In late October, NASA announced astronomers had found ice on the Moon’s surface! But wait, didn’t we already know that? And why should Australia care?

Well, we knew there was ice on the Moon’s north and south poles, but the rest of the Moon’s surface was a mystery.

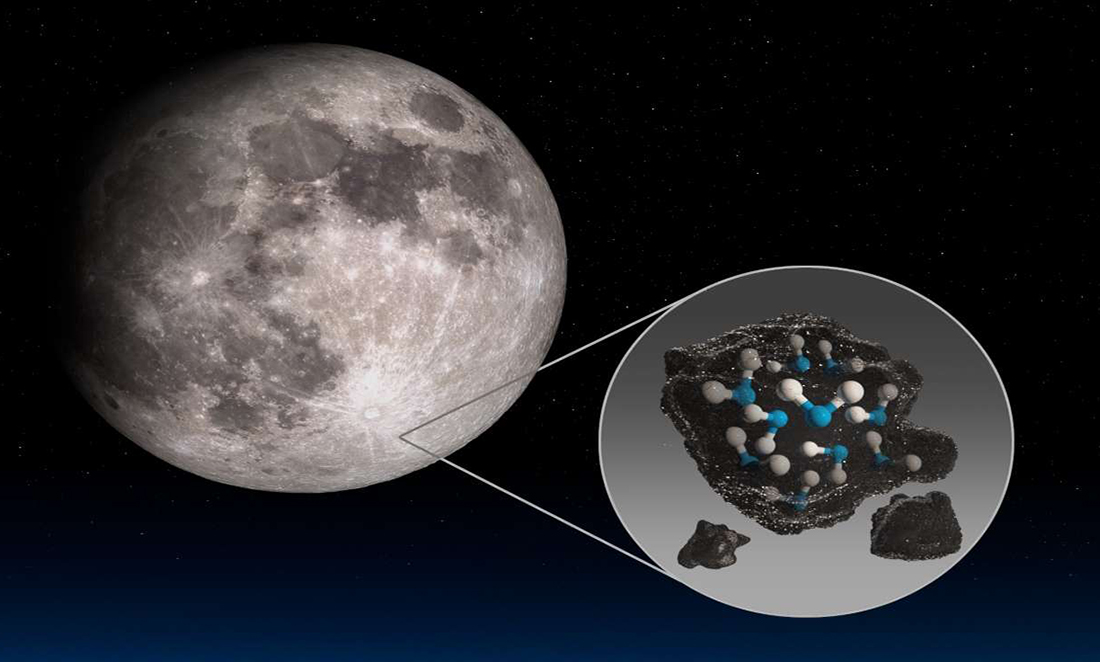

Astronomers knew about water-like molecules on the surface, but they weren’t sure if this was H2O or the molecule OH-, which acts like drain cleaner.

Ice, ice baby

The NASA announcement was based on two scientific papers.

The first paper used a NASA jet called the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).

SOFIA picks up the infrared light the Moon gets from the Sun and reflects to Earth.

Each molecule has a unique way of reflecting light. By studying the infrared light from the Moon, we can tell what molecules are on its surface.

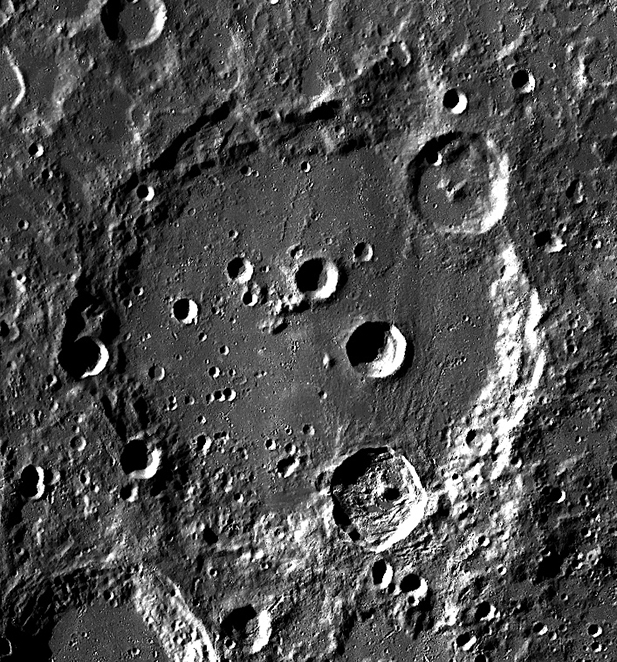

A team of astronomers using SOFIA found H2O molecules on the Moon’s sunny surface by mapping one of the Moon’s biggest craters, Clavius.

SOFIA found roughly enough ice to melt and fill one 360mL bottle per cubic metre.

At the same time, another group discovered ice in crater shadows.

Sunny side up

Dr Sascha Schediwy is a space scientist who studies the Moon. He was hyped when NASA announced news of water on the Moon’s sunny side.

Sascha leads the ICRAR/UWA Astrophotonics Group in Western Australia. This group uses light in different ways to study space.

“It’s a really exciting find. It makes human exploration of the Moon more compelling,” Sascha says.

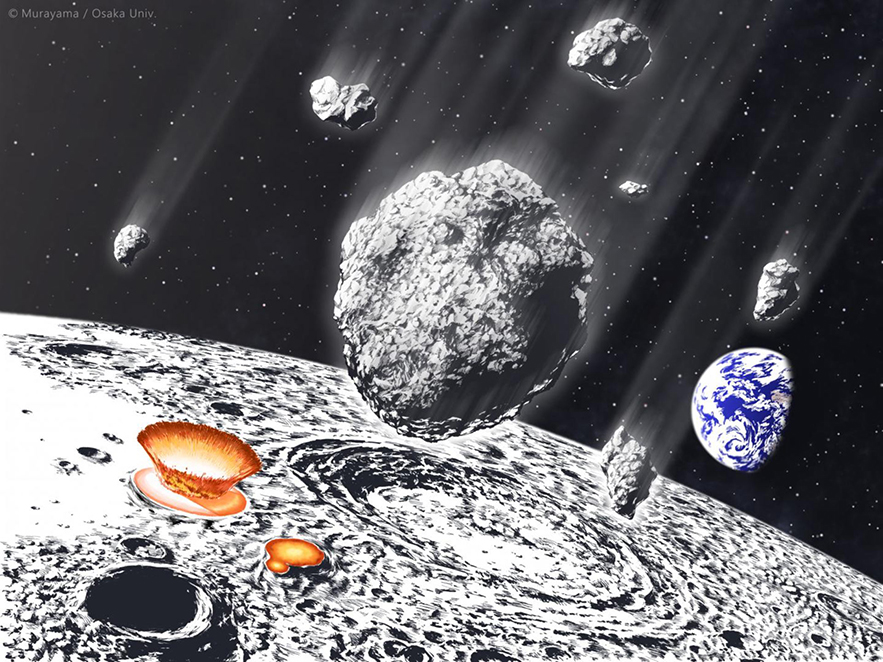

What’s amazing about these findings is that astronomers long thought water ice couldn’t exist on the Moon’s sunny surface.

“Micrometeor impacts and solar wind would evaporate surface ice. That we detected some even though we shouldn’t be able to means there might more beneath,” says Sascha.

The Moon’s sunny surface is also 127°C. That would boil water on Earth, but the Moon doesn’t have an atmosphere.

This means shadows stay cool enough for ice, while areas nearby are roasting.

Quench your thirst with space water

So why is ice on the Moon important?

Astronauts can drink the water, use it to protect against radiation and turn it into rocket fuel. A large ice deposit on the Moon is like a goldmine on Earth.

NASA plans to build a Moon outpost starting in 2024, and they’ll need water to do it.

Australia’s trip to the Moon

Australia will be involved by building launch pads and monitoring stations.

“Australia should be involved in Moon settlement. We have a geographical advantage in the southern hemisphere. That’s important for activities on the Moon’s south pole,” says Sascha.

The Australian Government has set aside a fund of nearly $20 million this year for space businesses.

Sascha says Australia should send its own microsatellites to explore the Moon. These satellites could find more outpost sites and expand our space industry.

Discovering ice on the Moon’s surface means we’re one step closer to humanity exploring and settling the Solar System.

I guess this makes ice pretty cool!