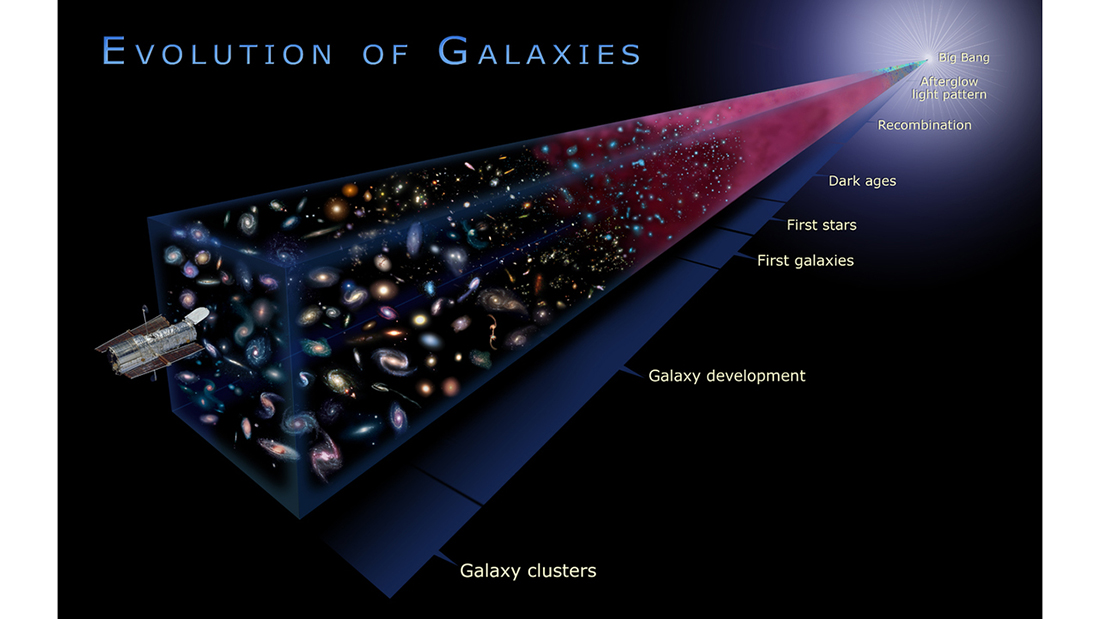

Astronomers are on the search for a mysterious signal. This signal could chart the universe’s first stars and tell us how existence took shape.

Light travels nearly 300 million kilometres per second. It’s the fastest thing in the universe.

Even at this speed, it takes roughly 25,000 years for light to travel from the edge of our galaxy to Earth.

This means that, when we point telescopes at the edge of the galaxy, we’re actually seeing it as it was 25,000 years ago. The further out you look, the further back in time you see.

Birthing a star

Professor Cathryn Trott is an astronomer at the Curtin Institute of Radio Astronomy.

Cathryn is trying to sneak a peek at how the early universe looked by observing the space between galaxies.

Faint traces of radiation left from the formation of stars and galaxies still linger. As this radiation hits Earth, we can learn about our universe’s history.

“The early universe was filled with a fog of neutral hydrogen gas,” says Cathryn.

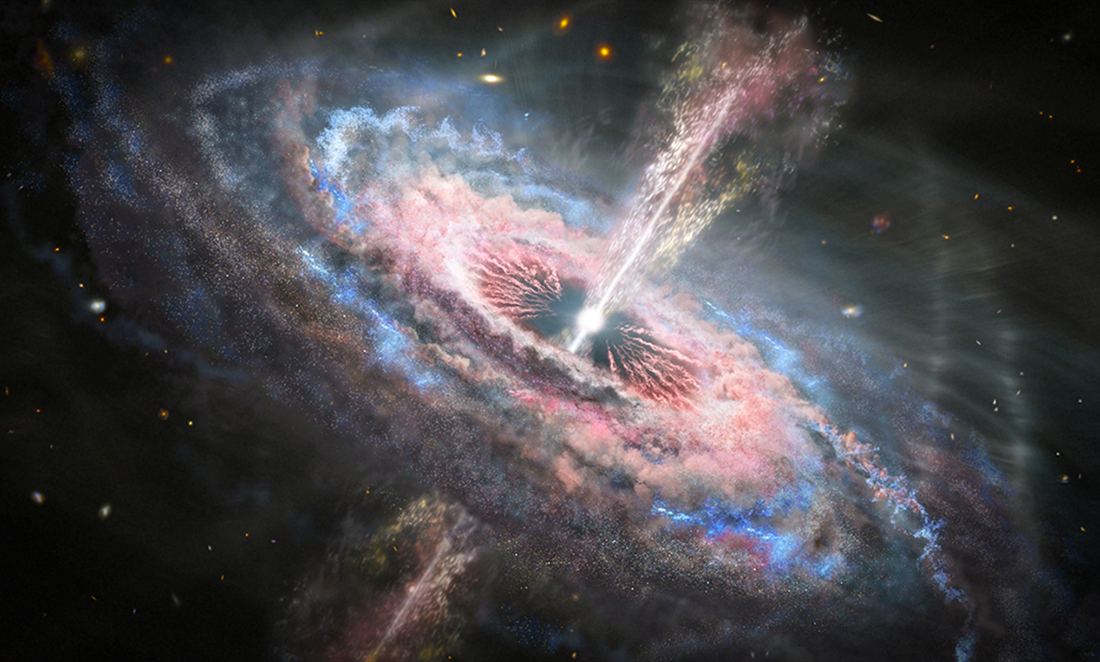

“When the first stars and galaxies formed, they produced ionising light. This light was energetic enough to strip away the electrons from the protons. That’s exactly what it did to this neutral hydrogen fog.”

Neutral hydrogen emits radiation at a very specific wavelength. Looking for this wavelength can show where the neutral hydrogen was in the universe.

Stars and galaxies remove this neutral hydrogen. This means we see how stars and galaxies formed in the early universe by looking for blank spots.

“If we can map radiation as a function of distance, we can walk back in time and see the conditions of the early universe,” says Cathryn.

The neutral hydrogen radiation that hits Earth from the early universe is 10,000 times fainter than the radiation of nearby stars.

This means Cathryn has to look for faint signals in an incredible amount of noise.

The hidden signal

“We eke out this signal by staring at the same patch of sky for a long time. We used the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) over 4 years during specific seasons and integrated the data,” says Cathryn.

Cathryn has combined years of observations looking for this signal. To this day, nobody’s found it, but astronomers are getting closer.

“To detect the signal, part of the problem is we don’t know exactly what the signal is. We don’t know exactly how bright it’s going to be, or exactly know where it will come from,” Cathryn says.

“We have a rough idea about this signal, but our models show it will take 1000 hours of clean data to find it. We’ve published the largest experiment on this and had 110 hours.”

Clean data is the leftovers after Cathryn removes telescope readings of galaxies.

“Western Australia is perfectly poised to do this experiment, because we have the MWA and the future Square Kilometre Array. We also have dark skies and the astronomy expertise here.”

Astronomers expect to find the signal before 2029. It will be the first step in confirming how all the bodies in our known universe formed from a fog of hydrogen gas.