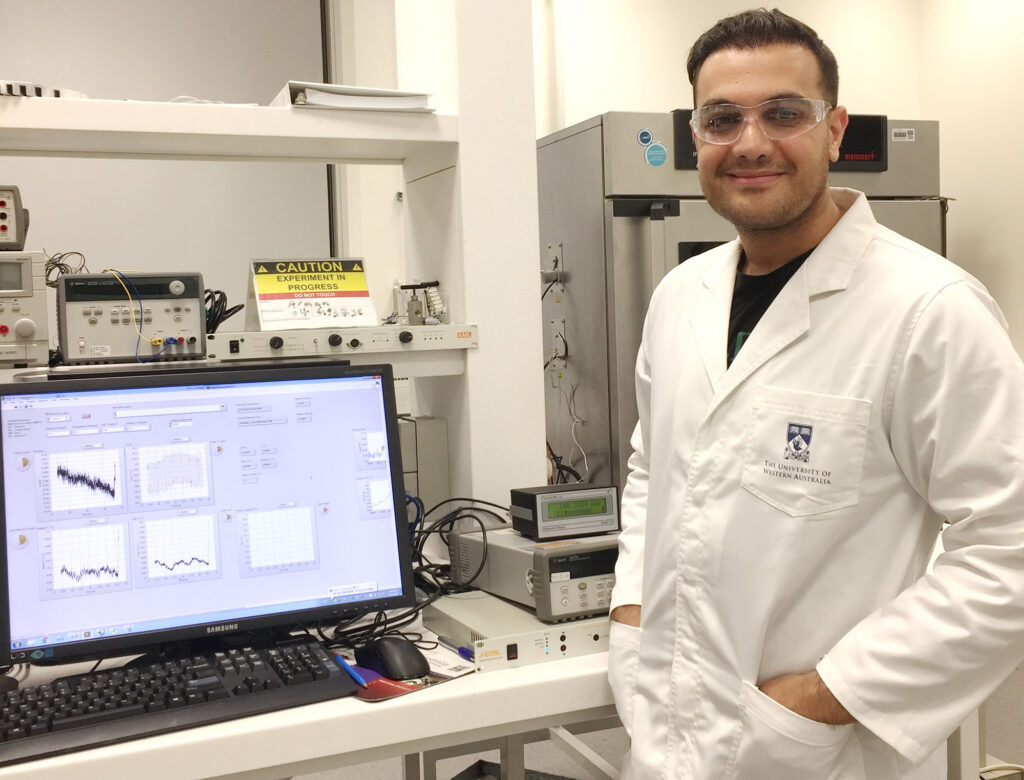

Joint winner of the 2018 Premier’s Science Award for ExxonMobil Student Scientist of the Year, Arman has developed a technique for exactly measuring the freezing point of different mixes of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

He’s also won the 2018 National Measurement Institute Prize, been shortlisted in the WA Innovator of the Year awards, is being wooed by NASA and is keen to use his technology to diagnose heart attacks.

Who cares about frozen gas anyway?

In 2016/17, Australia exported 52 million tonnes of natural gas. Gas takes up loads of space, so it’s liquefied before being transported. This liquefaction happens at temperatures colder than a Perth morning. Think -162°C.

Engineers do their best to remove impurities before liquefaction, but a few stowaway parts per million always remain. And that’s where the problems begin.

Under such super-chilly conditions, impurities can freeze, turning into solids. These solids begin to clog LNG pipelines, just as cholesterol clogs your arteries.

If engineers don’t diagnose the blockage, the pipeline can freeze out, causing the equivalent of a very expensive LNG heart attack.

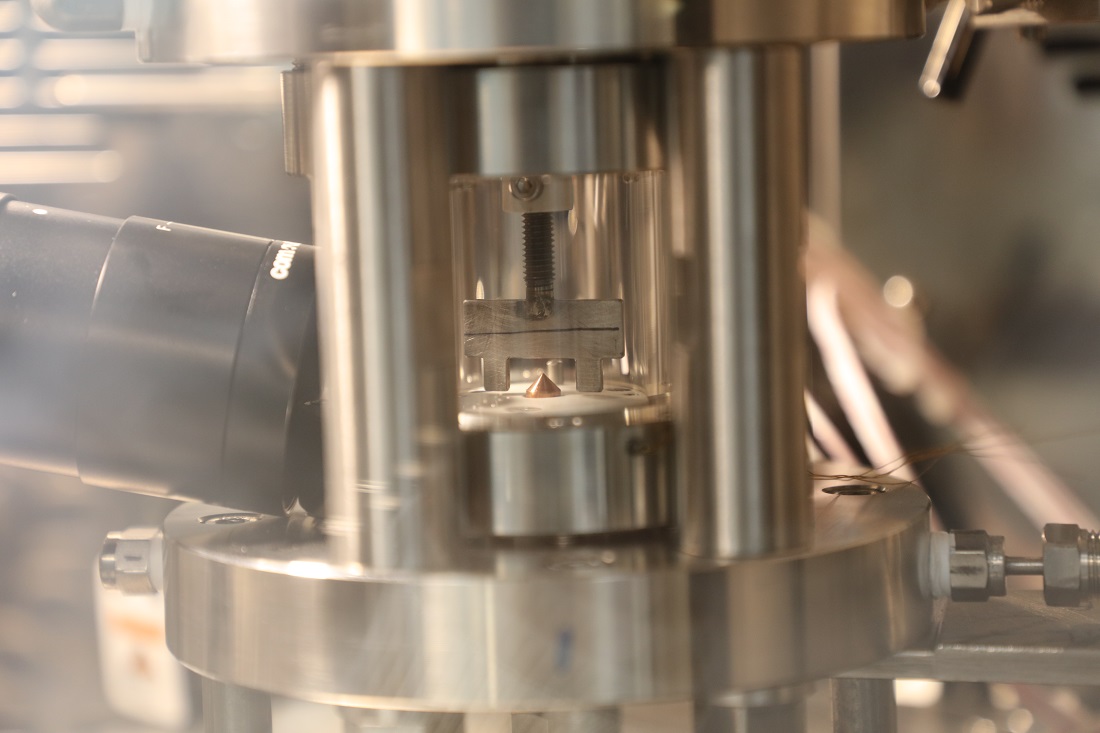

Behold: the CryoSolid Apparatus

The key to diagnosing a freeze-out before it happens is Arman and his invention: the CryoSolid Apparatus. When asked if working with NASA necessitates a sexier name for his creation, Arman just laughs. Perhaps that’s because it’s already ‘sexy’ enough: Australia’s 2019/20 LNG exports are forecast to top $40 billion.

The CryoSolid Apparatus works like a recording studio for hydrocarbons. You pop a sample of LNG into the spotlight, the temperature drops and the device films the exact point at which the sample begins to freeze. You can literally see it happen. And different amounts of different impurities cause the sample to freeze out under different conditions.

“Once we know what temperature and pressure causes a particular gas composition to freeze out, industry can know what’s going to happen and they can avoid it,” Arman says.

It’s a researcher’s life for Arman

Arman’s research is part of his PhD at the University of Western Australia.

Though he spent a few years in the oil and gas industry, he’s drawn to life as a researcher.

“The stimulation of research and hands-on experimental work is vital to my career enjoyment,” he says. “I found Professor Eric May, who is very well known in this industry. That’s why I decided to do my PhD, to explore more about how we can solve problems in this industry.”

“Never let an opportunity pass by, and never be afraid of failure... If my work can make a difference, so can yours.”

To Titan … and beyond

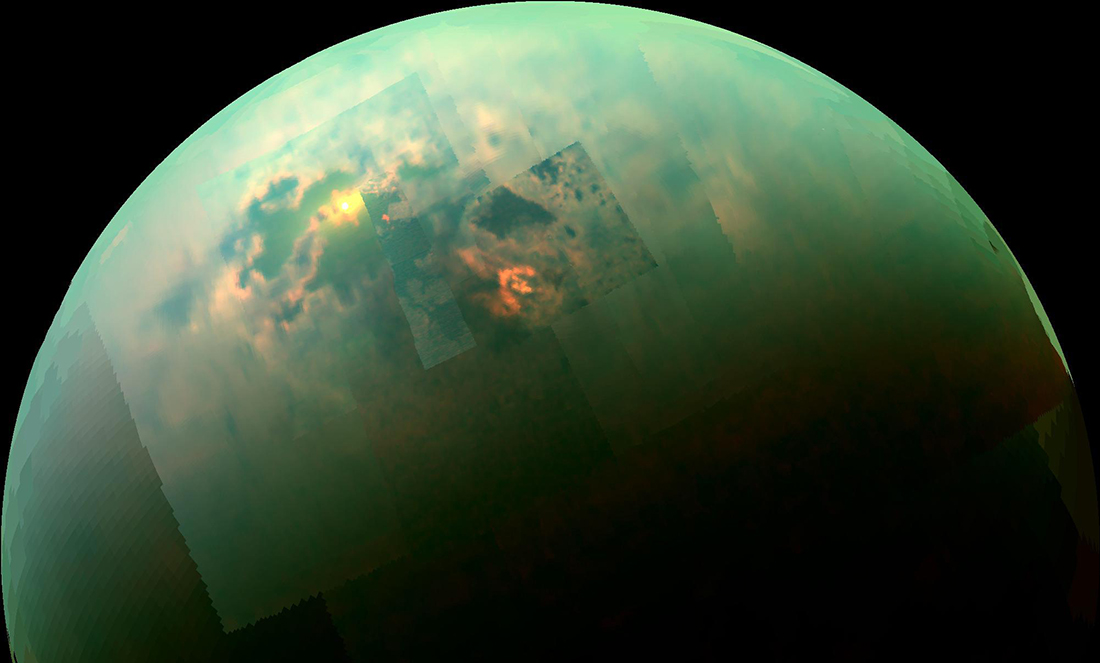

Since NASA caught wind of Arman’s work, he’s spent time at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Turns out the surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, contains lakes and rivers of liquid methane and ethane.

“NASA are interested in knowing how fast organic materials can dissolve in those liquid lakes or rivers,” Arman says. “We showed them that, using our tool, we could measure what they were after.”

Arman doesn’t only have his sights set on the Solar System. He’s also keen to adapt his technology to medicine. “It’d be cool to have a tool to predict heart attacks well in advance,” he says. “Blood can be treated as a fluid as well. Hopefully, one day, we can use this method to find a tool to predict heart attacks.”

Arman says he’s thrilled with his win at the Premier’s Science Awards, and he’d like other researchers to join him. “Never let an opportunity pass by, and never be afraid of failure,” he says. “If my work can make a difference, so can yours.”