Western Australia has embraced the charismatic quokka as our tourism mascot.

But here at Particle, we think the quokka is missing a sidekick. Given that the quokka has the adorable factor covered, we’d like to suggest a sidekick with a bit of mystery.

Introducing the Blind Cave Eel.

While this guy may not be a looker, it is a bit of an enigma and the world’s longest cavefish.

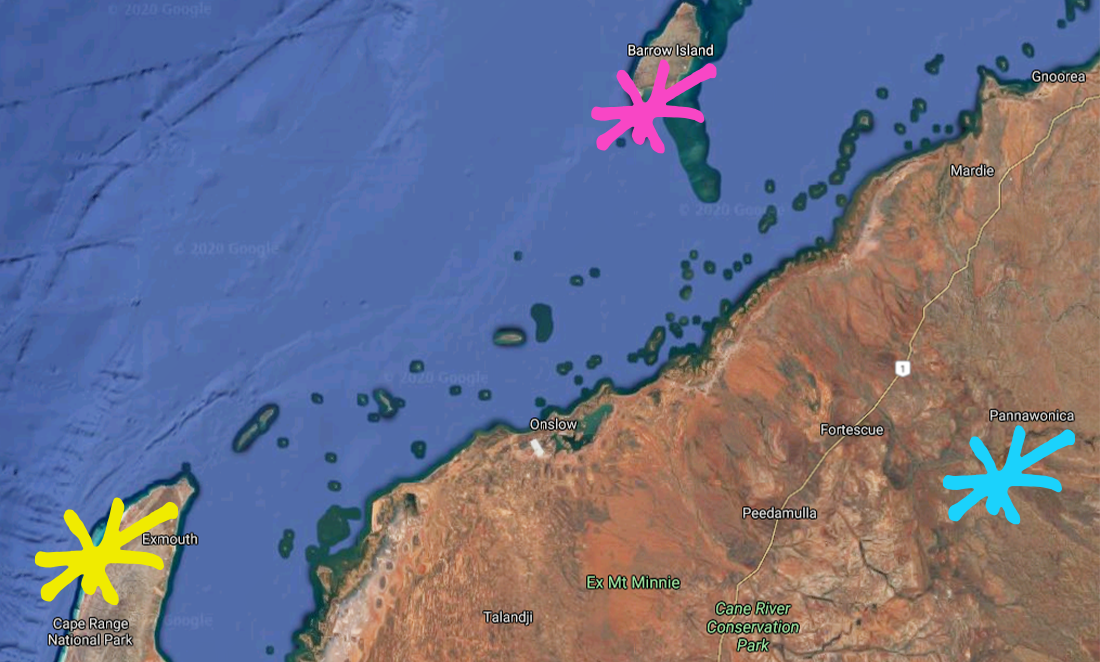

It lives in underground caves across the Pilbara—Barrow Island off the coast of Dampier, Cape Range near Exmouth and Bungaroo near Pannawonica.

Strangely, these cave systems are separated by hundreds of kilometres.

So how did the Blind Cave Eel end up in completely isolated environments? (We’d like to say it hitched a ride in the pouch of a helpful quokka, but this just isn’t true.)

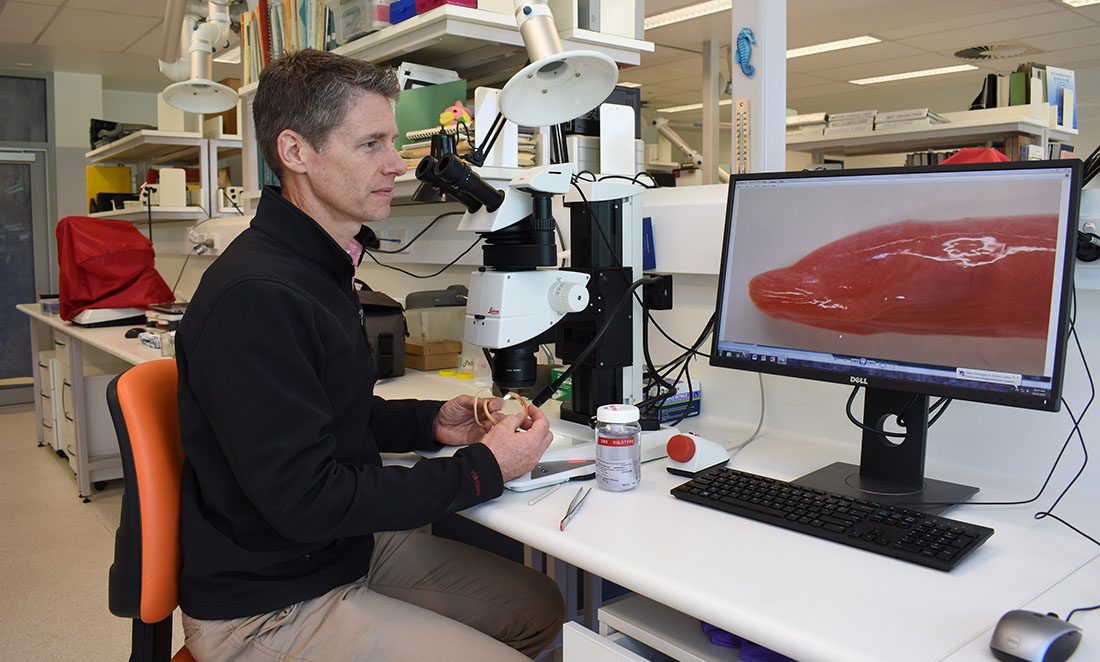

Dr Glenn Moore, Curator of Fishes at the Western Australian Museum, says for 60 years the blind cave eel was only known to exist in one location.

“But we now know they’re in other locations, separated by distances we thought they were incapable of crossing,” Glenn says.

So how did the eel cross the … desert?

Blind Cave Eels live in underground freshwater pockets surrounded by inhospitable saltwater. They’re effectively marooned on a desert island.

But how did they get on those islands in the first place?

The reason the Blind Cave Eel populations are genetically similar yet physically independent is down to geography and geology, Glenn says.

Imagine 50 people are picnicking in a park. Suddenly, it starts raining and they scramble to shelter under the trees.

While it was sunny, people were walking around. But in the rain, separate groups are stuck under trees.

That’s what happened with the Blind Cave Eels. A change in their environment restricted their habitat.

But instead of a downpour restricting the Blind Cave Eels, it was probably rising sea levels, Glenn says.

“We think that, in times of lower sea levels, the subterranean Blind Cave Eel was able to travel more widely,” he says.

“But in higher sea levels, they’re restricted to their freshwater pockets.”

Branching out

Remember the groups of people sheltering in the park? If they have been sheltering for a long time, you might expect the groups to act a little differently to each other.

That’s what happened to the Blind Cave Eels. They’re still the same species, but the populations have genetic differences.

“All populations have genetic differences, but the one located at Bungaroo is the most different,” Glenn says.

The Bungaroo population has been independent for the longest, so it’s had the longest time to change.

“While we don’t consider them separate species, we could say they’re all on independent evolutionary pathways,” Glenn says.

“If these populations are kept independent of each other, we’d expect them to become new species, given long enough.”

It’s evolutionary

The Blind Cave Eel is a great example of modern-day evolution, and who knows what their future holds?

In 10 million years, they may have evolved to be cuter than the quokka … although that does seem like a bit of a stretch.