The Wheatbelt. 150-odd thousand square kilometres of Australia’s south-west where dark, native vegetation has been replaced with lighter agricultural crops. The difference in colour is something you can see from orbit, but it might also be something you can feel from right here on Earth.

Like an enormous mirror, those crops bounce solar radiation back out to space. That means WA’s Wheatbelt – and the wheat growing there – could become a crucial part of how southwestern WA adapts to climate change.

Simulations show that, just by growing slightly lighter-coloured crops, we could reduce monthly mean daily maximum temperatures by 1.0–1.2°C. To understand how a seemingly tiny change could make such a huge difference, we need to understand albedo – and an emerging field of climate science called geoengineering.

Let’s start with albedo

Albedo is a measure of how colour affects temperature by reflection and absorption of radiation.

“I often use the analogy of wearing a black shirt on a really hot day,” says Dr Jatin Kala, Senior Lecturer in Atmospheric Science at Murdoch University’s Harry Butler Institute.

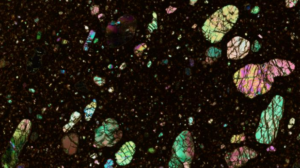

The lighter the colour, the higher the albedo and the more light it reflects. Scientists compare the albedo of different surfaces by giving them a number between 0 and 1.

“Albedo 0, you absorb everything, albedo 1 you reflect everything,” Jatin says.

The same physics makes black cars hotter than white ones. On a larger scale, it can affect the temperature of cities, countries and even our entire planet.

Our polar ice caps reflect a huge amount of radiation. As they melt, they expose the dark soil beneath, which absorbs more heat so ice melts even faster.

(This is called polar amplification. It’s one of the horrifying arrays of unforeseen feedback loops that we’re discovering as climate change intensifies.)

Messing with the system

What Jatin is proposing is the same concept but on purpose – and on a much smaller scale.

“It comes from this idea of geoengineering,” Jatin says. “Basically, some people have thought, ‘Well, we’ve been messing with the climate system, let’s mess some more to cool it down.’”

As far as geoengineering projects go, changing the colour of WA’s entire agricultural region is actually pretty modest.

“People are starting to propose ideas such as putting aerosols in the stratosphere to mimic what happens when there’s a volcanic eruption. Or let’s put mirrors out into space – things which have got a whole bunch of us very nervous,” Jatin says.

But humans have been changing the land we live on for a while already.

“We are changing the properties of the land surface just by the fact that we’ve developed agriculture, we build cities, we live in suburbs.”

“If we pay attention to the colour of things, that is something we can actually manage. If we grow huge areas of crops, let’s just make all of the crops more reflective and see what happens.”

Light simulator

Of course, that doesn’t mean going out and painting the entire Wheatbelt overnight. If climate change has taught us anything, it’s that messing with systems without some serious forethought can have disastrous consequences.

In this case, that forethought is coming from a climate model. It’s a complex calculation incorporating everything from vegetation to soil type – including how reflective they all are.

Each 10 square kilometres of land can be represented by a square on a grid in a climate model. The air above each square is divided the same way. The model calculates how the temperature of the atmosphere changes as you change the land below it.

Then, starting from the actual climate data, Jatin re-ran the past few years of WA’s weather inside a computer – with a twist.

“Basically, I said let’s simulate the past few years of the climate and let’s pretend that all of the crops were more reflective.”

Global models, working with much bigger grid cells, had never showed much change, but zooming in on just WA made a surprising difference. With an increase of just 0.1 to the crops’ albedo, average maximum temperatures over WA dropped by about three times more than the global models predicted.

Solution or stopgap?

Like most geoengineering projects, painting the Wheatbelt is no replacement for reducing the amount of carbon we put into the atmosphere in the first place.

“It does matter, but it’s not going to change global climate,” Jatin says. “What it will change is regional climate.”

It’s a part of the same toolkit as green spaces in cities and reflective rooftops in suburbs. It won’t fix the problem, but it might help keep places liveable for longer.

Colour is also just one part of an already pretty complex calculation for farmers.

“They want crops that are resilient to drought, and they want crops that are high yield, right? And more and more with genomics, people are trying to develop crops which are going to adapt better to lower rainfall and higher temperature and give us decent yield,” Jatin says.

“But something else we should think of is if you have two crops and they overall give you the same yield and they have the same drought tolerance, go for the paler one.”