Restoring natural ecosystems to their pre-disturbance state is complicated. Whether the disturbance is mining, pollution or a natural disaster, environmental restoration projects are no mean feat.

Over millions of years, Australian wildlife have adapted unique responses to their local environment. A good example is the response of Australian flora to fire events.

A team of researchers from Murdoch University and Kings Park Science recently published a study that looked at how banksia woodlands that are restored after mining respond to bushfires. Their findings show that there’s a lot we need to understand – under the surface.

Where there’s smoke, there’s flora

Bushfires are often what stimulate seeds to germinate or plants to resprout. They’re essential for the regrowth and rejuvenation of many of WA’s native ecosystems. Ebony Cowan and her team wanted to know how bushfires affect newly restored environments.

Newly germinated seedling | Ebony Cowan

“When we’re thinking about restored environments such as those after mining, they’re often quite different to natural ecosystems,” says Ebony.

Due to effects of previous land use and restoration processes, restored environments can have different species composition and soil structure.

“We’re not too sure how something like a fire may change that system.”

Seedbanks in native ecosystems usually build up over decades, ready to spring out of the ground once a fire has passed. But Ebony’s study looks at how the seedbanks in restored woodlands develop and respond to fire over time.

Smoking out the truth

As it turns out, starting a fire in the Australian bush is a bit of a no-no, so Ebony’s team had to get a little creative for their research.

“We did a smoke tent trial. It was basically just applying smoke onto different areas in the mining restoration that were at different ages,” says Ebony.

Smoke tent being used | Ebony Cowan

“The idea was to replicate what would happen in a fire. So smoke would linger, and that would break the dormancy cue that a lot of species require for their seeds to germinate.”

The result? Newer restoration areas tended to have a lot more annuals germinating (species that live for 1 year). But the older woodlands were more likely to have perennials germinating (longer-lived species like bushes and trees).

The need for seeds

That difference in germination response between species can have a big impact on overall ecosystem health.

“We value [plants] for general services like water filtration, carbon storage and habitat. The perennial species make up the bulk of that kind of work,” says Ebony.

After a fire has passed through, perennial species help ensure that an ecosystem is renewed. Without them, restored areas can slowly deteriorate.

“When we restore a site, we don't want to be coming back every 5 or 10 years to try and get it back to a good state,” says Ebony.

“We need to think about the future maintenance of these sites and how they’ll persist into the long term.”

Understanding responses to disturbances such as fire is key to this.

Sowing seeds for the future

During ecosystem restoration, some practices can do a lot for seedling health – for example, using high-quality soil from healthy ecosystems to aid in the restoration of a cleared area.

“Having topsoil that is freshly collected is quite important because it will contain a lot of species,” says Ebony.

“But when we are establishing these sites, it’s not as simple as just putting down some soil with seeds and letting it go. Other practices such as [soil] ripping reduce compaction and aerate the soil.”

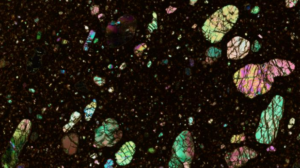

A healthy seedling response | Ebony Cowan

In addition to the restoration practices we currently implement, long-term monitoring of the seedbank can help us be ready for future problems.

“Some species also can have quite long seed longevity … their seeds can persist for like 40 years. So an acacia, for example, might have died out 20–30 years ago, but its seeds could still be there.”

“I think [monitoring] can help us to see when shifts [in ecosystem health] may be about to occur. Instead of things changing and then you’re like ‘oh goodness, time to do something!’,” says Ebony.

Life below ground can be challenging to understand and measure. But by keeping track of how our ecosystems are preparing for the future, we can become prepared as well. And eventually, this will make it easier for us to fulfil our responsibility to this land and the unique natural beauty it holds.

Interested in learning more about fire and its impact on the people and environment of Western Australia? Tune into the second season of the Elements podcast.

Across five episodes, we cover everything from festival bonfires to devastating wildfires, from echoes of ancient knowledge to the technological possibilities of the future. It’s going to be lit🔥

All episodes out now on all your favourite podcast platforms.