Since it launched in 2004, Facebook has been working to “give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected.”

This sounds great. But is it, actually?

Does connecting with everyone you’ve ever met ever on Facebook make you happy? Does sharing everything with them on Facebook make you jump out of your seat with joy? Probably not.

In fact, if the research is any indication, you may actually be finding Facebook and other social media sites aren’t so great for your mental health. Instead of feeling blissfully open and connected with your friends, you feel inadequate or maybe even a bit depressed.

Is social media making us sad because technology is inherently alienating? Is Facebook actually just evil?

We’ve been asking questions about technology like this for a rather long time. But the answer is a bit more complicated.

Ye olde internet

If you were an internet researcher in the 1990s (when the internet was first going mainstream), you would have been aware of two key ways of imagining the future: utopian and dystopian.

In their 1998 review of the literature, British researchers Debra Howcroft and Brian Fitzgerald summarised these two strands and the internet’s predicted impact on the world.

In the utopian vision, the internet was not only “the gateway to a new era of democracy, equity, plenitude and knowledge” but would also “liberate interpersonal relationships from the confines of physical locality and create opportunities for new personal relationships and communities”.

Sound familiar? It sure sounds like a fancy version of Facebook’s mission statement: to bring the world closer together.

In the dystopian vision, on the other hand, “technology exacerbates human misery as individuals become increasingly controlled by what they fail to understand.”

Fake news anyone?

And, as they go on, online relationships could be described as “shallow, impersonal, and often hostile.”

This may also seem familiar and perhaps more in line with today’s lived experience of social media.

So is that it? Were the techno-dystopians right and the reason Facebook makes us depressed is simply because it’s the nature of the internet to cause misery?

It depends. Let’s look at some more clues.

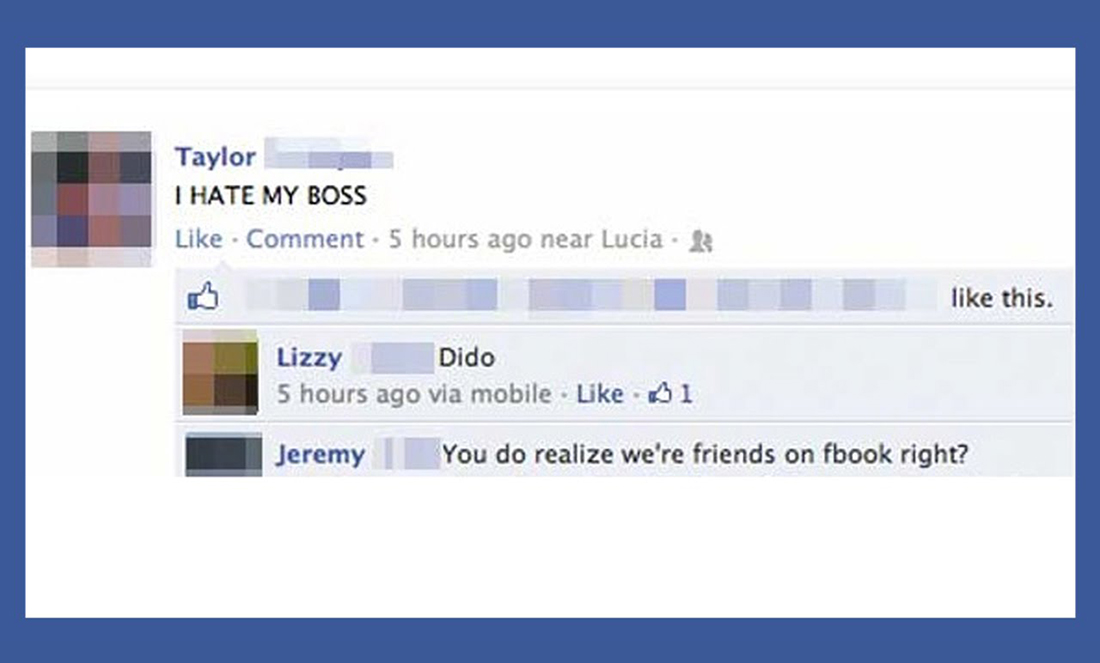

Context collapse

If you were using Facebook back then, you may remember the drama created as the site’s design started making people share more and be less private.

Once a largely locked-down site only for college and university kids (and thus populated with large numbers of photos featuring drunken antics), Facebook became open to everyone in 2006.

The trouble it caused went like this.

In everyday life, we tend to have different sides of ourselves that come out in different contexts. For example, the way you are at work is probably different from the way you might be at a bar or at a church or temple.

Sociologist Erving Goffman used concepts of theatre to explain these different aspects of our identities, for example, front stage and back stage.

But on Facebook, all these stages or contexts were mashed together. The result was what internet researchers called context collapse. People were even getting fired when one aspect of their lives was discovered by another (i.e. their boss!).

Meeting Mark Zuckerberg

In 2008, I found myself speaking with the big boss himself, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. I was in the second year of my PhD research on Facebook at Curtin University. And I had questions.

Why did Facebook make everyone be the same for all of their contacts? Was Facebook going to add features that would make managing this easier?

To my surprise, Zuckerberg told me that he had designed the site to be that way on purpose. And, he added, it was “lying” to behave differently in different social situations.

Up until this point, I had assumed Facebook’s socially awkward design was unintentional. It was simply the result of computer nerds designing for the rest of humanity, without realising it was not how people actually want to interact.

The realisation that Facebook’s context collapse was intentional not only changed the whole direction of my research but provides the key to understanding why Facebook may not be so great for your mental health.

Your perfect self

The key to understanding social media depression lies in the social norm that has emerged around how we manage Facebook’s context collapse in a way that is acceptable in all contexts. That social norm is being your perfect self. And the consequence of that is we are all performing our perfect selves, thus all making each other feel depressed and inadequate.

It didn’t have to be this way

Before Facebook, there were many other sites that did similar things but in a different way. My favourite was LiveJournal (which still exists in a different incarnation, but that’s a whole other story).

In its heyday in the early 2000s, LiveJournal had a strong privacy culture. People used pseudonyms and avatars rather than their ‘real selves’, which was the norm on the internet before Facebook came along.

Before I began research on Facebook, LiveJournal was the focus of my research. I found that the site culture fostered vulnerability, authenticity and mutual support. People would share the highs and the lows of their lives with each other.

LiveJournal was also run as an open source community project rather than a for-profit venture—users were the customers rather than eyeballs to sell to advertisers.

This alternate social media culture shows that social media can be (and was) different. It can support mental wellness rather than harm it.

Peak social media depression?

BJ Novak (who fans of the American version of The Office will recognise) just launched an app called Kiyo, whose tag line is “let’s just be ourselves again.”

The app’s mission sits in stark contrast to Facebook’s goal of connecting everyone, always. As the app’s description on ProductHunt reads:

“engage meaningfully with the people who mean something to you.”

Perhaps we’ve reached peak toxic social media culture, and we’re about to turn a corner.