Using underwater microphones, that’s exactly what one team of researchers did.

Now, they’re taking their first steps towards tracking dolphins the same way other dolphins do.

Whistle while you work

We humans don’t usually walk around calling our names out so people can find us – but Bottlenose dolphins, it turns out, sort of do.

Professor Christine Erbe from Curtin University’s Centre for Marine Science & Technology says each Bottlenose dolphin has a unique ‘signature whistle’ that identifies the animal.

“It’s almost like these animals having names,” she says.

“It’s a ‘here I am, here I am’ to signal where they are and for others to respond,” says Christine.

It’s as if every dolphin came with their own built in tracking signal. If you’re trying to find a better way to track dolphins, signature whistles are a great place to look – or rather, listen.

Found sounds

With support from Fremantle Ports and Australian Acoustical Society, and the Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions, scientists placed underwater microphones (called acoustic loggers) along the Swan River and in Fremantle’s Inner Harbour.

“They record day and night for months and you get a wealth of data back,” says Associate Professor Chandra Salgado Kent from Edith Cowan University.

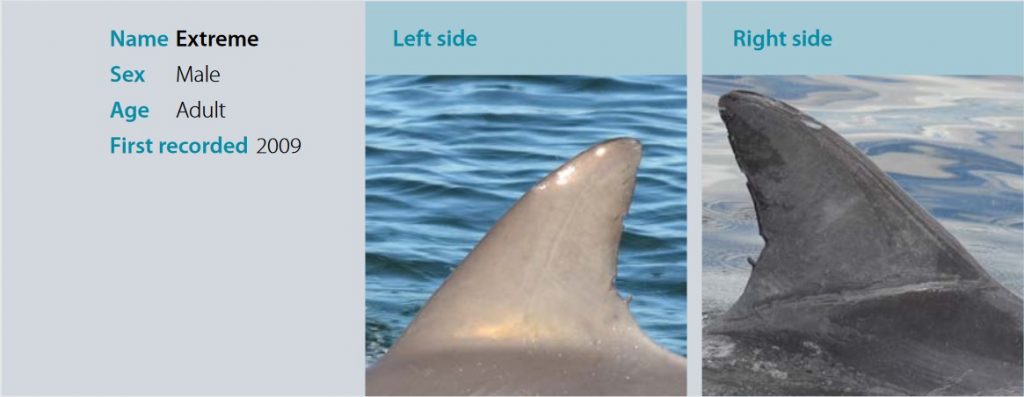

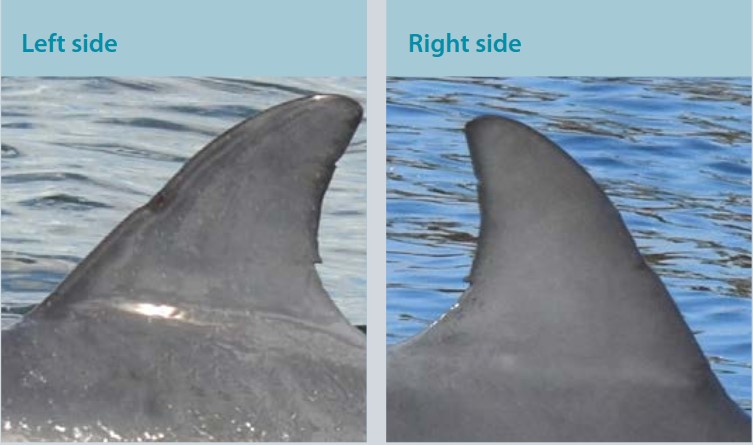

Meanwhile, a team of researchers and citizen scientists are keeping tabs on the dolphins with the help of the Swan River Fin Book.

The next step is to match recorded whistles to the date and time of confirmed dolphin sightings.

Harder than it sounds

That might sound straightforward, but there’s a bit of a catch.

“Dolphins are social animals”, Chandra says.

“They live in groups, where many have long-term relationships and spend a lot of time together.”

Dolphins spend so much time together, in fact, that in this data they didn’t manage to record any dolphins on their own.

That makes it a little trickier to say exactly who they were listening in on.

“What we came up with was a list of probabilities that certain individuals produce certain whistles,” says Christine.

But they need more data to say for sure.

“We think that if we recorded for a long enough period, we would hear enough different combinations of animals that we can tease apart whose whistle belongs to whom,” says Christine.

“We just don’t quite have enough data to do that yet.”

Staying heard above the noise

The team hopes that sound can help complete the data from sightings. Recordings, Christine said, can reveal what dolphins are doing at night, and in places that observers can’t see or access.

It will also help the researchers understand how human-made noise in the river could impact the dolphins, says Chandra.

“In the underwater world good visibility is not always a given, so they can’t depend on their sight,” she says.

“Understanding how they’re producing sound, what it’s for, how they’re using it, really allows us to better understand their capacity to adapt to a changing environment.”