Two dangerous hospital bacteria are working together, increasing their virulence and resistance to antibiotics.

Sounds like the plot of a B-grade film, but unfortunately, as revealed in a new study from Macquarie University, it’s very much our reality.

“This is the culmination of 10 years of collaborative research into how pathogens interact with each other,” says Associate Professor Amy Cain, co-author of the new study.

“We were amazed to find that Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii work together. And when they do, they are more deadly and more resistant to treatment.”

“They each have their own specialist job – one is feeding the other, and the other is providing antibiotic resistance,” says Amy.

This discovery has significant implications for hospital screening methods and treatment options.

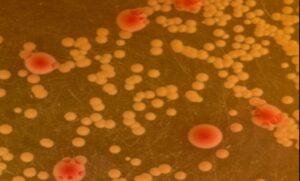

Klebsiella pneumoniae (red) and Acinetobacter baumannii (yellow) growing together on differential media | Dr Lucie Semenec, Macquarie University

Top of the list for resistance

There are six escape pathogens, or ‘superbugs’ as we know them, that form most hospital-acquired infections.

Both Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii are at the top of the World Health Organization’s list of bacteria in urgent need of new antibiotics.

Working together, these two pathogens create more biofilm – a sticky and strong protective layer. Biofilms form on implanted medical devices such as catheters and replacement implants, causing infections that antibiotics struggle to treat.

“They are really dangerous and especially dangerous for immunocompromised patients,” says Amy.

“Klebsiella pneumoniae is always around, but Acinetobacter baumannii tends to go in cycles, with some years being worse than others.”

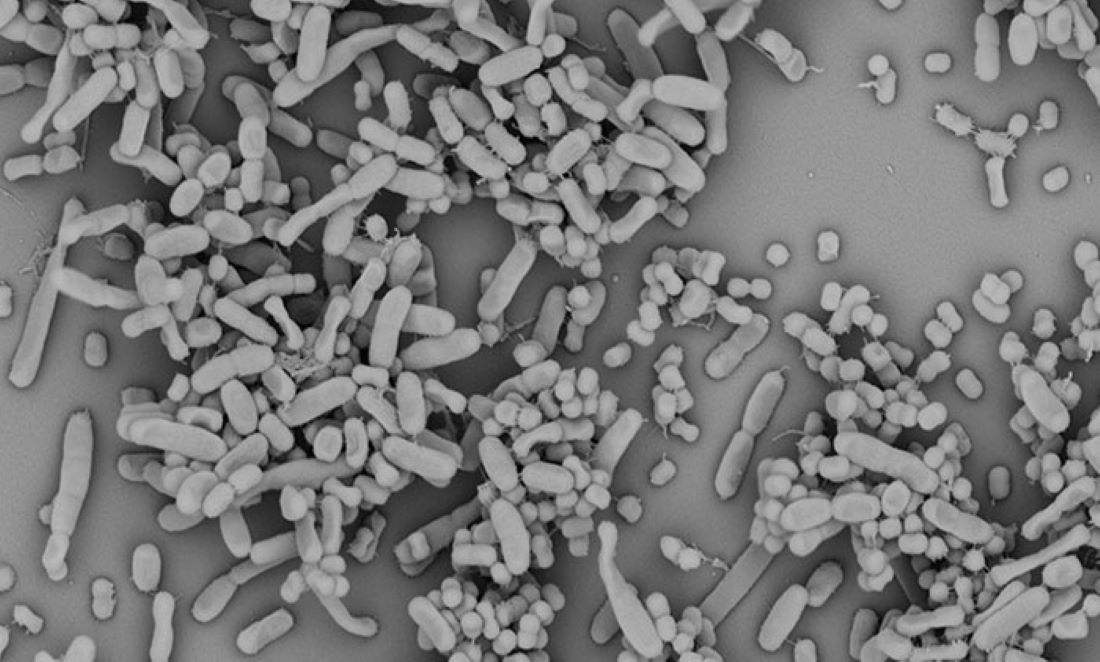

Scanning EM of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii growing in a biofilm | Dr Lucie Semenec, Macquarie University

What’s truly terrifying is that these pathogens can live in hospitals on walls and other hospital surfaces for up to 4 months. Recent research also tells us Acinetobacter baumannii can live without water for 1 year and then become infectious again if given the right environment.

The discovery

Australian hospitals do not provide data for infection rates of these two bacteria growing together, so Amy and fellow co-author Dr Lucie Semenec turned to European data.

The data from Europe showed that, in almost half of all infections caused by one of these pathogens, the other one was present.

Armed with this information, the team from Macquarie University began experimenting with caterpillars of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella.

Galleria mellonella – moth or bark? | dhobern via Wikimedia Commons

As the immune system of this caterpillar is somewhat similar to humans, it provided an ethical alternative to using mice. Dr Nicole Bzdyl from the Marshall Centre at UWA has been awarded a research grant to join Amy’s laboratory to learn how to use and develop infection models with the caterpillars to test new drug therapies.

According to Amy, while looking at the caterpillars, the team found the two bacteria could infect the larvae via collaborative effort.

“We looked at their genome and used RNA sequencing to understand which genes are switched on, and we could see they were activated together,” says Amy.

“We also used an electron microscope to see that they were literally interacting with each other.”

The team also put both bacteria in different media in a cross-feeding experiment. The experiment showed that both bacteria feed each other but Klebsiella pneumoniae eats more sugar than Acinetobacter baumannii.

The need to change screening methods

“This research adds another piece of information for policy makers,” says Amy.

“Hospitals need to routinely screen for the presence of multiple species within infections because even low levels of another bacterium can affect outcomes. Then if patients aren’t responding to treatment, clinicians can use an antibiotic that will cover both pathogens,” she adds.

“Combination therapy tends to be used more and more because we’re running out of options.”

According to Amy, the longer someone is inside a hospital, the higher their risk of developing a second infection.

“We need to take our hospital stays more seriously and think twice about unnecessary visits.”