If you take a radio telescope and point it at a certain spot in the constellation of Cygnus, you’ll be in for quite the show.

Almost 8000 light years away, there’s a star system called V404 Cygni. It’s a binary system made up of two stellar objects orbiting each other.

One is a young K class star, with a mass slightly smaller than our Sun.

Its partner is a black hole—leisurely stealing fuel and turning the neighbourhood into a disco.

Astronomers have been keeping an eye on this pair of objects since 2015, when NASA’s Swift Observatory spotted them flashing—an event known as a nova.

This week, astronomers have announced this odd pair have another unusual characteristic—the black hole wobbles like a spinning top.

V404 – star not found?

While there are many unusual objects in our night sky, V404 stands out for a few scientific reasons.

First, it’s a variable star meaning its light fluctuates over time, becoming brighter then darkening over time.

It’s also classified as a nova, producing bright bursts of energy, that have been spotted on three occasions since 1900. As you’d expect, a nova is a smaller explosion than a supernova. These explosions have only been observed in binary systems so far, usually when stars are so close they’re almost colliding.

And finally, it’s also classed as a soft X-ray transient (SXT)—a very rare object that occasionally sends out short bursts of X-ray radiation.

With so much going on at V404, it has captured the interest of astronomers around the world.

One of those teams is from the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) here in Perth.

You spin me right round

Associate Professor James Miller-Jones from ICRAR’s Curtin University node is the lead author of the new research for V404.

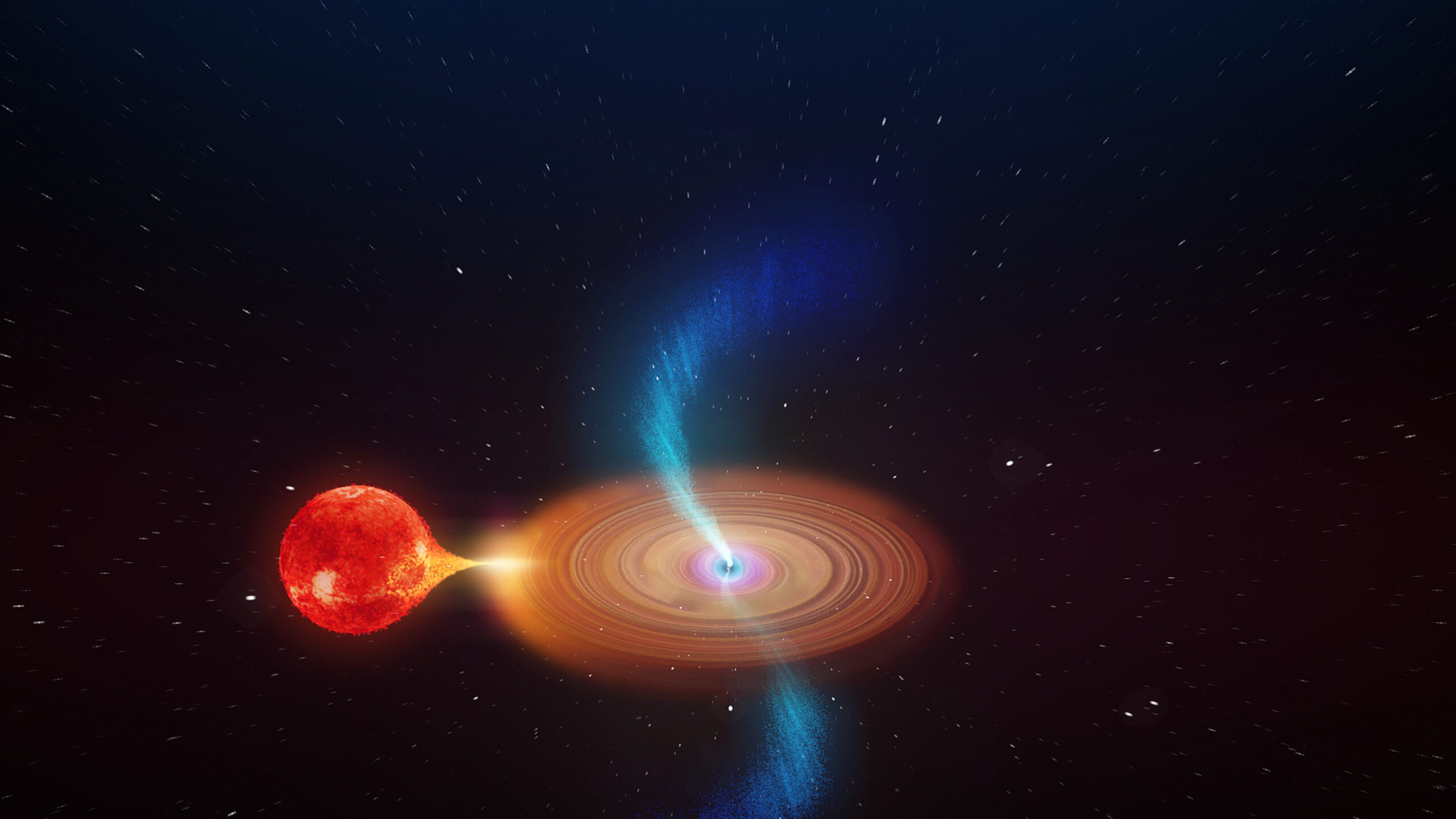

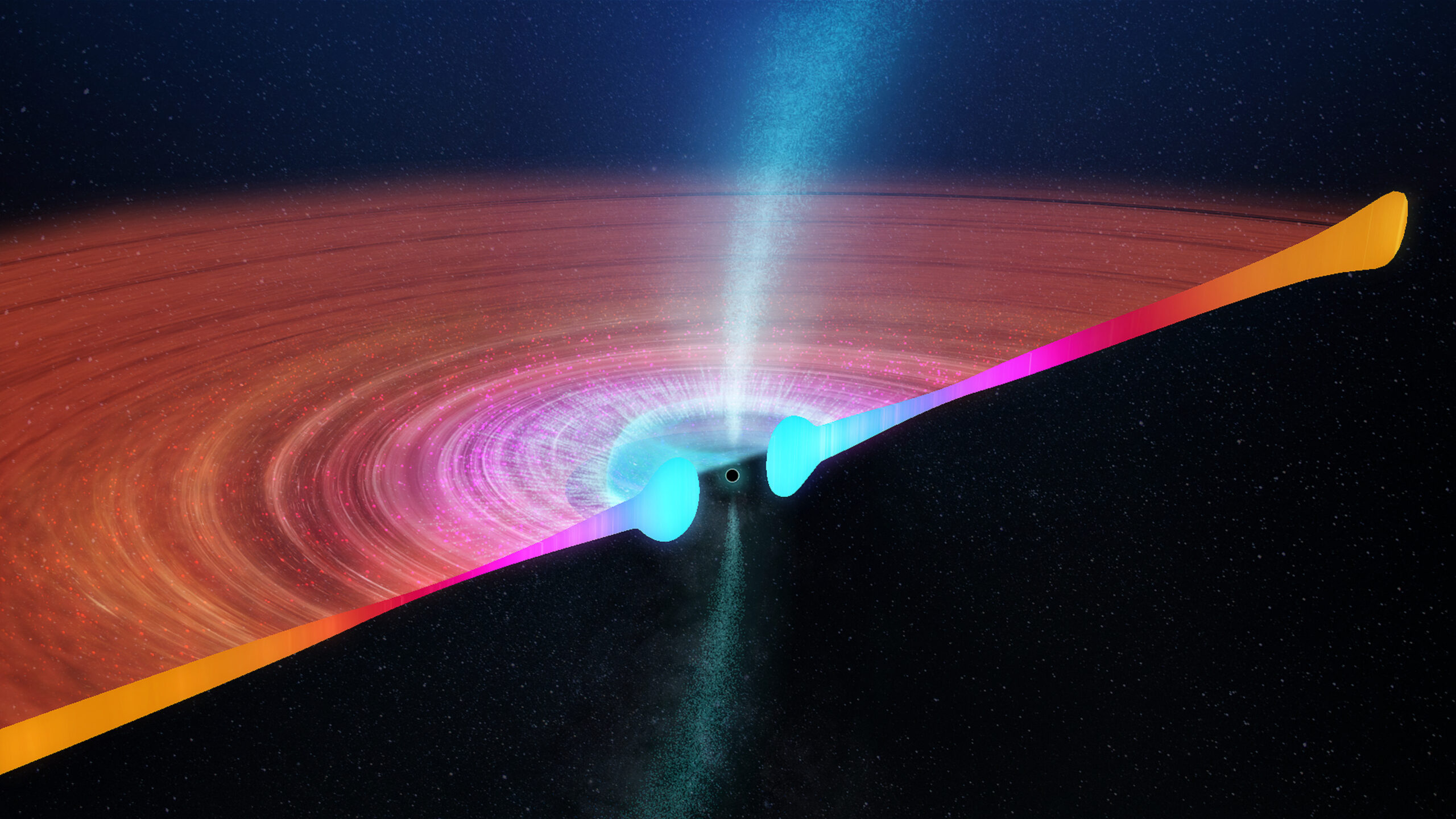

“Like many black holes, it’s feeding on a nearby star,” he says. “It’s pulling gas away from the star and forming a disc of material that encircles the black hole.”

“What’s different in V404 Cygni is we think the disc of material and the black hole are misaligned.”

Some black holes have jets of ionised matter ejecting from their poles, accelerating particles to close to the speed of light.

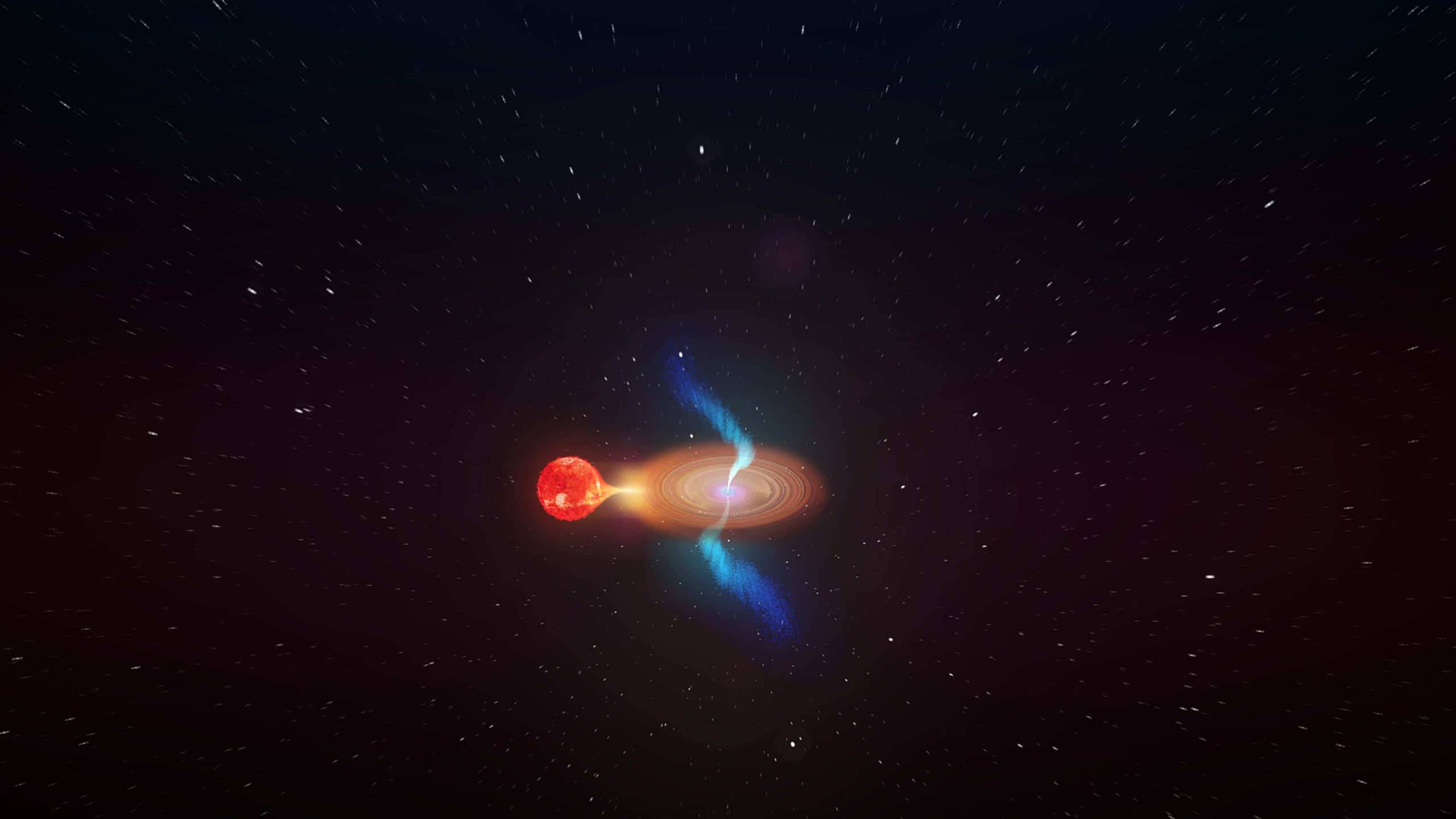

These beams of matter don’t tend to move around very much, but in V404’s case, they are changing direction over the course of a few hours.

James says the movement is because of the accretion disc—the rotating disc of matter found around a black hole.

“The inner part of the accretion disc is precessing [a slow and continuous change in rotation] and effectively pulling the jets around with it,” he says.

“You can think of it like the wobble of a spinning top as it slows down—only in this case, the wobble is caused by Einstein’s theory of general relativity.”

“This is one of the most extraordinary black hole systems I’ve ever come across.”

Blurry photos

With these jets wobbling and spinning so fast, it’s hard to take a decent image using a radio telescope.

Radio telescopes rely on a long exposure to take an image— usually several hours. But in that time, V404’s beams will have spun to a different location, leaving nothing but a blur.

University of Alberta PhD graduate Alex Tetarenko is a co-author of the paper. Working in Hawaii as an East Asian Observatory Fellow, she says taking the image required the team to think outside the box.

“It was like trying to take a picture of a waterfall with a 1-second shutter speed,” she says.

Instead of the usual long exposure, researchers took 103 images with a 70-second exposure each, before joining them together into a movie.

Black hole fever

Another of the studies co-authors, Dr Gemma Anderson, is based at ICRAR’s Curtin University node. She believes the wobble of the accretion disc could explain other extreme events in the universe.

“That could include a whole bunch of other bright, explosive events in the universe … such as supermassive black holes feeding very quickly or tidal disruption events when a black hole shreds a star.”

The team has published their full research paper in the journal Nature.

Their research will help us to better identify what’s happening in our night sky—especially when it comes to one of the universe’s most unusual cosmic creations.