According to a new study, there could be more than 121 places where we should look for signs of life. But we are not talking about new Earth-like planets. Researchers think we should be looking at moons!

“So far, the search for habitable worlds has been focused primarily on finding Earth-like planets in the habitable zone of their star, but this is not the only type of world on which we might find habitable conditions,” says Michelle Hill, a student from the University of Southern Queensland who led the new study.

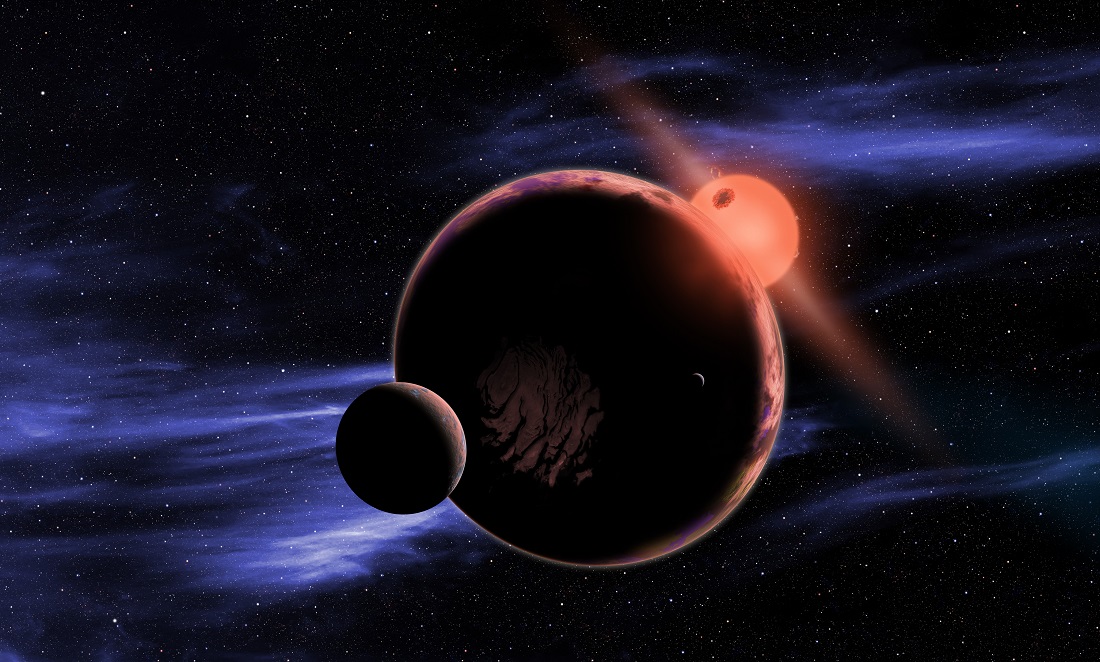

Moons from planets like Jupiter and Saturn are also good places to look for life. And why not? Even our own Moon could host human life one day.

“Just think of Jupiter’s moon Europa. A lot of evidence suggests that this tiny moon hosts liquid water. If I had to guess where we will first find an alien lifeform, I would say it is just as likely on a moon like Europa as it is on a planet like Mars,” says Simon George, a professor of Organic Geochemistry at Macquarie University.

Location, location, location

Much like finding the perfect spot in real estate, finding life in outer space is all about location.

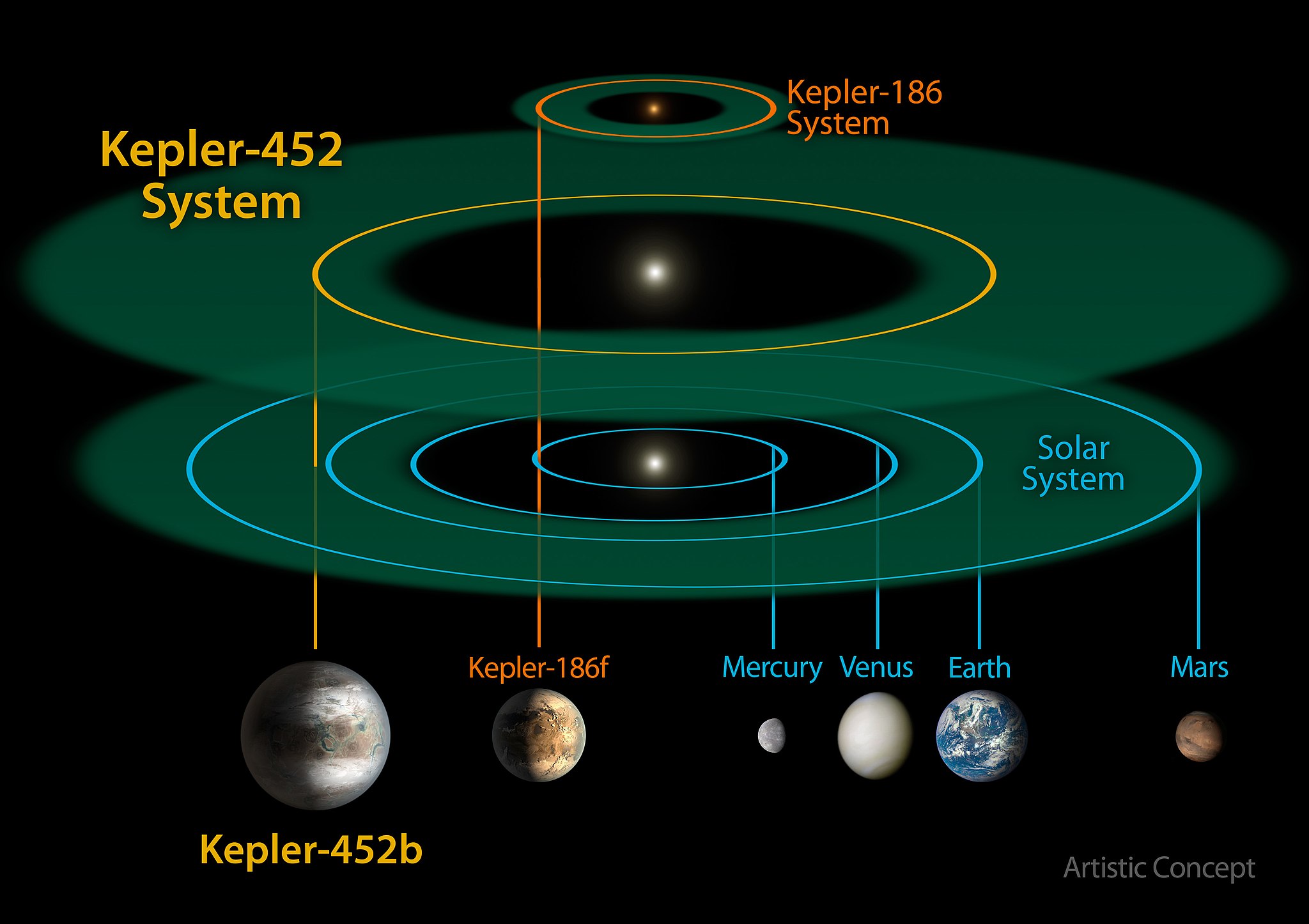

In her new study, Michelle aimed to determine how many potentially life-supporting moons are out there. Her focus was on the so-called habitable zone, where conditions are optimal for the existence of liquid water.

Her data came from NASA’s Kepler mission, which launched back in 2009. The mission is currently searching the Milky Way for signs of potentially life-harbouring planets.

“We don’t really know much about how many moons are in the habitable zones of stars like our Sun,” Michelle explains, “but we do know that many giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn have multiple moons orbiting around them.”

“As our biggest gas giants hold many moons each—Jupiter with 69 moons and Saturn with 62—we expect these habitable zone giant planets would also host many moons that could be potentially habitable worlds,” she adds.

A whole new world

So, if we find out how many of these planets are out there, we can get an idea of how many moons might be orbiting around them.

Michelle’s study found at least 121 giant planets that are found within the habitable zone in our Milky Way galaxy that may harbour life-sustaining moons.

“If we assume each giant planet has many moons, then this study has helped to double or even more the number of potentially habitable worlds that we can observe in the universe,” Michelle says.

“The implications of these findings are that there are many more potential places that life could exist in our galaxy than previously quantified,” Simon says.

“Indeed, considering the expected number of these moons in the habitable zone of their star, it is quite possible that the first signs of life found outside the Solar System, if it exists, could actually be found on a moon rather than an Earth-like planet,” Michelle says.

“The future challenge is how we might go about detecting life, whether it be microbial or higher intelligence,” Simon adds.

Now Michelle plans to continue her search for more interesting moons and planets that may be harbouring life. This will be part of her PhD, which she plans to start soon.

“The search for habitable celestial bodies, such as planets and exomoons in habitable zones is not only about finding alien life. It’s also about giving our children and our grandchildren a place to look towards as they reach for the stars.”