In Greek mythology, a chimera is a monster that looks like a lion with an extra goat’s head on its back and a snake for a tail. It was commonly known for eating people, not saving them.

But there’s another type of chimera, and you might just be one.

Everybody has a unique strand of DNA, which is like the set of instructions that detail how your body is built. And each cell in your body has an almost exact copy of your DNA. It’s what makes each of us biologically unique individuals.

But sometimes, someone else’s DNA can get into your body and start spreading its own set of instructions – making you a genetic chimera.

The natural pathway

Chimerism can occur naturally or as a result of a medical procedure.

While 10% of humans are thought to be chimeras, only about 100 cases have been documented.

Natural chimerism can happen in the womb when blood cells from the mother and the child mix despite the placenta trying to keep them separate.

When this occurs, the mother’s postnatal body might have one cell from her child for every 10 million cells of her own. And since cells reproduce, the ratio might stay this way for years after pregnancy.

Cells can also be shared between twins while they’re in the womb. In fact, non-identical twins can have copies of each other’s cells for decades after birth.

The medical pathway

Blood or organ transplants are one of the most common ways you become a chimera. This is because blood and organs are made up of cells that contain the donor’s DNA.

For organ transplants, this will eventually lead to organ rejection of varying degrees, as the recipient’s body recognises the new organ as an intruder.

For blood donations, as long as you have a compatible blood type, an immune response is less likely.

Blood compatibility depends on a number of different things, but your white blood cells are one of the most influential factors.

The X-Factor

Dr Seong Lin Khaw is a paediatric oncologist at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI).

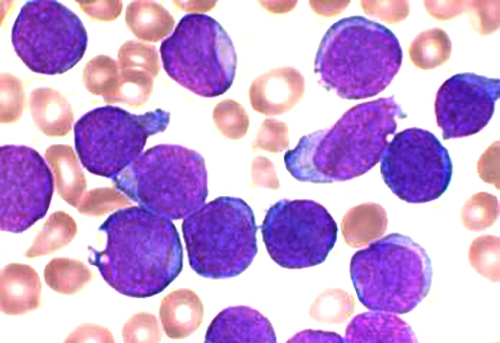

He studies acute lymphoblastic leukaemia – one of the most deadly types of cancer in children.

Leukaemia is a cancer that makes your blood and bone marrow produce mutant white blood cells. Leukaemia patients receive healthy new white blood cells via blood donations.

And by testing their level of chimerism, Seong can tell if the treatment is working.

“There’s two ways we can do it. If the donor was of the opposite sex, we can look at karyotyping – that is seeing if the number of X chromosomes are equal to what we’d expect,” says Seong.

Biologically, females have two pairs of X chromosomes, while males have an X and a Y chromosome.

So the number of X chromosomes in the blood shows how much of the donor’s blood is present.

But for same-sex donations, a DNA test is needed.

“We don’t have to analyse the patient’s full genome. Instead, we look for important repeats that act like a genetic fingerprint,” says Seong.

Focusing on key differences in blood DNA means Seong can tell if a donation has worked, sooner rather than later.

His MCRI colleague Professor Paul Lockhart is improving this test by focusing on repeating bits of our DNA.

“Genetic repeats are highly variable between donor and host, which lets you easily infer chimeric load.

“It can be automated and requires little specialist knowledge to interpret the test, making it amenable to diagnostic use,” says Paul.

So turning cancer patients into chimeras might help save them. Let’s just hope they don’t eat us!