When it was young, our state was hot. Volcanically hot.

So what happened?

It starts with a breakup

1.3 billion years ago – around the time the first fungi were evolving – the rock that would become northern Australia was pressed up against the rock that would become northern China.

Part of the supercontinent Nuna, they floated on the Earth’s mantle – a 2900km-deep ocean of magma.

Driven by a burst of heat from the planet’s core, a hot plume formed beneath the splitting continents.

An updraft of magma pushed against the thin, cracked crust, forcing its way up and out.

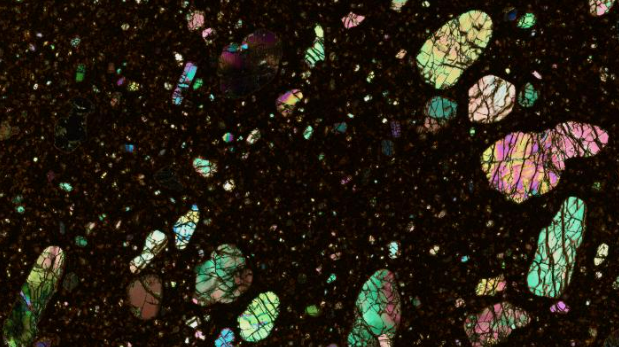

Caption: Carried on tides of magma, Australia and China drifted apart

Credit: Olierook et al, 2023 (CC BY 4.0)

Some magma reached the air and flowed freely as lava across the surface.

Some hit groundwater and exploded, forming craters and geysers.

And some cooled and hardened, threading the crust with veins of volcanic rock.

Imagine modern-day Iceland, covered with fungi instead of frost, and you’ll have a pretty good idea of what the Kimberley used to look like.

When the magma couldn’t push up any more, it pushed outwards, dragging our two young continents along with it. The supercontinent broke up, and the hotspot cooled.

With nothing to light it up or push it around, the rocks of the Kimberley were still – ready to be shaped by a different kind of flow.

A different kind of hotspot

Despite its dramatic origin, wind and water have shaped most of WA’s natural treasures.

Erosion carved astonishing landscapes from Katter Kich (Wave Rock) to Purnululu (the Bungle Bungles).

It’s given us biological treasures too. Those ancient rocks broke down into soils with almost no nutrients, and to thrive here, native plants developed an incredible variety of adaptations.

We may no longer be a geological hotspot, but we are a biodiversity hotspot.

It’s also given us a far more literal kind of treasure.

As magma forced its way to the surface, it collected rare, colourful diamonds formed deep in the Earth’s crust and brought them to within a few kilometres of the surface.

It was erosion that finished the job and brought the surface closer to them.

In 1985, those diamonds were found. Our ancient volcano became a different kind of crater – the Argyle Diamond Mine.

Credit: W. Bulach via Wikimedia Commons(CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Argyle Diamond Mine closed in 2020. It produced 150,000kg of diamonds over 35 years, making it one of the largest diamond sources in the world and the only known source of pink and red diamonds.

Not bad for a volcano you didn’t know existed.