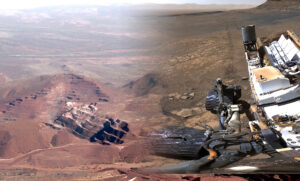

NASA’s Perseverance rover launched last week, on a mission to collect the first samples of Mars to return to Earth. To pull that off, they’ll have to nail a precision landing on autopilot – and then figure out how to pull off an even more delicate take off.

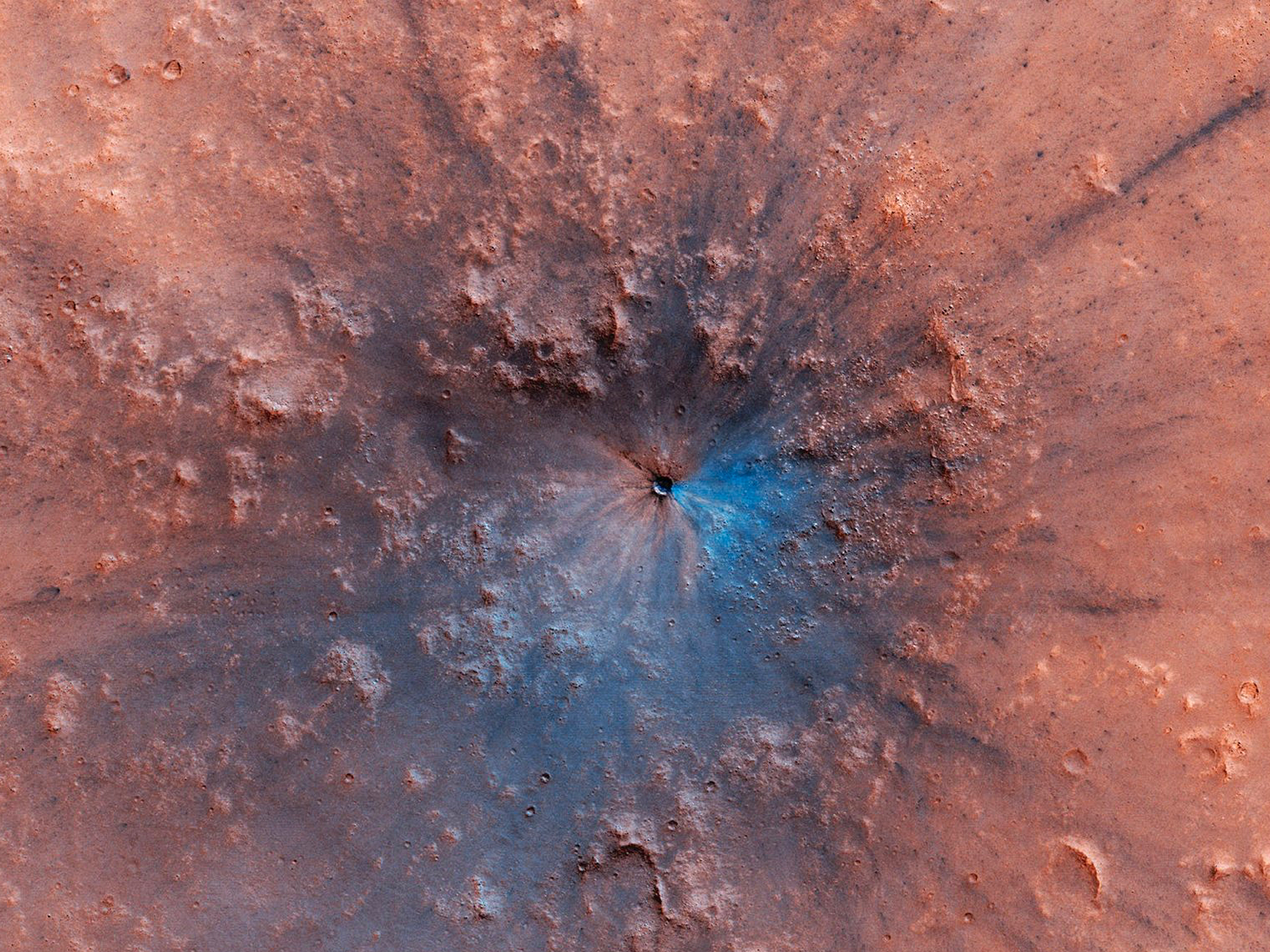

But spacecraft aren’t the only thing landing on the surface of Mars. It’s also regularly smashed by rocks from outer space – and those landings, while much messier, can tell us just as much about what Mars is really like.

Moving Mars

Andrea Rajšic is PhD candidate at Curtin, trying to help NASA detect meteorite impacts on Mars using seismometers on the InSight lander.

“We expected that a lot of seismic events will be caused by meteorites, by bombardment,” says Andrea.

When something hits Mars’ surface, they figured, the impact should show up on the lander’s earthquake – or Marsquake – detectors. To be detected, the impact has to be big enough, and close enough to the lander.

So far, they’ve detected nothing – not even an impact from last year that was just 40km away. It seems like Mars’s surface is a better shock-absorber than anyone thought.

“That also helped us to understand more about Mars – because it’s different to what we predicted based on the Earth and the Moon,” says Andrea.

Date a crater

But fresh impacts aren’t the only ones that can teach us more about Mars.

“In planetary sciences, we estimate the age of the surface by looking at how many craters it has. So basically, the more craters we have, the older the crust is,” says Andrea.

Here on Earth, forces like wind, volcanoes, earthquakes, and slow movement of the tectonic plates tend to erase all but the biggest craters. On Mars, scientists are realising, all those processes still happen.

“Mars is not actually as dead as people previously thought,” says Andrea.

But Mars has a thinner atmosphere, less gravity pulling things down, and less seismic activity. That means those craters stick around longer – and this lets scientists date different parts of of the planet.

“So we know, for example, that southeastern part of Mars is older than the northern plains, because it’s got more craters,” says Andrea

“But is this dichotomy due to tectonics or not? We don’t know. So there are many open questions still about the geology of Mars.”

Free samples

Craters are also responsible for bringing us our only samples of Martian rocks.

A big enough impact can blast tiny bits of Mars all the way out into space and back down to Earth. Once they’re here, they form part of the puzzle too.

Some team members find and collect those Martian meteorites. Others, like Ravi Patel, analyse those rocks to see what they’re made of. Once they know that, they can start to retrace its journey across the solar system.

“What Ravi detects in a rock, our colleagues try to see in spectral images so they can figure out where that rock came from on Mars,” says Andrea.

One planet, two planet, red planet, blue planet

It’s lot of detective work to do from a long way away. As always though, it can teach us a lot about our own planet. Earth and Mars formed in the same solar system, from the same material. Just like siblings, what happens to one can tell you a lot about what happens to the other.

“We usually think of Mars as Earth, but in the far future. So what is currently happening on Mars is probably going to happen to Earth,” says Andrea.

“Some processes that we cannot understand on Earth currently might be just because we don’t understand what’s happened on Mars.”