The story of Wave Rock begins millions of years ago, as rock met water – but probably not in the way you’d expect.

“Wave Rock is an upstanding part of a huge ancient crustal mass called the Yilgarn Craton,” says David Newsome, Professor of Geotourism at Murdoch University.

You’ve probably seen the Yilgarn Craton before and haven’t realised it. It’s the enormous chunk of the planet’s crust that makes up most of southwestern Australia.

That rock has been around for a long, long time. Although it’s stable, it’s not indestructible – and that’s the key to Wave Rock’s mysterious shape.

“It’s just the vast expanse of time, where there’s been no subsequent mountain building, no volcanism, no earthquakes, no uplift. The land that once covered Wave Rock was just gradually worn away,” says David.

“At the end of the day, this particularly hard piece of rock then ends up as an upstanding piece in the landscape.”

Beneath the fields of eroded bits and pieces, the remaining rock was weathered into domes beneath the ground. Erosion, over a vast expanse of time, exposed the granite domes to the surface, and the structure we now call Wave Rock began to form.

Straight off the top of my dome

Because of its shape, it’s easy to assume that wave rock formed because of flowing water or blowing wind – but that doesn’t seem to be the case.

For starters, there’s not enough wind or flowing water in the area to cause that much erosion, even over millions of years.

But the biggest clue is that, according to geologists, the landform’s wave shape continues below the current ground level, for at least a metre, without flattening out. There’s only one conclusion that makes sense:

“It was born underground,” says David. “The granite formed deep under the ground and was then revealed. Post formation, the landscape has been eroded back, exposing the magnificent rock itself.”

So how does a spectacular shape like that form?

Eroding me softly

It turns out water doesn’t have to be moving to eat away solid granite. Just sitting around and dissolving the minerals that hold it together, over millions of years, is enough.

“At that particular site, there was a fracture under the ground that weakened the rock,” says David. “That rock is covered in soil and unconsolidated material called regolith.”

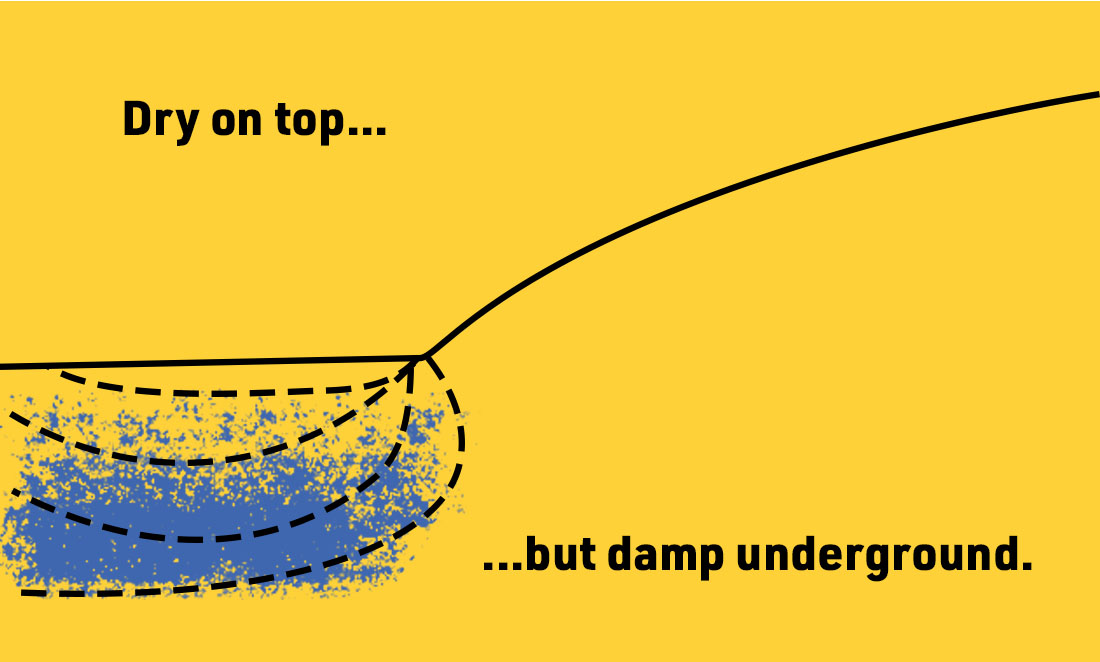

That soil hangs on to water, just like the soil around a pot plant.

“Under the ground, there was all this weathering going on, because the water was slowly but surely breaking down the rocks. The fracture was a weak zone, so it sort of worked faster there than it did anywhere else,” says David.

And just like your houseplant, it dries out at the top first. The bottom layer stays wetter for longer.

“So it starts to eat into the side of the main dome over time,” says David.

With this theory, over millennia, the bottom dissolves more than the top. Peel the sandy covering away, and you’re left with … well, this:

New wave

According to David, appreciating geology is like appreciating wine or fine art.

“Wave Rock has something to offer all of us because it has these secrets that just need to be brought out.”

Standing at the base, it is undeniably cool to know that Wave Rock emerged fully formed from the Earth, like some kind of Greek God on an epic journey.

“When you know the granite that makes up Wave Rock is 2.7 billion years old – that is a pretty profound concept,” agrees David.

This knowledge can also help us understand some of the stuff we can’t see, happening beneath our feet.

A quick walk around the rock reveals that there’s still a lot of sand out there – and there’s plenty more rock left in this patch of the Yilgarn Craton. That means it’s possible – likely even – that, as you visit, more Wave Rocks are forming right under your feet.

Just like the first one, these new waves will take millions of years to form, so we should appreciate the one we’ve got.

“It’s important that it’s not defaced, doesn’t have stuff hammered into it or people riding bikes over it and climbing on it and stuff like that.

“Wave Rock … its key asset is its wildness, what it represents as a natural feature,” says David. “Deep within us, there’s something there that gives us recognition that we evolved in nature.”

“And I’m of the opinion that, in the future, we’re going to be yearning for that wildness more than ever.”