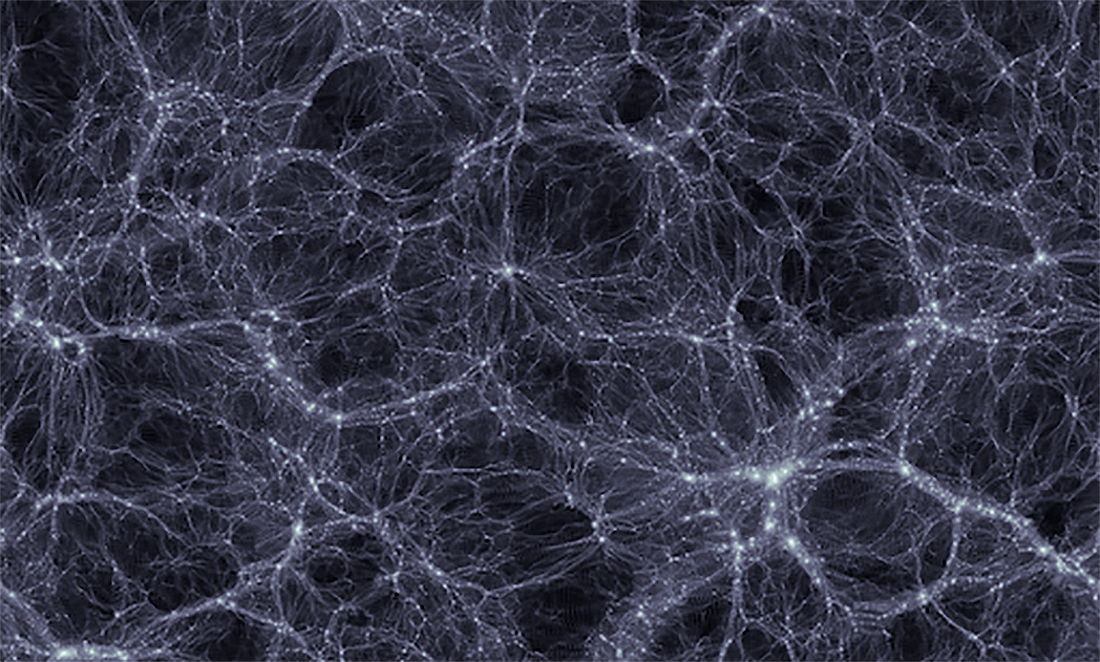

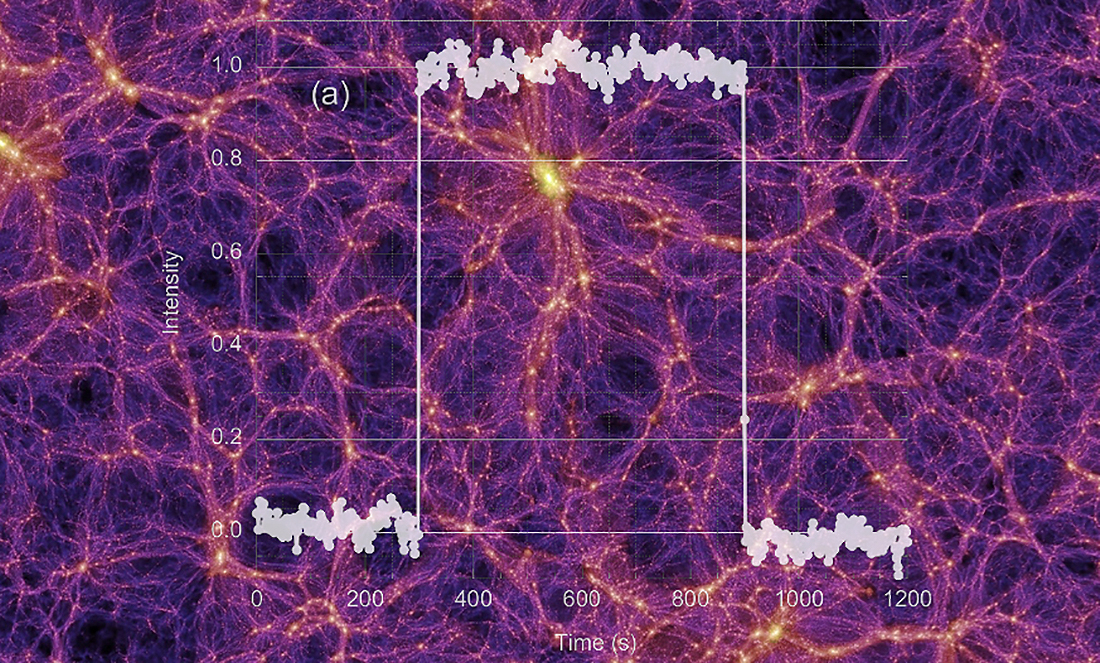

Also known as weakly interacting massive particles, WIMPs are a theoretical particle of dark matter—the mysterious stuff that accounts for 85% of the mass of our universe.

We know dark matter is out there, we’ve just never detected it directly.

“Dark matter is one of the greatest mysteries in physics,” says Stephen Derenzo, researcher at the US Department of Energy’s Berkeley Lab. “Its existence has been confirmed by many astronomical observations through its gravitational force on stars, galaxies and light rays.”

But what we want now is physical evidence that dark matter exists. That’s why we’re searching for WIMPs.

But what if we’re searching for the wrong thing?

The name WIMP implies “massive” size, but we’re really talking subatomic particles. Specifically, something heavier than a proton.

We’ve been searching for WIMPs above the proton mass for a while, using a “large number of huge experiments … but no signals have been confirmed,” says Stephen.

So what if WIMPs aren’t this size at all? “Nothing is known about their mass, and they could be much lighter,” Stephen says.

If we want to search for lighter WIMPs, we’ll need a way to detect much smaller signals. We’ll need a detector that can respond to energies thousands of times lower than what we’ve been expecting.

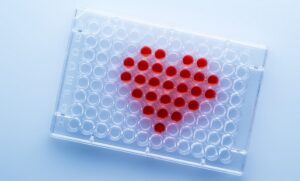

That’s where GaAs comes in.

Gallium arsenide to the rescue

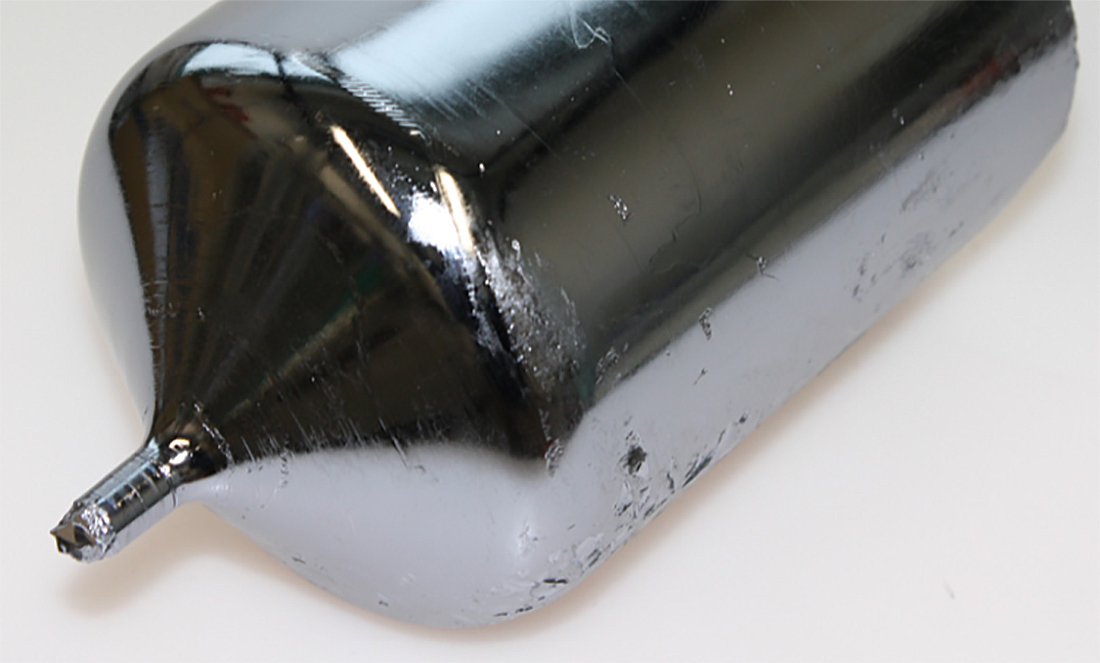

With a view to creating a more sensitive WIMP detector, Stephen has been studying a crystal called gallium arsenide (GaAs).

GaAs crystals glow when particles smash into them, and they glow more brightly if you include atoms of silicon and boron in the crystals. When altered in this way, GaAs crystals emit a detectable glow even in response to being bumped with low-energy subatomic particles.

Even better, there’s no afterglow.

And the clincher? Large and extremely pure GaAs crystals are commercially available.

Counting your dark matter chickens

“It’s hard to imagine a better material for searching [for dark matter particles] in this particular mass range,” says Stephen.

“I have tried to think of some way this detector material can fail and I can’t.”

Of course, a new detector material requires a new detector. Stephen would like to see several new WIMP detectors developed, including one that uses GaAs to search for signs of lighter dark matter.

He’s hopeful such a detector could uncover the first physical evidence of dark matter, but he’s not counting his chickens just yet.

“It’s a privilege to be working on such an important problem in physics, but the celebration will have to wait until clear signals are seen,” Stephen says.

“It’s possible that dark matter particles are even lighter than what we can see with GaAs, and their discovery will have to wait for even more sensitive experiments.”