Innovative Japanese researchers have developed earmuffs (or should that be beermuffs?) that can tell how drunk you are.

The earmuffs can measure blood alcohol concentration in real time like a roadside breathalyser.

They work because our ears give off alcohol fumes in the same way as our breath.

Sounds like you’re over the limit, sir

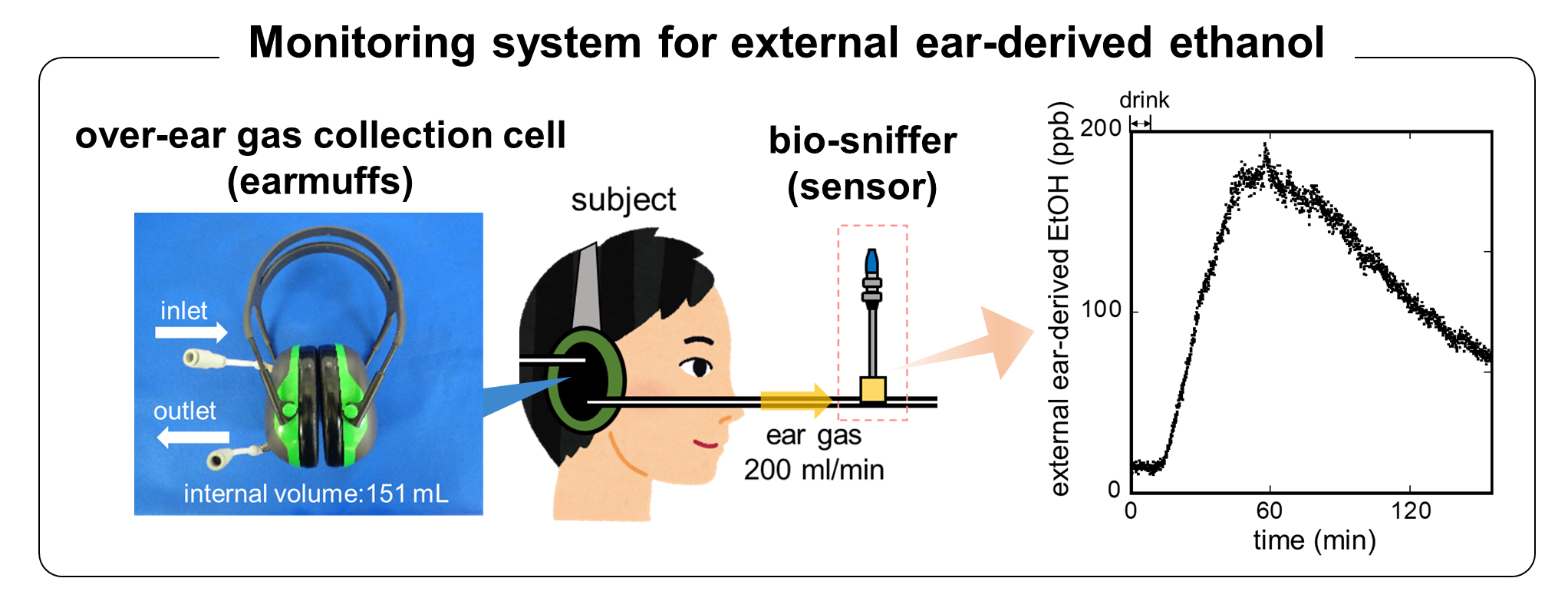

In what’s surely a contender for the Ig Nobel Prizes, scientists at Tokyo Medical and Dental University modified a pair of commercial earmuffs to collect gas released from the skin of a person’s ears.

The earmuffs are attached to an ethanol vapour sensor called a ‘bio-sniffer’. The sensor lights up if it detects ethanol vapour.

The brighter the light, the more plastered you are.

“Getting lit” for science

The scientists recruited three volunteers to test the earmuffs by drinking 0.4g of alcohol per kilogram of bodyweight.

That’s about three standard drinks for someone who weighs 80 kilos.

They used the earmuffs to monitor the alcohol vapour released from volunteers’ ears for a little over 2 hours.

They also measured the alcohol concentration of the volunteers’ breath at regular intervals.

The ears have it

It’s not the first time the Japanese research team has tried to find an alternative to the breath test.

A previous study measured alcohol in gas released from the skin of the hand, but the results changed depending on what part of the hand was measured.

Plus gas from the whole hand contained about 1000 times less alcohol than an exhaled breath.

Other challenges include interference from sweat and the thickness of skin on different parts of the body.

The researchers say ears are good because they have relatively few sweat glands.

It’s also possible that compounds like ethanol in the middle ear are released through a membrane to the external ear canal.

An alternative to the breath test?

In the earmuff study, the ethanol concentration of gas released by the ears peaked at 148 parts per billion on average.

That’s double the concentration of gas released through the skin of the hand.

Changes in ethanol concentration released through the volunteers’ ears and breath were pretty consistent.

However, ethanol readings from the earmuffs peaked about 13 minutes later than those from a breathalyser.

These results led the researchers to suggest ears are a good non-invasive way to measure blood alcohol concentration.

So could you be putting on a pair of earmuffs instead of breathing into a tube on your next drive home from the pub? Not yet, but maybe one day.

Disease screening

The scientists say their invention could potentially be used to screen for diseases.

It comes after Sydney researchers developed a breath ketone analyser that could replace pinprick testing for people with type 1 diabetes.

Another Aussie invention claims to rapidly analyse a person’s breath and detect volatile organic compounds linked to 22 different diseases, including diabetes, asthma and some lung cancers.

If earmuffs work the same way, it could take hearing protection to a whole new level.