Have you ever had astronaut ice cream? The crunchy, space-themed treat is often sold with an astronaut on the packet. It lasts for years and won’t melt at room temperature. But despite its name and history, the one place you will never find astronaut ice cream is on a space station.

To understand why astronaut ice cream exists, you first need to know a little about what space food was like for early astronauts.

Early space food

The first few space flights were a nerve-wracking experience. Nobody really knew what zero gravity would be like for humans.

NASA wasn’t sure if food digestion was possible without the aid of gravity or what food would be safe for astronauts to eat in space. Loose food wouldn’t just fall to the floor like it does on Earth. Crumbs might float into the ship’s sensitive electronics, threatening the lives of everyone on board.

US astronaut John Glenn became the first person to eat in space when he snacked on a tube of applesauce on the Friendship 7 flight in 1962.

But applesauce wasn’t very filling, and without decent food, astronauts lost weight on spaceflights. NASA wanted to solve this problem by getting real food into space.

This meant taking traditional meals and finding a way to dehydrate, freeze-dry or heat-treat them to allow for storage. On the earliest missions, refrigerators were too power-intensive to run in space, so the food had to be storable at room temperature.

So NASA contracted the Whirlpool Corporation to figure out a way to store ice cream at room temperature.

When ice cream melts, the air trapped inside escapes. Whirlpool engineers invented a way to remove the water from ice cream without melting it. First, the ice cream is cooled to below -15°C, then a vacuum pump evaporates the ice using pressure while still keeping the ice cream cold. This stops the ice melting before it evaporates.

Earthbound, Neapolitan town

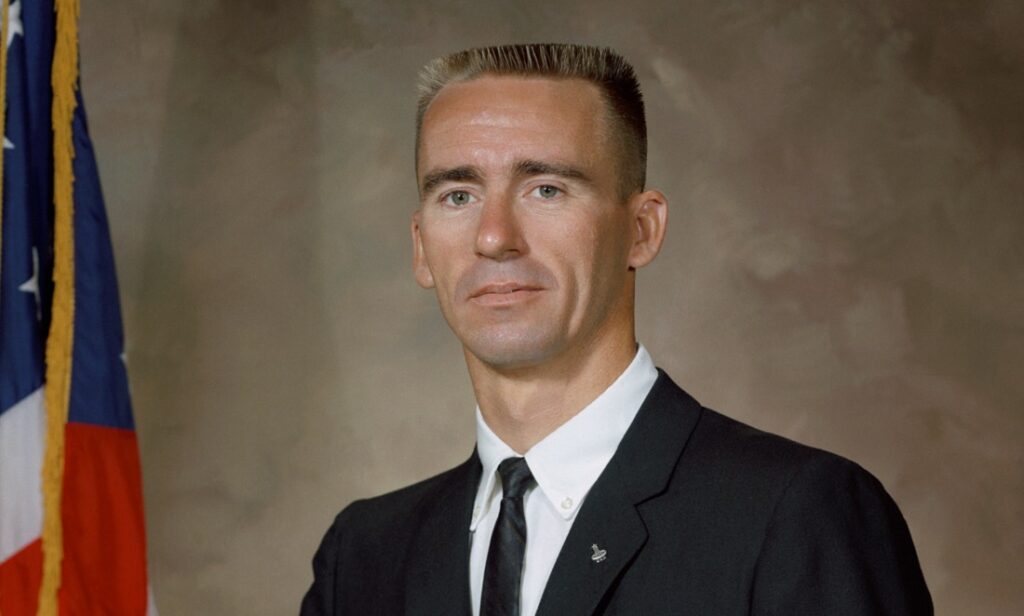

Despite being made for space, astronaut ice cream never quite made it off the planet. For a long time, people thought it had, because the NASA spaceflight media release reported it included on Apollo 7. It was this release that ensured the specially freeze-dried ice cream would forever be called astronaut ice cream.

But the last surviving member of the Apollo 7 crew, Walter Cunningham, denied there was astronaut ice cream aboard the flight.

There’s also no mention of the ice cream in the ship’s transcripts. In fact, due to the ice cream’s crumbly nature, it would have been incredibly dangerous aboard a spaceship.

And if it wasn’t aboard Apollo 7, astronaut ice cream has never been to space. No other flight has taken it. So astronaut ice cream isn’t really for astronauts.

As for what the astronauts do eat? Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were able to snack on some bacon cubes and fruit drink while on the Moon, and the menu has expanded since then. The International Space Station has meals ranging from shrimp cocktails to tortillas and even the occasional pizza night.