You’re driving down the freeway listening to the radio. Unfortunately, the radio is picking up some static. Sounds a bit rough, doesn’t it?

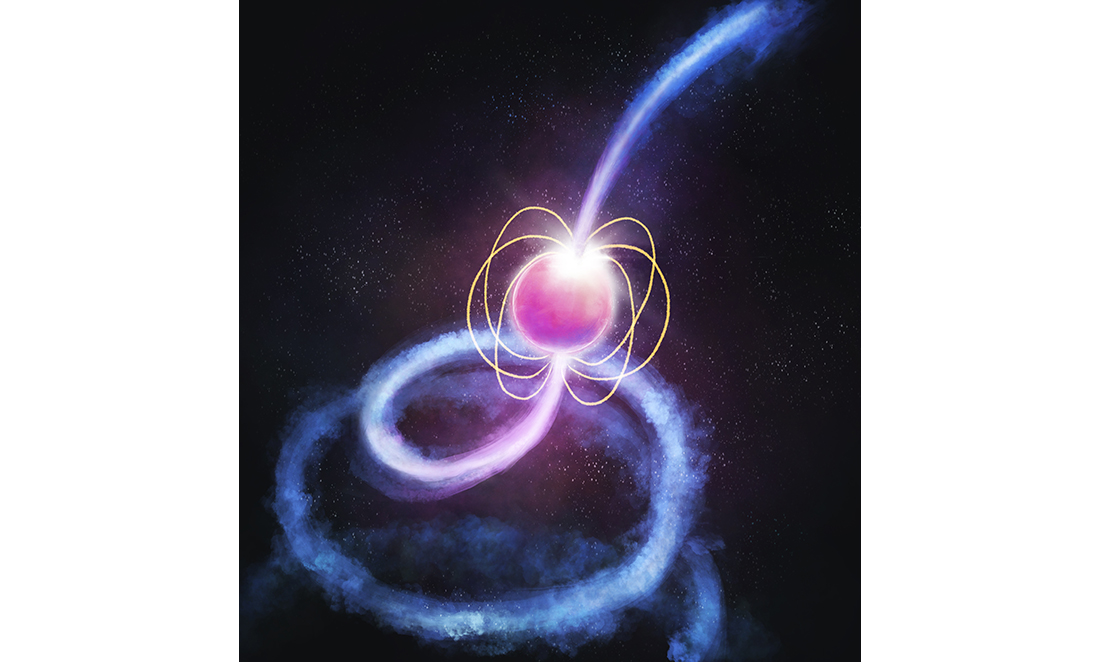

It may surprise you to learn that static is actually the grand opera of the universe – stars, pulsars, galaxies – all of which blast out radio waves and have been doing so for billions of years.

Yup, the car radio in your 2002 Honda Civic is tuned in to the universe, man.

But while we all may be able to tune in to Cosmic FM, not all of us can make sense of the noise.

That’s where Professor Steven Tingay comes in. He’s the Executive Director of the Curtin Institute of Radio Astronomy at Curtin University and Deputy Executive Director at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, a joint venture between Curtin University and UWA. And his team has found some pretty cool stuff in that static.

Turning the cosmic dial

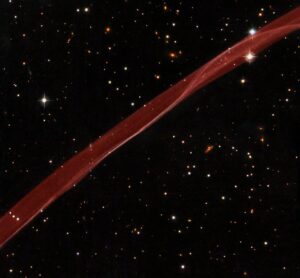

Using the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) telescope, a cutting-edge radio astronomy tech, Steven’s team has discovered a pulsar – a dense and rapidly spinning neutron star that pulses radio waves out into the universe.

While this is the first pulsar detected by the MWA, which is situated in Western Australia’s remote Mid-West region, it’s sure to not be the last. Indeed, this find shows how many of today’s great discoveries aren’t made by travelling to new worlds but by just listening to what’s already around us.

As Steven explains, “Each MWA antenna receives radio waves from all parts of the sky – all objects simultaneously, 24/7.

“They’re taking in 100% of the information the universe is giving us in radio waves.”

Yet you may be wondering, if your car radio can pick up radio waves from the universe, what makes the MWA so cutting edge?

Chunky data

Tuning in to Cosmic FM is only the first step. The hard part is crunching the numbers.

“Once the MWA collects data, you need to process those data in different ways to extract different bits of information about different objects,” says Steven.

“We can turn the radio waves into an enormously rich dataset, and you can process those data in lots of different ways to learn different things … as long as you can afford the computing power.”

Indeed, if there is something limiting radio astronomers, it’s not their ability to pick up information. It’s the ability of computers to actually process the huge amounts of data.

So far, the MWA has collected about 40 petabytes of data – that’s equivalent to 40 million gigabytes. And if you thought that was big, say hello to the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) …

Hip to be square

One of the largest scientific endeavours in history, the SKA is a telescope with a lens of – you guessed it – a square kilometre. Although, importantly, it’s not one lens. It’s thousands of tiny lenses scattered across the world, from high-frequency dishes in South Africa to smaller low-frequency antennas in WA.

“The MWA is comprised of 4000 individual antennas in WA, whereas the SKA will be comprised of more than 130,000 individual antennas in WA spread out over 120km.”

“The SKA will be much more sensitive than the MWA and will be able to make images in much finer detail.”

“MWA is 1% of what the SKA will be.”

The final frontier

That’s going to be a lot of data to crunch, but Steven is looking forward to using this incredible tool to ‘explore’ the last unexplored epoch in the universe’s evolution: its first billion years.

“Within that first billion years, the first generation of stars and galaxies formed, setting the scene for the evolution of the universe.”

Unlocking the mysteries of the first billion years of the universe? Let’s see your 2002 Honda Civic do that!

So next time you’re driving down the freeway and can’t quite tune in to the cricket, just sit and enjoy the static for a moment. You’re listening to the biggest radio show in the universe, and it’s all about how we got here.