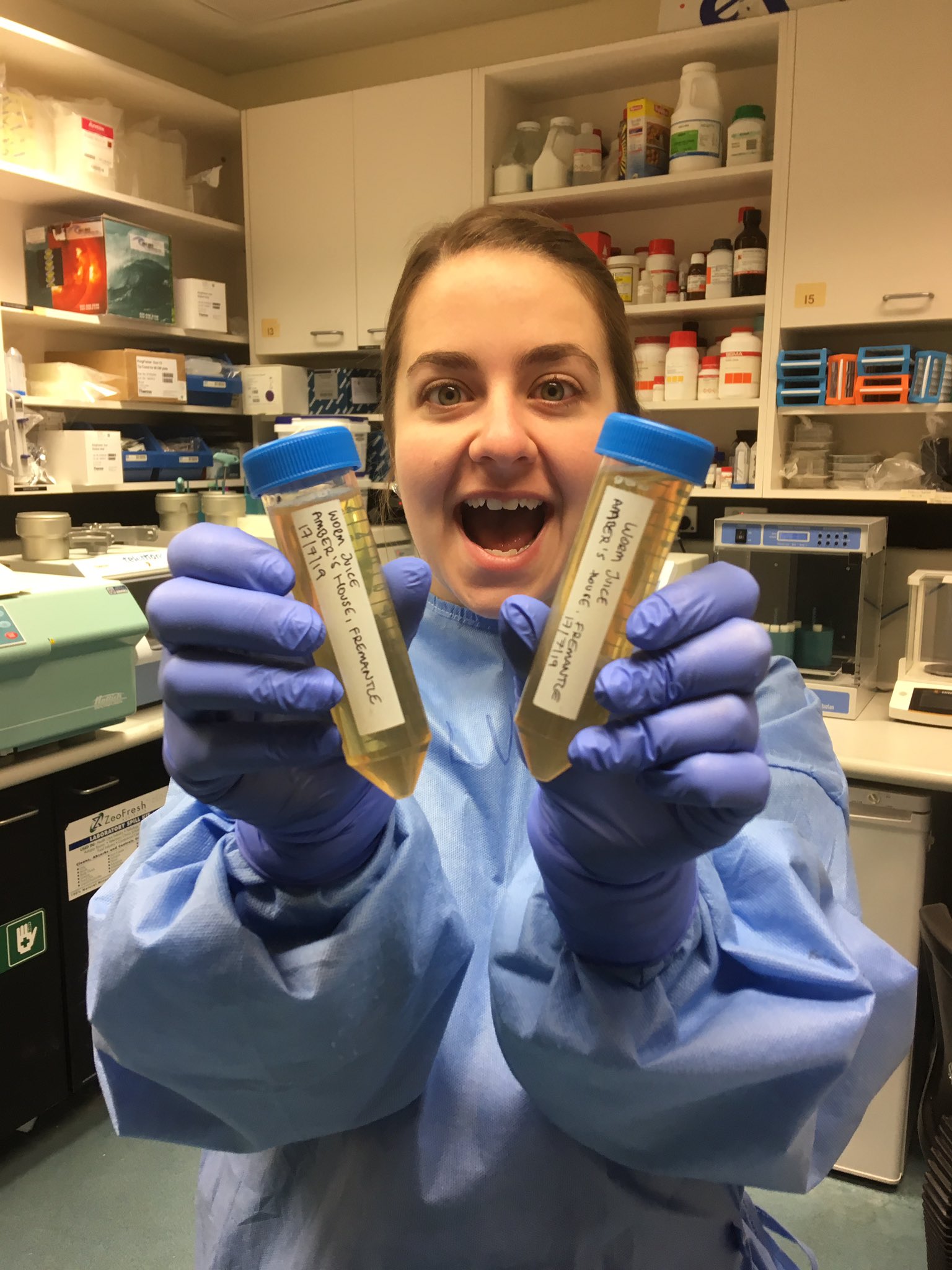

Lucy’s research focuses on understanding our natural exposure to phages. The self-described bacteriophage hunter takes samples from all kinds of environments. Her focus is on places where both the bacteria and the phages are abundant — such as household garbage and human wastewater treatment facilities.

Once back at the lab, Lucy screens the newly isolated phages for their bacteria-killing ability. This involves adding them to agar plates where bacteria are growing and seeing which of the bacteria they can kill.

Lucy understands that the idea of using phages as treatment can seem pretty frightening for some people.

“It’s just really scary to say, ‘I want you to take this virus’. I want to make sure people understand that they don’t infect human cells – they’re only infectious against the bacteria.”

By looking at all of the phages we safely encounter in our daily life, her research will help to reassure people that phages aren’t dangerous. It will also help researchers get a better understanding of how our bodies might respond to phage therapies as a new treatment option.

If the research goes well, this is one treatment option that’s sure to go viral.