In aquifers up to 100 metres below the ground, islands of subterranean life have existed untouched for millions of years.

Hundreds of sandy hollows and shallow aquifers formed beneath Australia 10 – 30 million years ago.

These ecosystems are separated by hard, calcium-rich stone called calcrete.

Over time and separated from the world, the creatures who live underground have evolved into unique life forms.

Groundwater fauna, called stygofauna, live in these underground systems and include snails, mites, worms and beetles.

The dark side

Among these subterranean islands, insects scratch their way through soft earth and swim through sandy aquifers.

In complete darkness for millions of years, they live in a world of touch.

Blindly, they navigate using texture and vibrations that signal predators and prey.

How species lose physical traits over time has been debated since Darwin first studied blind cave fish.

Do animals only lose traits that waste energy, as in natural selection?

Or are there neutral traits? Ones that don’t hurt or help animals but can be lost or kept through random mutation? This is known an neutral evolution.

Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice

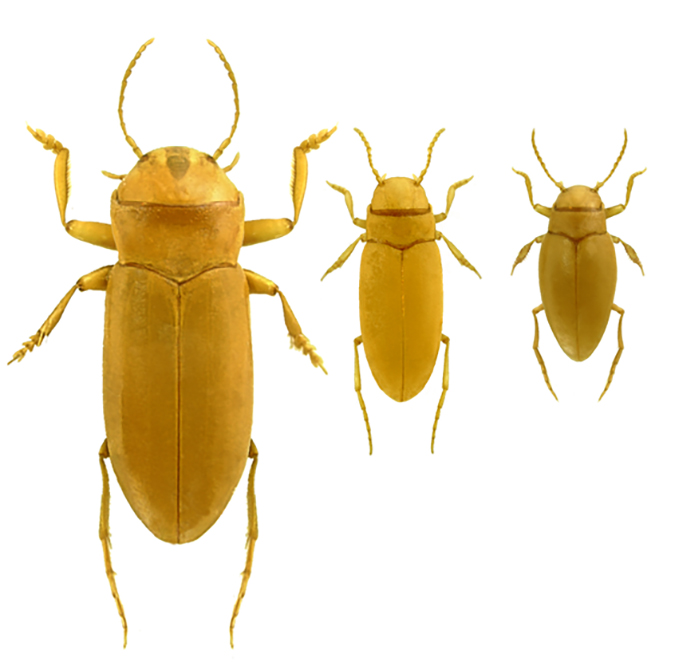

Evolutionary geneticist Barbara Langille studies West Aussie subterranean diving beetles at the University of Adelaide.

By analysing the DNA of beetles living in aquifers, Barbara’s discovering how they lost their eyes.

“We have different enzymes to keep the genes we need functional, so when they’re copied, they don’t have errors,” Barbara says.

Without light, there’s no advantage for a subterranean animal to see.

Errors can creep into the species’ DNA, and because it’s no longer a matter of life and death, those with poorer eyesight can breed.

These imperfections are passed down through generations. Eventually, the species can completely lose its eyesight.

That’s how it’s supposed to work, but not all underground animals go blind.

The light fantastic

Barbara’s research studied six underground diving beetles species.

She placed them in a Petri dish with dark and light sides, then watched which side they preferred.

Five species were completely blind and didn’t favour either side. But Paroster macrosturtensis scuttled to the dark side. It could sense the light despite spending millions of years in darkness.

Barbara says, in one way, this was an odd reaction.

“In another, it helps prove neutral evolution,” she says.

“If it’s a neutral, random process, you would expect maybe some species still have [light sensitivity].”

Evolution: It’s complicated

Barbara’s research suggests evolution may be more complicated than simply selecting good and bad traits.

Ancient DNA can hold mutated, deactivated genes that were once the fins, wings and eyes of their ancestors—and the hunt is far from over.

“We’ve found hundreds of species within these calcrete islands, and there are probably thousands of species we have yet to find,” Barbara says.

“It’s the best system for looking at evolutionary questions.”