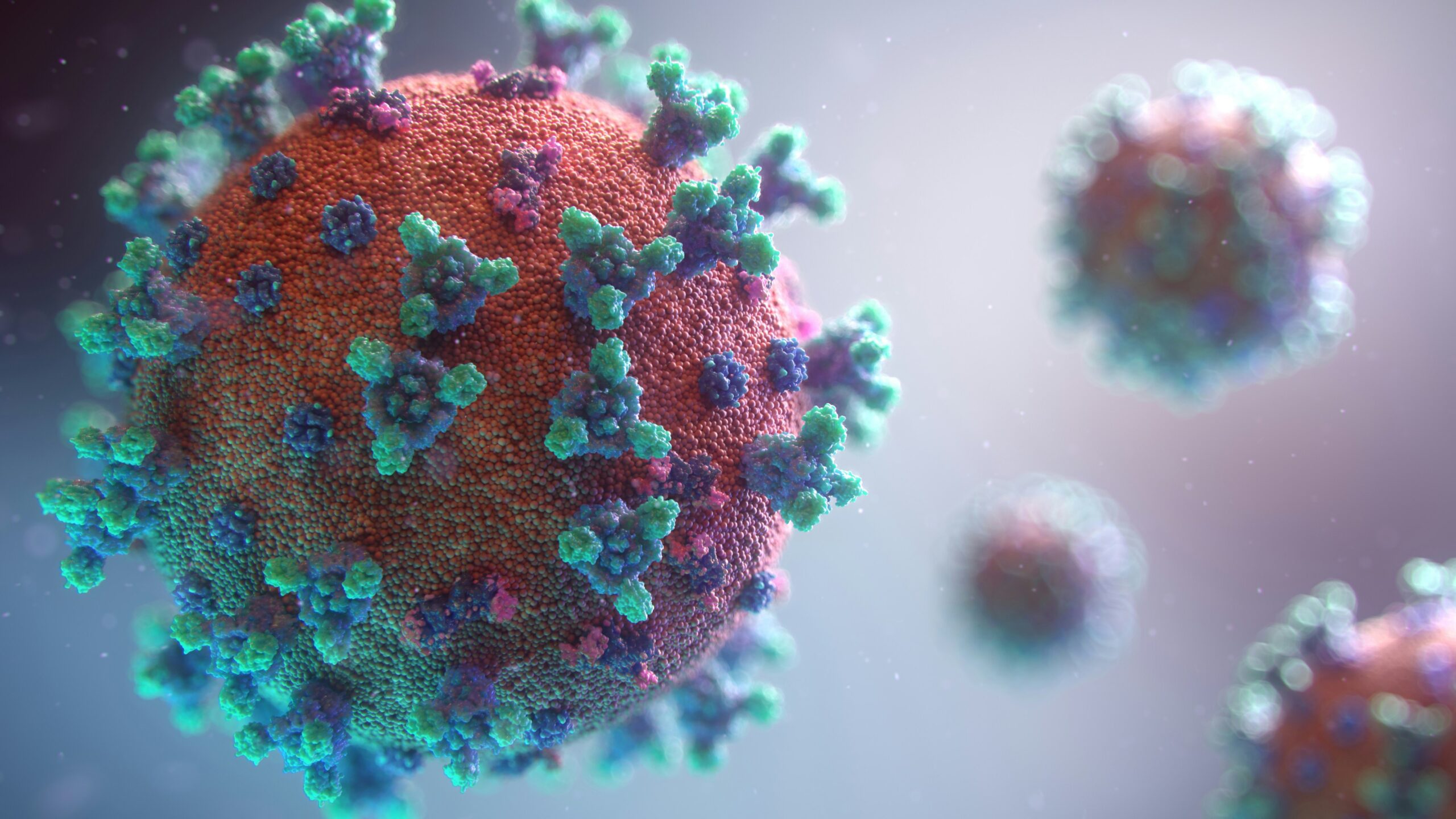

It was a reportedly bat-borne illness that shut the entire world down.

COVID-19 became a household name after the illness spread like wildfire across the globe, infecting and killing millions of people.

But it turns out that diseases cross over from animals to humans fairly often with 75% of new infectious illnesses in humans originating from wildlife.

It’s so common, these types of disease share a common name – zoonoses.

ZOO-WHAT-IS?

A zoonosis is an infectious disease that is transmitted from an animal to a human.

Once a human is infected, the zoonotic disease can mutate and evolve, effectively becoming a new disease that humans don’t have pre-existing immunity against.

The World Health Organization claims there are more than 200 different types of zoonoses, but Australia has only recorded around 50.

Some of these zoonotic diseases include rabies, Lyme disease, Q fever, bird flu and – more recently and most famously – COVID-19.

TREAT ME WITH YOUR BEST SHOT

Zoonotic diseases can be caused by bacteria, viruses, parasites or fungi.

This makes these infectious illnesses complex to treat as the pathogens causing the disease could differ.

For example, antibiotic medication might work for bacterial diseases but not viral illnesses, and some diseases can be prevented with vaccination while others can’t.

They can also be hard to prevent, being transmitted through multiple means, including direct or indirect contact or through food, water or vectors – for example, being bitten by a bug.

HISTORY REPEATING

The first record of humans getting sick from animals is a description of rabies found in the Codex of Eshnunna – a collection of ancient Mesopotamian laws dating back almost 4000 years. The codex decreed that, if a rabid dog bit someone and they died, the owner would be subject to heavy fines.

Jumping forward to the Middle Ages, and new research has found the nerve-attacking disease leprosy could link back to a seemingly innocent animal – the squirrel.

Today, the world is still witnessing diseases transferred from our animal friends, including avian influenza (known as bird flu) and swine flu, which is transferred from pigs to humans.

OLD MACDONALD HAD A …

The most at-risk group of people are those working with animals – think farmers, veterinarians, abattoir workers and livestock handlers. That’s not to say others can’t be struck down with the disease.

Anyone in contact with domestic, agricultural or wild animals could be at risk of getting sick, even if the animals themselves don’t appear sick.

Worse still, once a zoonotic disease transfers to humans, there is a high risk of human-to-human transmission kickstarting the next zoonotic pandemic.

When an epidemic of this scale occurs, the impact goes further than just human health, with economic repercussions from global diseases also leaving a mark.

For example, the Australian economy suffered a loss of $158 billion as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic – an impact that governments are still trying to recover from today.

PREVENTION IS PARAMOUNT

As urbanisation increases and reduction in natural habitats continues, so too does the risk of disease.

This is due to an increased chance of contact between humans and animals, which allows zoonotic diseases to merge and spread.

But there are some simple actions people can take to reduce the risk, including getting vaccinated, disinfecting or washing hands and, if necessary, wearing personal protective equipment.

While these preventive techniques were taught during the COVID-19 pandemic, they could remain the best defence against other zoonotic diseases.