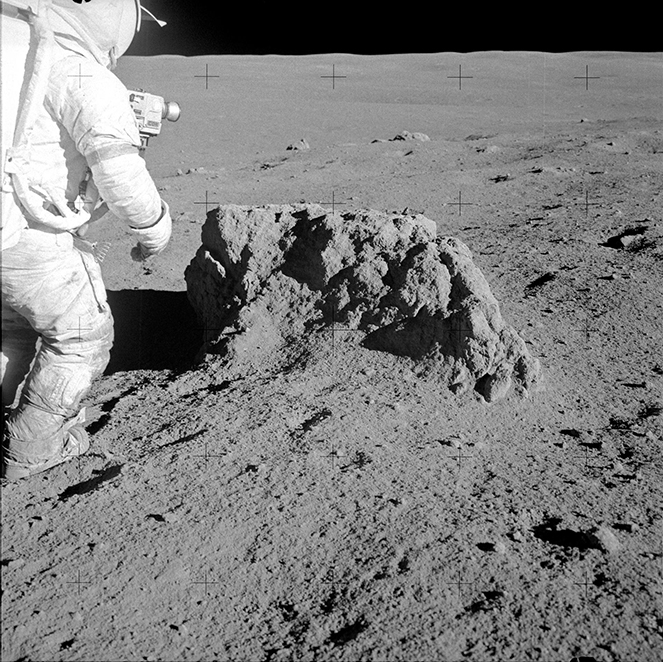

If you put a Moon rock alongside one from Earth, they usually don’t have a lot in common.

So when Curtin University planetary scientist Professor Alexander Nemchin looked closely at a Moon rock in his laboratory, he realised something wasn’t right.

The rock’s composition was similar to granite, which is extremely rare on the Moon but fairly common on Earth.

Stranger still, the 1.8 gram rock also contained quartz. And the zircon in the sample was very different to every other rock analysed from the Moon.

“This particular piece – there is nothing similar to it in the rest of the 400 kilograms of samples, not at least that we’ve found so far,” Alexander says.

Chemically, it looked less like a typical Moon rock and more like some of the oldest rocks on Earth.

Lost in space

The rock in question is on loan to Curtin University from NASA.

And it definitely came from the Moon – the Apollo 14 astronauts collected it in 1971.

But Alexander’s team discovered something no one else had picked up on for almost half a century.

This rock was probably flung to the Moon from Earth roughly 4 billion years ago.

“We find lunar meteorites on Earth, so there is an exchange of rocks. It certainly happens,” Alexander says.

“Especially considering that, 4 billion years ago, the Moon was much closer to the Earth, so this exchange would be much more efficient.”

Planetary rock tossing

Alexander says this particular rock likely landed on the Moon after an asteroid hit the Earth and launched it into space.

So why were Alexander and his team the first to work it out?

“Usually these things happen out of nowhere,” he says.

“You just look at the sample or set of data and suddenly realise that there is the possibility of a certain interpretation.”

“Even though, sometimes 50 people looked at the same dataset or the same sample before.”

Alexander was able to access the Apollo 14 sample due to a NASA decree dating back to the 1970s – the returned rocks belonged to the whole world.

Scientists can access the lunar samples by applying to NASA with a detailed proposal of the research they want to conduct on the rocks.

Curtin has been lucky to access several Apollo samples over a decade of research on Moon rocks, Alexander says.

Chinese mission to the Moon

Alexander is currently in China, laying the groundwork for any lunar samples returned from the Chang’e 5 mission to the Moon.

He says there’s a lot of preparation to be done before any rocks arrive.

“It’s a complicated procedure,” he says. “Before you even start doing research, you need to open the samples and it takes quite [a long time].

“You need to follow specific protocols so you don’t contaminate your samples.”

For Alexander, lunar research is one area where human beings can work together to solve problems, regardless of borders.

“It has this profound impact on people in creating an ability to collaborate, at least on something.”