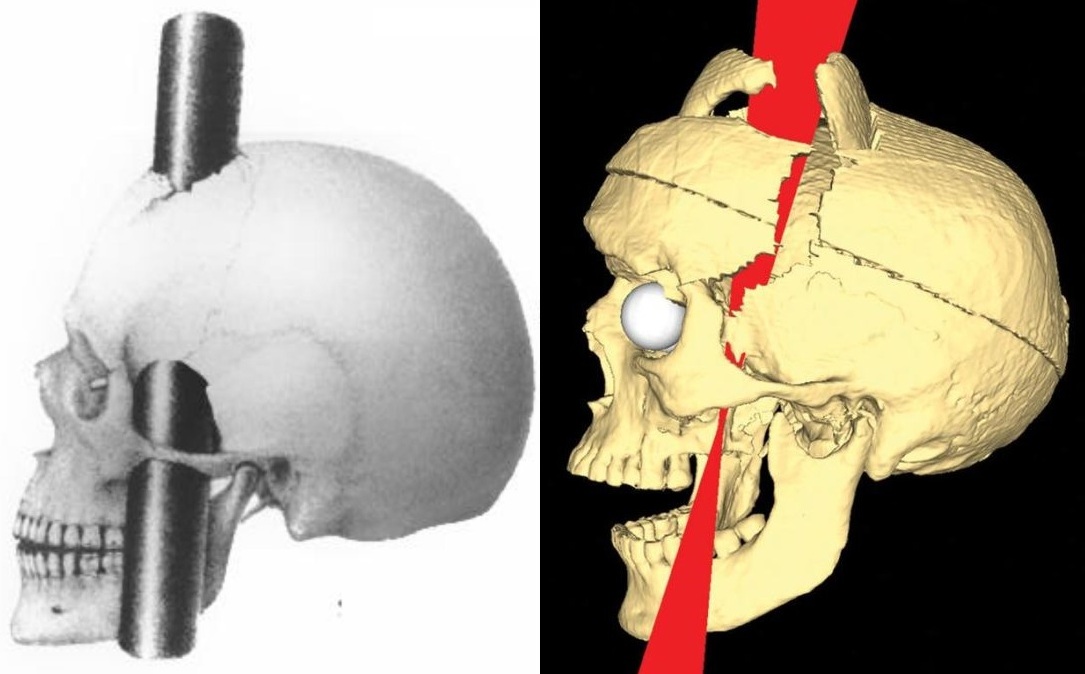

About 200 years ago, a railway foreman named Phineas Gage had a very bad day. While clearing up large rocks with the aid of explosives, misfortune struck and a 6kg metal rod, known as a tamping iron, shot up at Phineas and went straight through his head.

Miraculously, Phineas survived the event. However, it’s alleged that his personality changed drastically. To make his story even more incredible, this sudden change in personality only lasted a few years. It is said that, by the end of his life, Phineas had somewhat recovered his original personality.

The rod pierced his brain and changed him, but the brain had rewired itself over time to repair the damage.

His doctor found it very weird.

Thought of the day

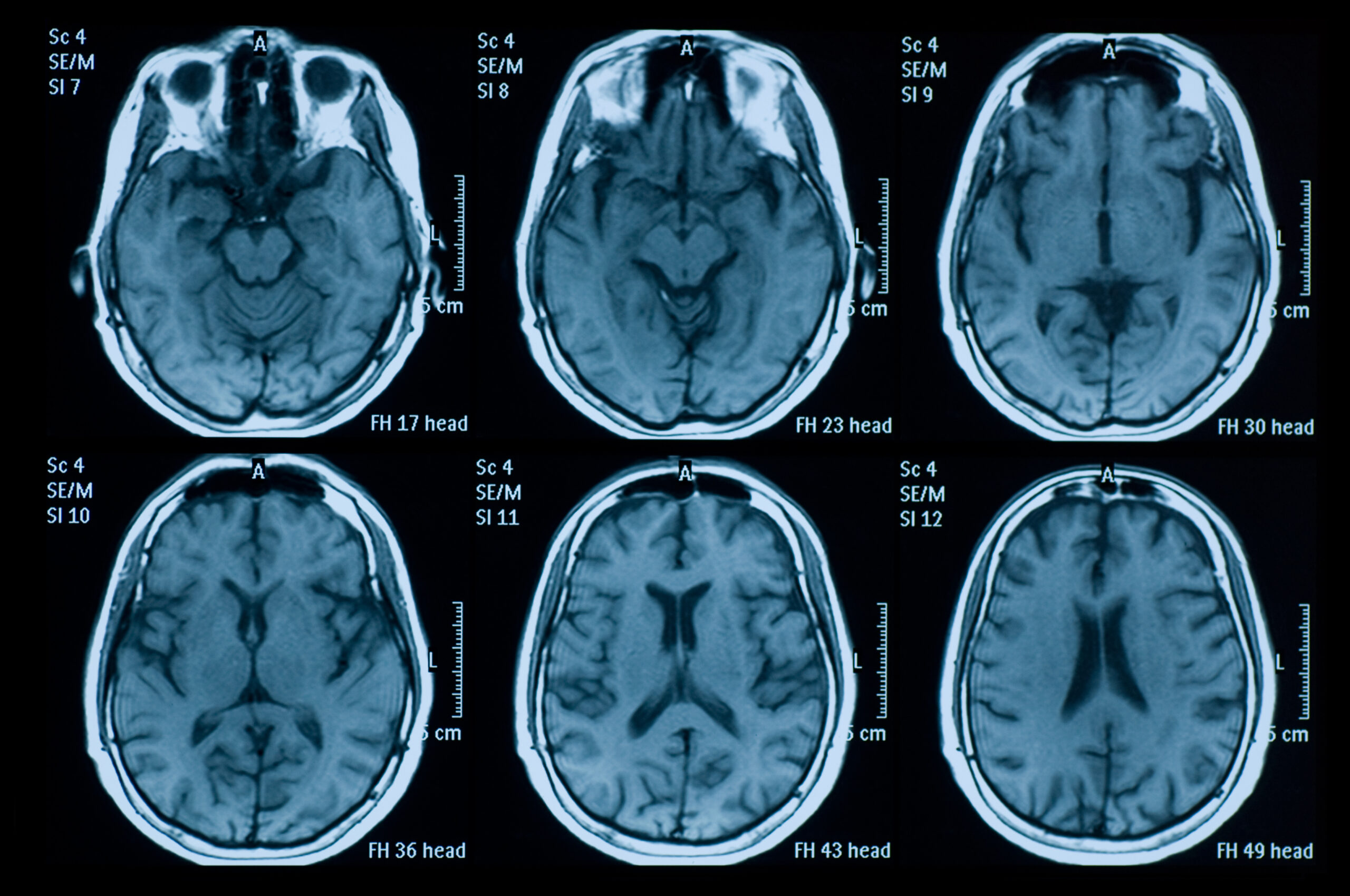

Neuroplasticity describes the brain’s ability to adapt to changing circumstances and heal itself. It’s the basis of a variety of medical interventions.

For example, if a stroke patient loses the function of one limb, they often undergo constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT). The rehab program involves constraining an unaffected limb by putting it in a sling or strapping it close to the body. This way, the patient can concentrate on forcing their stroke-affected limb to start moving properly.

The success of CIMT and other similar therapies fuels scientists to do further research on how best to harness the power of neuroplasticity.

Stimulating new pathways

One novel way of harnessing neuroplasticity is the method of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

The name is a very complicated way of describing the application of magnetic fields to the brain via charged copper coils.

Doctors currently use it for treatment-resistant depression, but it has potential to be used for other neurological conditions.

GIPHy

“Brain stimulation improves connections throughout the brain, and so we can use it to try and restore healthy brain function,” says Professor Kate Hoy from the Cognitive Therapeutics Research Program.

She studies how to use rTMS for Alzheimer’s disease.

As Alzheimer’s disease develops, toxic proteins build up in the brain. When typical neural pathways become blocked, the brain cells start misfiring.

Once affected, the neural pathways stay damaged even if treatments remove the toxic proteins. The Cognitive Therapeutics Research Program think rTMS pulses will encourage neurons to repair their connections.

Researchers in Western Australia are also investigating rTMS. Dr Alex Tang and the Brain Plasticity Lab are interested in how rTMS could affect the ageing brain.

Pinky and the Brain, Brain, Brain, Brain

“The basic setup is a device linked to a stimulation coil, which is just a bunch of copper wires wrapped in a certain shape,” says Alex.

“The machine will charge up a very large amount of current – thousands of amps in about 300 microseconds. Then it runs through the coil to generate a very quick magnetic field.”

Basic rTMS and patient setup | Baburov via Wikimedia Commons

Alex’s research found rTMS improved the neuroplasticity of ageing mice. It didn’t make a new Pinky and the Brain, but it did show there was potential for using rTMS to treat diseases that occur as brains age.

The lab found rTMS signals reduced the expression of genes related to brain inflammation. Less inflammation means less damage to brain cells.

However, the team are yet to find the exact reasoning for how magnetic fields are changing the brain.

“The bottom line is we don't know for sure. We do have evidence to suggest that rTMS is changing the synapses in the brain,” says Alex.

Neurons are the nerve cells inside our brain that are responsible for sending information throughout our body. Individual neurons are connected by synapses that allow electrical impulses to travel between neurons.

“Depending on the stimulation, you can change the strength of neuron connections. That’s the main way people believe the simulation is affecting the brain,” says Alex.

Watch this space

The rTMS procedure is safe except in some cases of brain trauma or epilepsy. However, in the future, rTMS might treat these conditions as well. In 2021, an epileptic man underwent rTMS to stop him suffering up to 200 seizures a day.

The side effects of rTMS include headaches, dizziness and, very rarely, seizures. But since its adoption in the late 80s, patients don’t seem to have experienced any long-term side effects yet.

“We look at the short and long-term changes that rTMS has on the brain. We are trying to identify all the good changes that are happening and if there are any unwanted side effects,” says Alex.

According to Kate, researchers have a good understanding about the safety of rTMS.

“There's nothing in the last 30 years that would lead us to think that there will be any significant long-term effects. But certainly, we still must look at that.”

The science of neuroplasticity has certainly changed a lot since Phineas Gage’s unfortunate but fascinating accident. However, the brain is still a huge mystery.