“It was terrific,” is how University of New South Wales Associate Professor Kristopher Kilian describes the moment his research team realised what they were seeing.

“This is why science is so fun. When you make a discovery like this – there's nothing like it.”

Kris’s research group had done something no one had done before.

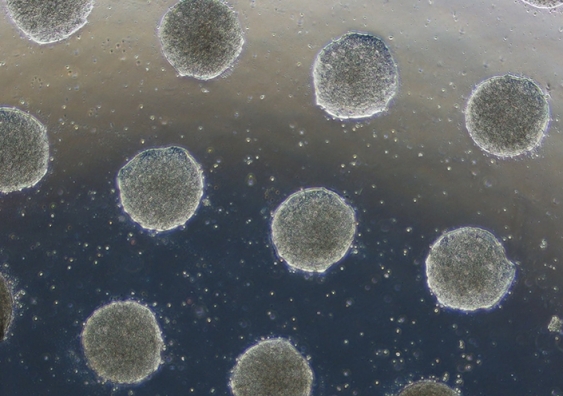

They’d prompted human stem cells to undergo a process called gastrulation.

It’s a pivotal stage of embryo development when stem cells start to transform into different tissues, ultimately leading to all the different parts in a human body.

And – for the first time – they’d done it simply by placing the cells in a special material.

Associate Professor Kristopher Kilian with his research team | Yi Pei

A GOOD DAY IN THE LAB

Like many great scientific breakthroughs, it was unintentional.

The team had planned to trigger gastrulation by adding chemicals that start differentiation – something researchers do all over the world.

“It doesn’t mimic what happens in a living embryo, because it’s sort of like taking a large sledgehammer to put in a carpet tack,” says Kris.

“It’s a little over the top, and you lose some of the nuance … that might happen in a human embryo that’s developing in a pregnant mother.”

how did they do it?

The researchers first placed the stem cells in a new biomaterial they were studying.

But when PhD student Pallavi Srivastava checked on the cells 2 days later, gastrulation had already started.

The team repeated the experiment, with the same results.

“In every lab in the world, they just remain [as stem cells], but when we put them on our materials, they started differentiating,” says Kris.

“I was stunned.”

It appears gastrulation was triggered by the combination of a soft material (similar to the human uterus) and confining the cells to restrict their movement.

“It was the first report of how the physical aspects of this microenvironment – confinement and stiffness – could make gastrulation just happen,” he says.

“That’s pretty exciting.”

‘BODY-ON-A-CHIP’

In 2012, two scientists won a Nobel Prize for the discovery that mature, specialised cells such as skin cells can be ‘reprogrammed’ to become immature stem cells.

Kris says being able to trigger gastrulation in these stem cells quickly and inexpensively could be “game changing” for medicine.

“For instance, in cancer research, if you could take a chunk of somebody’s tumour after a biopsy and then also take their skin or blood cells, reprogram them and form little mini livers or little mini hearts, then you could have a ‘body-on-a-chip’,” says Kris.

“You could develop drugs that kills the cancer but are also not toxic to the liver, not toxic to the heart.”

EXPECT THE UNEXPECTED

Kris stresses that, while we can initiate gastrulation, the cells need more signals to continue.

The technology certainly can’t be used for cloning or to create a new person.

But Kris is interested in whether other materials or chemicals can trigger cells to start forming more-complex tissues.

In the meantime, he’ll keep telling his students to “expect the unexpected”.

“We can be as clever as we want, and we can come up with all these hypotheses and ideas, but oftentimes it’s the surprises that really make huge impacts,” says Kris.