If you were going to charm a fish with a mixtape, what would you play?

University of Exeter marine biologist Tim Gordon has the answer.

Tim recorded healthy Australian coral reefs and played them in dying reefs to lure fish species back.

“For now, it’s just a proof of concept. We’ve shown we can do it. One day, we may be able to target specific fish species by mimicking their calls,” says Tim.

In their experiment, Tim’s team found fish could hear the speakers up to 100 metres.

Many fish returned to the dying reefs, but the most remarkable return was the damselfish.

After 40 days, the number of damselfish doubled in reefs with speakers compared to reefs without.

NEWT PLAY THE FLUTE, CARP PLAY THE HARP

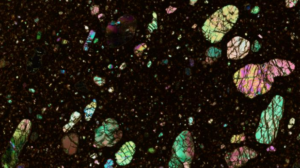

You may not think it, but coral reefs are noisy places.

The rushing sound of fish torpedoing through water, hunting calls, mating calls and clicking claws of shrimp.

These sounds are signs of a healthy reef, full of many different life forms.

Wandering fish that hear a reef are attracted to it, searching for a tasty snack or a new home.

“Fish actually have an excellent ability to hear,” says Tim.

“They don’t have ears like us but these stones called otoliths covered in hairs.”

“Some use their swim bladders as amplifiers,” says Tim.

Unsurprisingly, dead reefs are much quieter than living ones. But by tricking fish into settling a dead reef, the reef can be brought back to life.

VALE VERRUCOSA

Reefs can die a number of ways, but the most pressing is coral bleaching.

When temperatures climb, carbon dioxide from the air mixes with hydrogen in the ocean to form carbonic acid.

This can stress out coral, causing them to shed the helpful photosynthetic bacteria that cling to them.

With bacteria gone, coral often sickens, starves and dies.

Coral is the foundation of a reef. When it goes, the entire reef begins to starve. Fish will abandon the reef for a new home.

SO LONG AND THANKS FOR ALL THE FISH

Experiments on Australia’s Lizard Island show that listening is one way that fish search for a new home.

As larvae, they are also sent to settle nice-sounding reefs to make sure their local reef doesn’t become overpopulated.

Normally, 60% of those larvae die on the first day of settling a new reef. But with human aid, dying reefs may actually be better places for larvae to settle as there are fewer predators.

And since fish larvae are close to the bottom of the reef food chain, by bringing them back, the reef can begin to bounce back too.

As long as the planet continues to warm, reefs will be vulnerable to mass bleaching and other disasters.

By reviving reefs, we can give coral time to adapt to more acidic oceans. We can also recover reefs after natural disasters and move endangered fish species to managed reefs to protect them from going extinct.

Sounds pretty good to us.