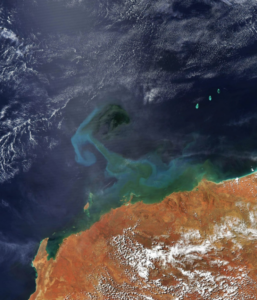

A Curtin University study of tiger snakes living in our urban wetlands has suggested that the serpents are accumulating heavy metals in their scales.

A sample of more than 100 tiger snakes from Lake Joondalup, Herdsman Lake, Bibra Lake and Loch McNess in Yanchep National Park revealed chronic contamination at all four sites.

In contrast to snakes bred in captivity, wild snakes were found to have significantly higher levels of arsenic, lead, mercury, uranium and other metals accumulating in their bodies.

Exceeding government guidelines

The research was led by Damian Lettoof, a wildlife ecologist and Curtin University PhD student, who collected snake scales and sediment samples from each site.

According to Damian, Herdsman Lake was the most contaminated. The levels of arsenic, lead, copper and zinc in the area exceeded government guidelines.

It showed in the snakes.

Damian found arsenic levels were 20–34 times higher in wild snakes from Herdsman Lake and Yanchep when compared to their captive-bred counterparts.

“Uranium was eight times higher in Herdsman Lake snake scales than captive snakes,” he says.

Catching a tiger snake

Damian has caught more than 500 tiger snakes in Perth since the start of his PhD.

And he initially tested their livers, not their scales. It was the first Australian study to show that snakes are a good indicator of wetland contamination.

“But testing livers is not really good for the animals because most of the time we have to euthanise them, or collect specimens that we find dead anyway,” Damian says.

“So we wanted to try and look at a non-lethal tissue, which is snake scales.”

To catch the snakes, Damian and his specialist team use elbow-length Kevlar gloves and pinning tools. And although it’s non-lethal, sampling snake scales is a two-person job.

“Someone’s basically restraining the head with a gloved hand while the other person flips them on their back,” Damian says.

“[We] hold them straight and just put some scissors underneath one of the belly scales. It’s basically like clipping a fingernail.”

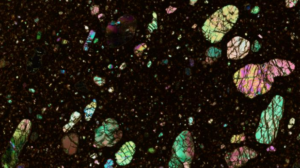

Damian tested the snake scales with a geological technique known as ‘laser ablation’.

The technique uses a specialised laser that turns everything it touches to atoms.

“[The scales are] in a vacuum-sealed box that’s basically inhaling all the atoms,” Damien says.

“And running [the atoms] through a mass spectrometer that is measuring them all as they come through.”

Top predators

Damian says tiger snakes are good indicators of wetland contamination in Perth because they are at the top of the food chain.

And they’re a good gauge of long-term, chronic contamination.

“Other research suggests they seem to be quite tolerant to high concentrations of a lot of these contaminants,” Damian says.

“And because they’ve got a really slow metabolism, it takes them a lot longer to shed and metabolise these elements.”

Damian says snakes also have a small home range.

“If you’re picking it up from one spot, that’s probably representing contamination in [about] an 800-metre radius,” he says.

Damian says the next step is to look at how wetland contamination is affecting the animals that persist there.

“You look at a lot of these wetlands and there’s still birds there, and there’s still frogs … there’s still snakes and you think it’s going fine,” he says.

“But then, we’re finding these higher levels of contaminants … it’s got to be having some effect.”