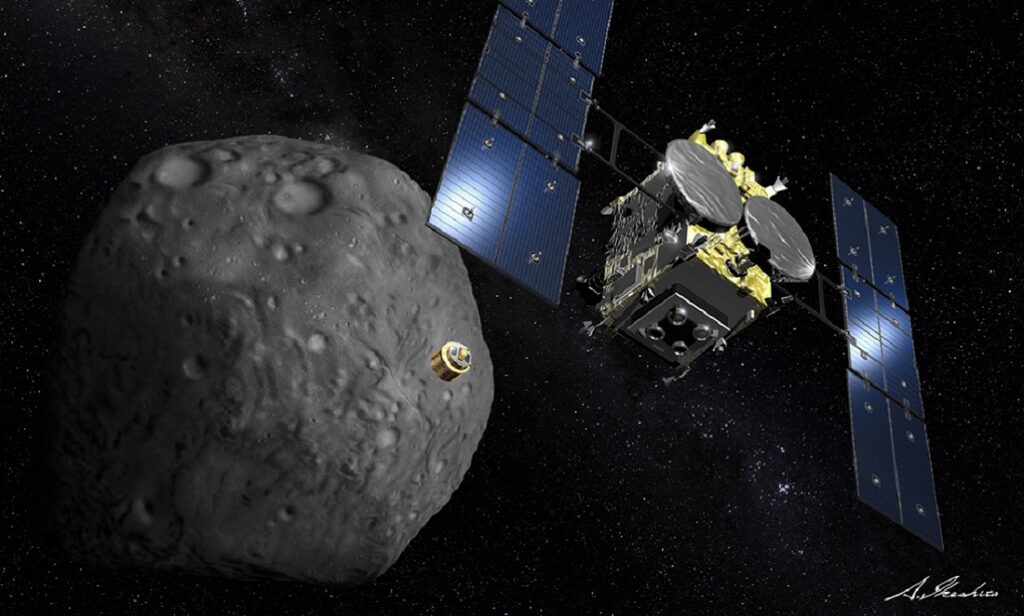

When Japanese space mission Hayabusa2 lands on the asteroid Ryugu mid-year, Associate Professor Fred Jourdan will be watching very closely.

The Curtin University earth and planetary scientist saw the mission launch live in Japan in 2014 and is hoping to score pieces of the asteroid when Hayabusa2 returns to Earth.

He wants to shoot the asteroid samples with a laser beam and vaporise them.

It’s all in the name of discovering more about our Solar System.

RENDEZVOUS WITH AN EXTRATERRESTRIAL ROCK

If Hayabusa2 is successful in collecting fragments from Ryugu, they will be among the most valuable dust particles on the planet.

But Fred and his colleagues have good reason to believe they might be awarded access.

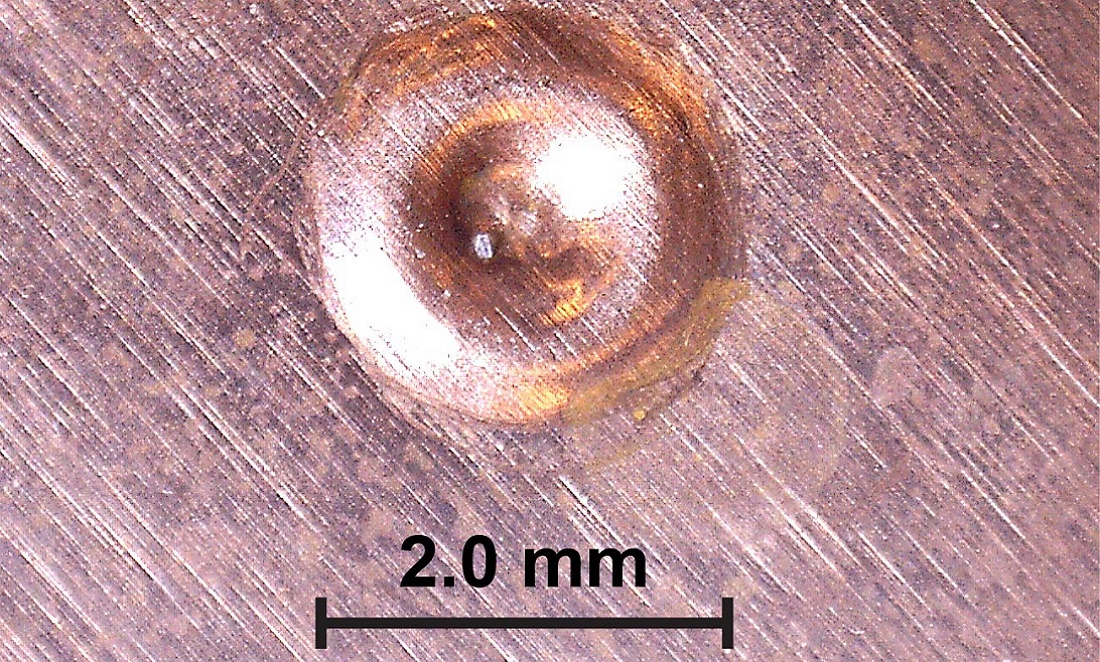

In 2012, the team successfully bid for two grains from the asteroid Itokawa collected by the Japanese space agency (JAXA) mission.

These precious samples—the first and only particles ever collected from an asteroid—were analysed by Fred using specialised equipment at the John de Laeter Centre in Bentley.

“We proposed to date the samples, but because they were so small, there were very few—if any— other labs in the world that could do that,” he said.

“The samples—they are the width of the human hair, they were less than 100 microns, which is very, very challenging.”

A VIOLENT PAST

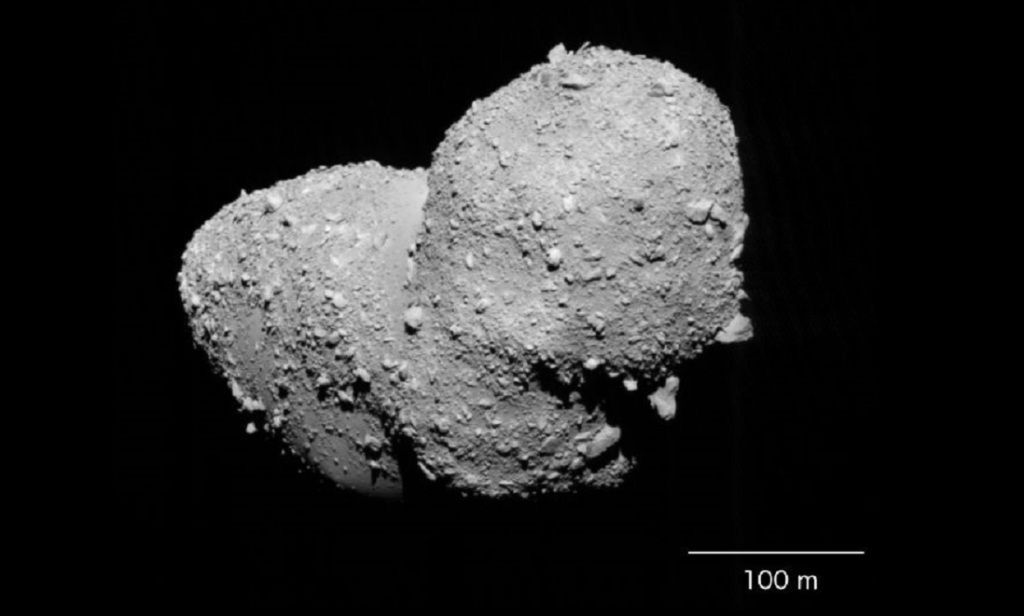

Itokawa is more of a peanut-shaped pile of rubble than a traditional boulder asteroid, and it has a violent past.

Fred’s research, published last year, showed that the asteroid was likely battered by a series of collisions that caused it to internally fragment.

One final impact caused the asteroid to shatter.

Fred’s success meant he was awarded four more samples from Itokawa, despite the fact that he destroyed the first two.

“So those two grains, they’ve been lasered to oblivion, but JAXA were OK with that. It’s not like we didn’t tell them.”

“The argon-argon technique, which dates the sample, needs to completely vaporise and fuse the sample to release the gas that is trapped inside,” he said.

“So those two grains, they’ve been lasered to oblivion, but JAXA were OK with that. It’s not like we didn’t tell them.”

THE WAITING GAME

JAXA says Hayabusa2 has a lofty goal to “elucidate the secrets of the creation of life and the birth of the Solar System”.

(No pressure Fred.)

But it will be a couple of years before we know if the mission to Ryugu is successful, with the return samples due back on Earth at the end of 2020.

Fred is also hoping a collaboration with China might mean he can get his hands on new samples from the Moon.

In the meantime though, he’ll have to entertain himself with more earthly dust fragments.

“I’m very interested by volcanoes and eruptions and lava flows, so I have PhD students working in different volcanic provinces around the world,” Fred says.

“We’re working on the relation between large volcanic eruptions in the past and previous mass extinctions.”

The John de Laeter Centre is a collaborative research venture involving Curtin University, UWA, the Geological Survey of WA and CSIRO.